How Platforms Skirted the Spotlight — and Stumbled — in the 2024 Election

Issie Lapowsky / Nov 21, 2024After being battered for the foreign election interference of 2016 and the widespread election denials of 2020, Big Tech giants like Meta and Google tried their hardest not to become the story in 2024. And, to some extent, they succeeded.

As post-mortems about President-elect Donald Trump’s victory continue to roll out, detailing what went right and wrong for both parties, the role digital platforms played in the race has taken a backseat to broader finger-pointing (and fist-pumping) about the changing relationship between race and party affiliation, the sway of the manosphere, and the growing educational and political divide in America.

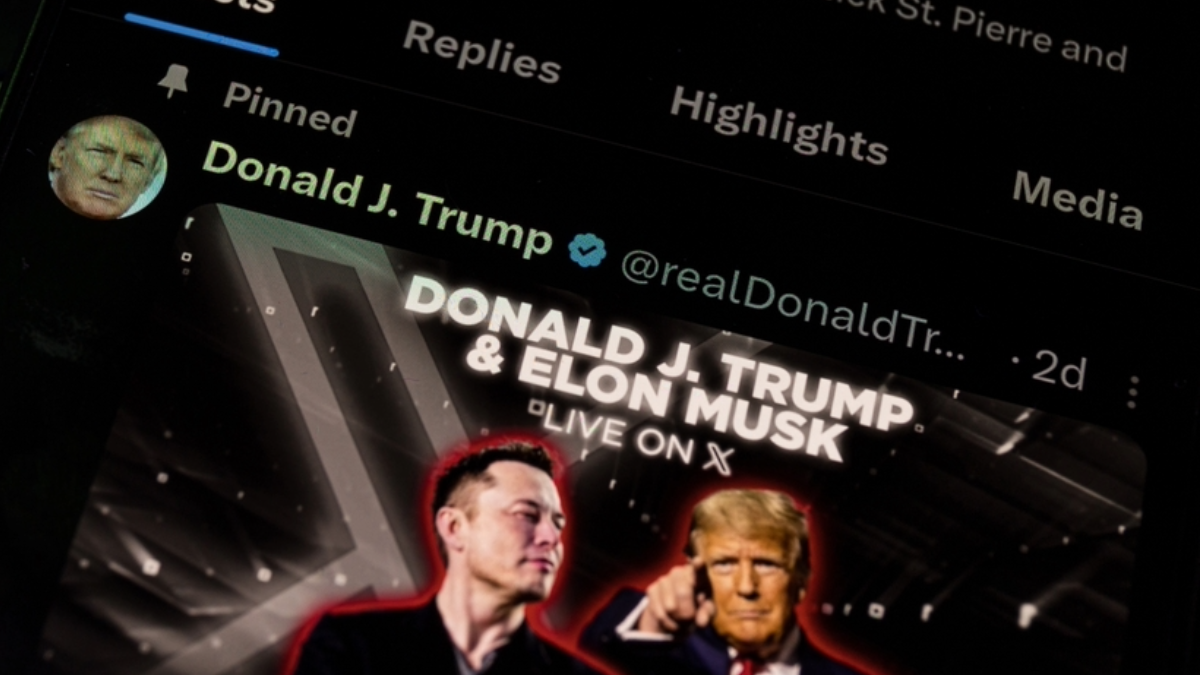

But just because tech platforms managed to stay above the political fray doesn’t mean all went smoothly. Policy changes allowed past election lies to fester on YouTube. Bans on political ads proved porous on TikTok. Deceptive and outright scammy ads fell through Meta’s cracks, and even its attempt to reduce the spread of political content wound up tanking the reach of credible news sources. And that’s to say nothing of X’s radical transformation into a right-wing echo chamber under Elon Musk.

Here’s a look at just some of the issues platforms faced this cycle and what, if anything, could have been done to avoid them.

AI-generated scams

In October, ProPublica, Tech Transparency Project, and Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism uncovered eight separate deceptive ad networks operating on Meta’s platform, which had run more than 160,000 election ads that were viewed more than 900 million times. At least some of the ads included AI-generated audio of former President Trump and President Biden hawking phony free cash giveaways in exchange for people’s personal information.

