How Augmentation-Washing Hides Labor Automation

Sarah E. Fox, Samantha Shorey / Dec 22, 2025

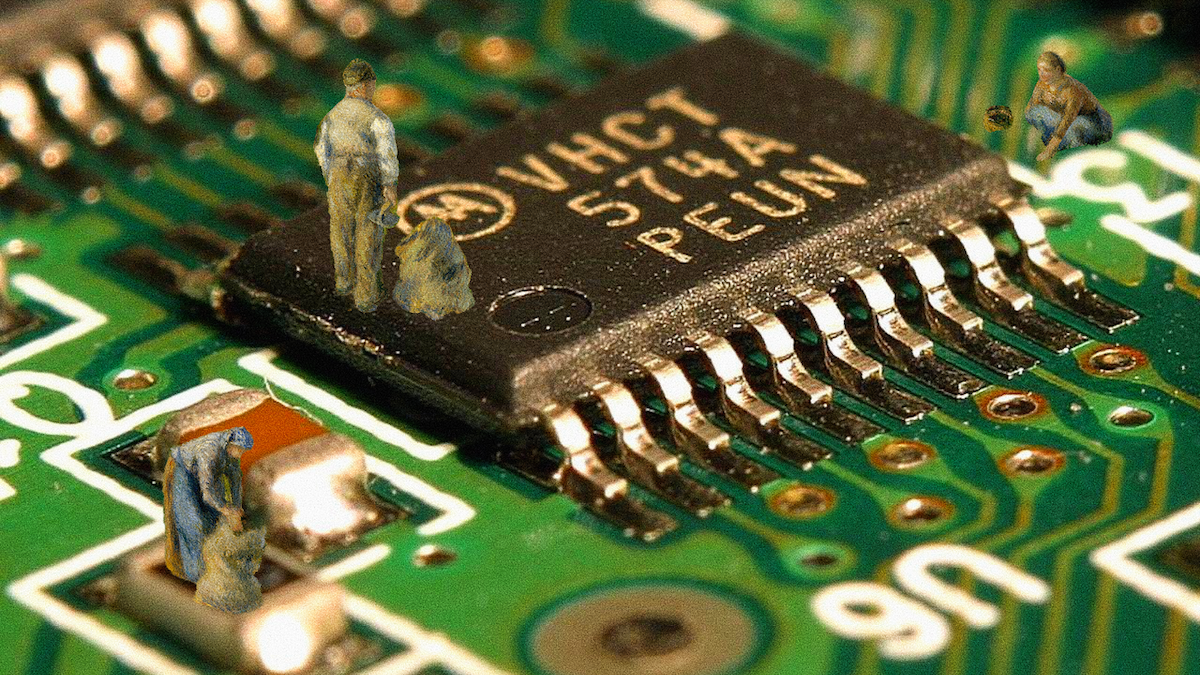

Elise Racine, Occupational Circularity, CC-BY 4.0

Recent reporting by The New York Times reveals that one of the nation's largest employers, Amazon, has mapped out plans to automate 75 percent of its US warehouse and logistics operations—a transformation (if left unchallenged) that could avoid the hiring of as many as 600,000 workers by 2033 or eliminate their roles outright. But, close readers will notice that Amazon doesn’t frame this change as one of replacement but rather collaboration. The internal documents obtained by the Times show that Amazon has deliberately sought to avoid terms like “automation” and “AI” — and has swapped the term “robot” for the portmanteau “cobot” (or “collaborative robot”).

Across sectors, the gap between corporate narratives of partnership and workers’ experiences is widening. Many so-called “cobots” reorganize labor around machine limitations rather than augmenting human capabilities. Workers take on unaccounted for, technically complex tasks while simultaneously trying to meet new expectations of AI-powered productivity — ultimately increasing their physical, cognitive and emotional load. Machines marketed as supplementing or even supplanting human effort routinely shift coordination burdens, unpredictability, and new forms of oversight onto workers themselves. They spend their time monitoring robots, intervening when they fail, and adjusting to machine-dictated rhythms. With the diffusion of genAI, workers across intellectual and creative industries are similarly being made responsible for AI outputs.

In the field of robotics, the term “cobot” emerged in the 1990s to describe machines designed specifically to work with human operators, sharing tasks, preserving human agency, and enhancing human skill rather than replacing it. Patent analyses now reveal that many supposed collaborative systems are engineered so that humans become appendages of machines. Workers stand by to monitor flow, clear jams, guide fragile automation, and intervene when the machine fails. Anyone who has used a self-checkout machine has personally experienced this dynamic.

Rather than the machine supporting the human, the humans (both employees and shoppers) end up supporting the machine. Executives at Amazon, for example, proudly discussed the creation of new jobs for technicians, who are also known across the industry as “robot wranglers” as they’re tasked with corralling and correcting wayward machines. The risk is that the cobot label becomes a rhetorical gloss concealing intensified speed, reduced autonomy, and the privileging of machine logic over worker agency. This is not exactly surprising, coming from a company known for a “bruising” workplace culture at every level. Yet our own ethnographic research in waste industries shows how widespread this strategy has become.

