How Google Manipulated Digital Ad Prices and Hurt Publishers, Per DOJ

Karina Montoya / Feb 2, 2023Karina Montoya is a journalist with a background in business, finance, and technology reporting for U.S. and South American media. She researches and reports on broad media competition issues and data privacy at the Center for Journalism & Liberty, a program of the Open Markets Institute, in Washington, D.C.

Last week, the Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division, joined by eight states, sued Google over illegal monopolization of digital advertising technologies, known as “ad tech.” In a historical move by the antitrust enforcer, the suit seeks to break up the giant’s dominance over this industry by having Google divest its ad server platform for publishers, Google Ad Manager, as well as its ad exchange, AdX.

DOJ’s complaint is lengthy and dense, but it attempts to throw open the black box powering the digital ads we see every day, which – while ubiquitous – we are likely to give little thought. This myriad of servers and platforms are the backbone that connects publishers and advertisers in the $270-billion U.S. digital advertising market, where Google controls most of the tools to sell, buy, and load online ads.

Given this market is invisible to users, it is hard to see what is at stake in this lawsuit. But as we read through DOJ’s allegations, a first clue emerges: the financial future of publishers. DOJ shows how, due to Google’s ability to manipulate ad prices, publishers ended up at the mercy of a monopoly that once promised them prosperity in their transition to the web.

Three Google programs, “Bernanke,” “Bell,” and “Poirot,” are described in the suit. To understand them, it is first necessary to review how the ad tech industry works.

How Digital Ads Are Placed

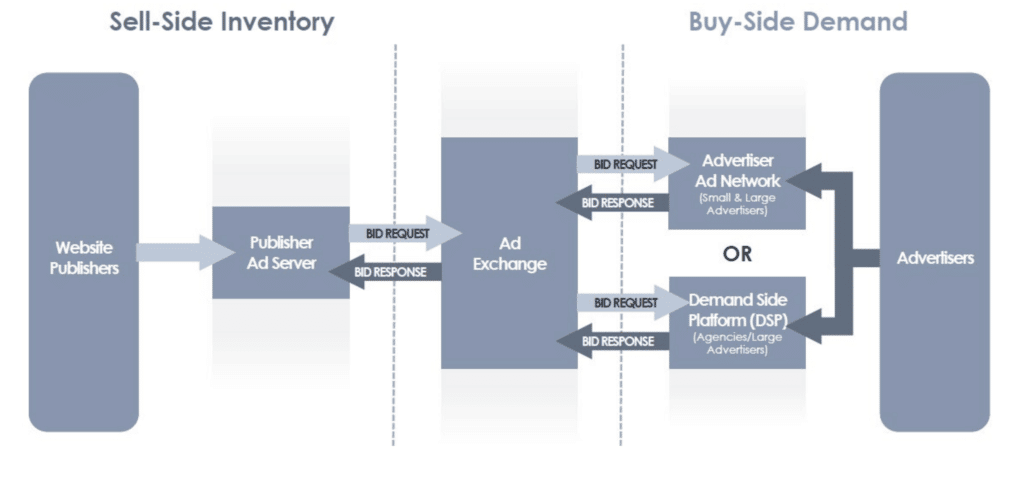

For ads to be placed, publishers and advertisers use three main ad tech products — which are also the focus of DOJ’s complaint: publisher ad servers (for publishers to manage their ad spaces), ad buying tools (for small and large advertisers to buy ads), and ad exchanges, where supply and demand meet.

Ad sales occur through auctions. When a webpage loads, a publisher ad server requests a bid for a number of ad views (impressions) to an ad buying tool. But it’s not a direct connection. The ad exchange receives the bid request, makes it “more appealing” (adding data such as a user’s location or browsing history), sends it to the ad buying tool, receives bid prices, determines the winner, and executes the sale on the publisher ad server. Finally, the ad is shown, all in a split second.

ad tech tools used in online digital advertising." Source

Google owns the largest ad exchange in the market, AdX. And it also owns the publisher ad server called Google Ad Manager — which resulted from the acquisition of DoubleClick in 2007 — and two ad buying tools, DV360 (which serves large advertisers) and Google Ads (for smaller advertisers).

For each ad dollar spent, the ad buying tools and the exchange collect fees, which vary upon the bid price. The publisher ad server also collects a fee, but it typically does not vary. In total, Google keeps at least 35 percent of every ad dollar spent, and Google’s AdX has maintained an undisturbed 20 percent fee since 2009, while rivals charge a fraction of that amount, according to DOJ. Google’s advertising revenues — including YouTube Ads — make up a sizable 80 percent of the giant’s total revenues.

Project Bernanke

Until late 2019, AdX executed ad sales through what is known as a second-price auction. This means that between two of the highest bids, where one is $1 and another 90 cents, the winner will pay only 91 cents – one cent above the second-highest bid. In essence, the second-highest bid serves to drive the final price of the auction upwards or downwards.