The ads were a clear violation of Meta’s newly implemented policies requiring disclosures of AI-generated media in political ads. They also broke the company’s outright ban on promising financial benefits to bait people into divulging sensitive information. But while Meta had removed a subset of those ads, more than half remained up and running at the time of the investigation.

It would, of course, be unrealistic to expect that Meta, a company that has published more than 17 million political and social issue ads since May of 2018, could ever have a spotless record. But, as ProPublica pointed out, the company’s political ad disclaimers are more lax than its closest competitor, Google’s, allowing political advertisers to use the names of their Facebook pages in public disclosures. In a statement to ProPublica at the time, Meta said it welcomed the investigation and that it continues to “update our enforcement systems to respond to evolving scammer behavior.”

One reason why this kind of discrepancy in public reporting is possible is because all of the political ad archives hosted by tech platforms are voluntary. A Senate bill called The Honest Ads Act, which was first introduced in 2017, would have mandated these disclosures and required political advertisers to disclose their contact information. But despite some bipartisan support and backing from the tech industry, that legislation has never moved.

Election denial

One major change from 2020 was the approach platforms took to election denialism in 2024. Meta, for one, got rid of its policy prohibiting political ads that claim the 2020 election was stolen. X restored political advertising on the platform, with very few restrictions in place. And Google lifted its ban on organic posts that denied the 2020 election results (though making unreliable claims about election results in ads is still prohibited).

According to one report by Media Matters for America, YouTube’s new policy for organic posts resulted in the most popular election misinformation spreaders on YouTube posting hundreds of videos containing misinformation about past and upcoming elections. In a statement about the report, a YouTube spokesperson told The New York Times at the time, “The ability to openly debate political ideas, even those that are controversial, is an important value — especially in the midst of election season.”

Researchers at The Institute for Strategic Dialogue, meanwhile, identified hundreds of ads regarding purported election fraud on Meta’s platforms. While not all of them violated Meta’s policies, many appeared to, including ads that claimed noncitizens were “poised to steal the 2024 elections” in Arizona. This is despite Meta’s policy against ads that “call into question the legitimacy of an upcoming or ongoing election.” It was much the same story on X, where the researchers found ads claiming Democratic poll workers in battleground states “BLATANTLY changed ballots from Trump to Biden.” While X has loosened its political advertising rules, it does prohibit ads that include “false or misleading information intended to undermine public confidence in an election.” X did not respond to Tech Policy Press’s request for comment.

Evasion of political ad bans

TikTok has prohibited political ads on its platform for years. But when the nonprofit group Global Witness ran a test to see whether the platform would accept ads claiming voters needed to pass an English proficiency test and calling for a repeat of the Jan. 6 riot, it found that TikTok approved four of the eight test ads. (Global Witness removed the ads before they ran). TikTok acknowledged at the time that the ads violated its policies and told Fortune that they “were incorrectly approved during the first stage of moderation.”

But it’s not just TikTok’s ad platform that posed a challenge. The company also struggled to enforce its ban with the millions of influencers who political organizations and campaigns are increasingly eager to pay for sponsored posts. One NBC News investigation unearthed more than 50 organic political videos on TikTok that were labeled as advertisements, some of which TikTok later removed.

Downranking politics and news

After the last eight years, it’s hard to fault Meta’s leadership for believing that it needed to, as Mark Zuckerberg has described it, “turn down the temperature” of political discourse online. The company announced shortly after the 2020 election that it would begin reducing the amount of political content in Facebook News Feed. It’s since doubled down on that promise, limiting political content on Instagram and Threads (though users have the option to change those settings).

But even Meta’s attempt to withdraw from this election had its own impact on the election, perhaps most notably by tanking traffic to news organizations sharing credible information about the election. This change arguably helped nudge voters toward alternative sources, most notably, podcasters and influencers on other platforms, for information.

Zuckerberg has cast this transition away from political content as a response to what users want, and there’s likely some truth to that. A recent Reuters Institute survey showed 40% of people admit to often or sometimes avoiding the news. News avoidance has already been growing steadily for years. But Meta’s moves have just made it a lot easier.

Related reading

Authors