The gap between rhetoric and reality can be conceptualized as “augmentation washing.” Just as green-washing obscures environmental harm with friendly branding, augmentation-washing uses the language of empowerment, collaboration, and shared control to sanitize deeper changes to labor relations. In public materials, Amazon and similar firms emphasize that their robotics and AI systems “work alongside” employees to create safer, more productive workplaces. For instance, Amazon’s chief technologist, Tye Brady, described robots as designed to “amplify what our employees can do.”

Yet, according to reporting from The New York Times, the company’s internal documents suggest that the goal is to avoid hiring by redesigning the worker-machine interface such that machines absorb as many tasks as possible, leaving humans to handle the exceptions, edge cases, and troubleshooting. It is not empowering in the sense of expanding worker agency, but instead it repurposes worker capacity to support machine throughput. The narrative of augmentation is a strategic misdirection: instead of offering a genuine human-machine partnership, it disguises a form of automation that relies on intensified human labor in support of machines.

Popular histories of computing characterize augmentation vs. automation as the great schism of computing research. In the 1960s, computer scientist and psychologist J. C. R. Licklider published “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” describing a future of interactive computing in which machines would make new forms of thinking available to humans. This vision rested on the premise that humans and machines should be partners, each amplifying the other. Yet, even then, Licklider observed a trend towards mechanical systems where “the men who remain are there more to help than to be helped.” Linklider later funded Douglas Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute—the birthplace of the computer mouse, hypertext, and other interactive computing tools—all of which embodied the idea that computers should magnify human capability.

By contrast, the AI-automation camp led by John McCarthy’s Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (also funded by Licklider)pursued the simulation of human capabilities like vision and speech within machines. Research at the laboratory pioneered the robotic arm that is the foundation of contemporary industrial assembly processes. Over time, industry standards gravitated toward the autonomous approach: machines built to emulate rather than enhance human efforts.

Early development of cobots by mechanical engineers at Northwestern University, Michael Peskin and J. Edward Colgate, exemplified an alternate ethos more in line with Licklider’s original vision. Their devices provided mechanical assistance to assembly line workers, who maintained direction over the machines. These systems emerged under the banner of augmentation, not automation—a position that recognized robots as amplifiers of human skill. The Wall Street Journal identified cobot as one of the keywords for the new millennium in their January 1, 2000 issue: “Cobot: noun. A collaborative robot designed to help workers on the job instead of replacing them.” Autoassembly is used as the illustrative example, where a robot “helps a human being” install a dashboard rather than conducting the task independently.

Today’s corporate use of cobots taps their enrichment narrative, yet deployment often aligns with the replacement logic. In practice, the human is no longer the augmented subject; the machine is. This restructuring has clear implications for manual labor but also for knowledge work. Copywriters, for example, have been laid off en masse due to AI. Instead of stable employment, they’ve been hired elsewhere in the industry as contract or gig workers to rewrite AI slop or rate AI outputs.

The policy challenge here is not just novel technology, but what “collaboration” will mean in the future of work. When the terms “coworker” or “cobot” are used, regulators and labor agencies must ask what those terms actually signify in practice. Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro’s administration has clarified that an AI system can never be personified as a worker or employee. If a machine cannot be a worker, calling it a “coworker” or “teammate” poses the same risk of obscuring real labor relations. Policy begins with transparent typologies: the “cobot” label should be tied to technologies with measurable benefits to workers that reduce pace, increase autonomy, improve safety, or support more meaningful activity.

If we are to reclaim the meaning of “collaborative robotics,” we have to begin where collaboration actually happens. Real collaboration is not created by marketing language; it emerges when workers have the power to shape how technology enters their workplaces. Before any “cobot” is designed or procured, workers and their unions should lead in task redesign, ergonomic evaluation, workflow planning, and impact assessment. Equally important is ongoing, enforceable worker feedback throughout deployment. Metrics should not center on throughput or uptime, but on worker autonomy, cognitive load, injury rates, and emotional stress. Evaluation criteria must ask a simple question: does the system expand what a worker can do, or merely expose them to new forms of risk?

Unions are increasingly bargaining directly over the deployment of AI and robotics. A landmark example is the agreement won by SEIU Local 688 with Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro, which secures strong protections around AI use in public-sector workplaces, including guardrails on surveillance, transparency requirements, commitments to worker training, and provisions ensuring AI augments rather than undermines workers’ roles. Similarly, the Transport Workers Union has negotiated contracts that give workers veto power over certain autonomous technologies, requiring employer consultation and union approval before automation can be introduced into safety-sensitive environments. These contracts also include strong job-security protections: bus operators and mechanics cannot be laid off or have their wages reduced because of new or modified technology. Together, these agreements show that worker power is not an afterthought but an essential precondition for genuine collaboration.

Without enforceable mechanisms — surveillance limits, transparency mandates, training guarantees, job protections, and even outright veto authority—claims of “collaboration” risk becoming another form of augmentation-washing rather than a pathway to shared benefits. Policy and organizational governance can build on these models. Whether in the public or private sector, employers introducing cobots should be required to demonstrate that they have documented benefits validated by workers themselves. Companies must also provide meaningful pathways into work with machines—not vague promises of “upskilling,” but enforceable commitments backed by training funds, redeployment guarantees, and negotiated labor-transition plans.

Ultimately, true collaboration begins with worker voice, not vendor promises.

Authors