This incentivized ad buying tools to submit one bid per auction to AdX, to avoid driving up the ad price. But Google Ads allegedly submitted two bid prices, unbeknownst to advertisers and publishers, effectively controlling the winning bids and the price floors. To entrench its market power even further, the suit argues Google started manipulating ad prices under a different method, which it dubbed “Bernanke.”

featuring a screenshot of then-Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke. Source

Starting in 2013, according to the suit, Google Ads would submit bid prices to AdX above the amount advertisers had budgeted, in order to win high-value impressions for a group of publishers — the ones most likely to switch ad tech platforms. This insight could only be obtained by leveraging data in Google’s own publisher ad server. Once AdX cleared the bids, Google Ads would offset the losses by charging higher fees to other publishers less likely to switch ad tech providers.

This scheme allegedly helped Google lock in key publishers away from other ad exchanges and ad buying tools, all while maintaining its profits at the expense of other smaller publishers.

Project Bell

Technically, publishers in an auction — regardless of the ad servers they use — can choose whether or not they want AdX to buy ad spaces from them before other ad exchanges. But Google appears to have turned this choice into an obligation. With “Project Bell,” Google allegedly penalized publishers that did not give preferential access to AdX’s buyers, including Google Ads, by paying those publishers less revenues once an ad was placed.

For example, “if publishers tried to use a rival source of advertising demand for ‘first-look’ access to inventory, Google reduced bids by about 20 percent,” the lawsuit reads. This was Google’s scheme to protect AdX from other competitors having access to the same data about publishers that Google Ads had. In practical terms, if you were a web publisher and were growing in traffic, that scale wouldn’t matter to get a good deal on an ad sale. What mattered was who you were partnering with to make that sale.

In a previous complaint led by the Texas Attorney General over similar monopolization charges, “Bell” and “Bernanke” are also mentioned, but DOJ’s complaint provides a far more complete context.

Project Poirot

This program was launched in 2017 as a way for Google to fend off competition from a new auction technology called header bidding, which the complaint suggests executives at the company saw as an “existential threat.” “Poirot” is also part of the Texas AG complaint, but the DOJ makes the case that this scheme should be a part of Google’s anti-competitive actions to thwart header bidding.

To simplify matters, header bidding emerged around 2013 as a new way for publishers to obtain bid prices from multiple ad exchanges-- not just from AdX, since it was believed to be prone to manipulation. Such rival ad exchanges connected with large advertisers, most of whom used Google’s ad buying tool, DV360. By 2017, DV360 was the top buyer on every other ad exchange, which meant that a big portion of publisher header bidding revenue was coming from Google’s large advertising clients.

To stop this, DOJ says Google redirected the DV360 demand to AdX, to the detriment of other ad exchanges that used header bidding.

Poirot was an algorithm that allegedly detected rival ad exchanges engaging with the header bidding technology. That way, DV360’s bid prices would consistently be below the advertisers’ budgets on those exchanges. When the publisher ad server received the bid back, it used it as a reference to ask for more bids on AdX. Because DV360 also trades on AdX and knows what the advertiser’s budget is for that particular ad sale, it would now bid the maximum allowed budget, effectively taking a win away from header bidding.

This scheme shifted about $200 million of DV360 advertiser spend away from rival ad exchanges and toward Google, the DOJ states. Eventually, this reduced the competitiveness of header bidding and the benefits it had brought to publishers.

Time for a Reckoning?

All of the above claims will have to be contested in court. As expected, Google quickly responded to DOJ’s allegations, focusing on the many other players that operate multiple ad tech platforms as well. But if anything, DOJ’s findings would appear to crack open a Pandora’s box of conflicts of interest throughout the entire industry. In Europe, for example, similar observations were made by a panel of experts, which supported including new transparency obligations for ad tech in the Digital Markets Act.

Unsurprisingly, Google’s communications never mention nor contest the massive market shares it holds in each segment of this market: measured by revenue or ad impressions placed, Google Manager’s share of the publisher ad server market is 90 percent, AdX’s share of the ad exchange market is 50 percent, and Google Ads dominance of the ad buying tools market stands at 80 percent. These are the real figures to keep in mind when thinking of Google’s power over the financial future of web publishers.

It will take at least a couple of years to see this complaint move forward to trial, judging by how long it has taken another DOJ case against Google, regarding monopolization of online search, to show signs that it may go to trial this year. For now, we can see how the case questions the benefits of extreme consolidation in online services, which goes well beyond digital ads. If read through a privacy lens, the case even shows the high value of personal data obtained in real-time for programmatic ads to exist. The implications of a win by DOJ would be, to say the least, transformative for the entire web.

Authors