Governments Are Using AI To Draft Legislation. What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Chris Stokel-Walker / Feb 10, 2026

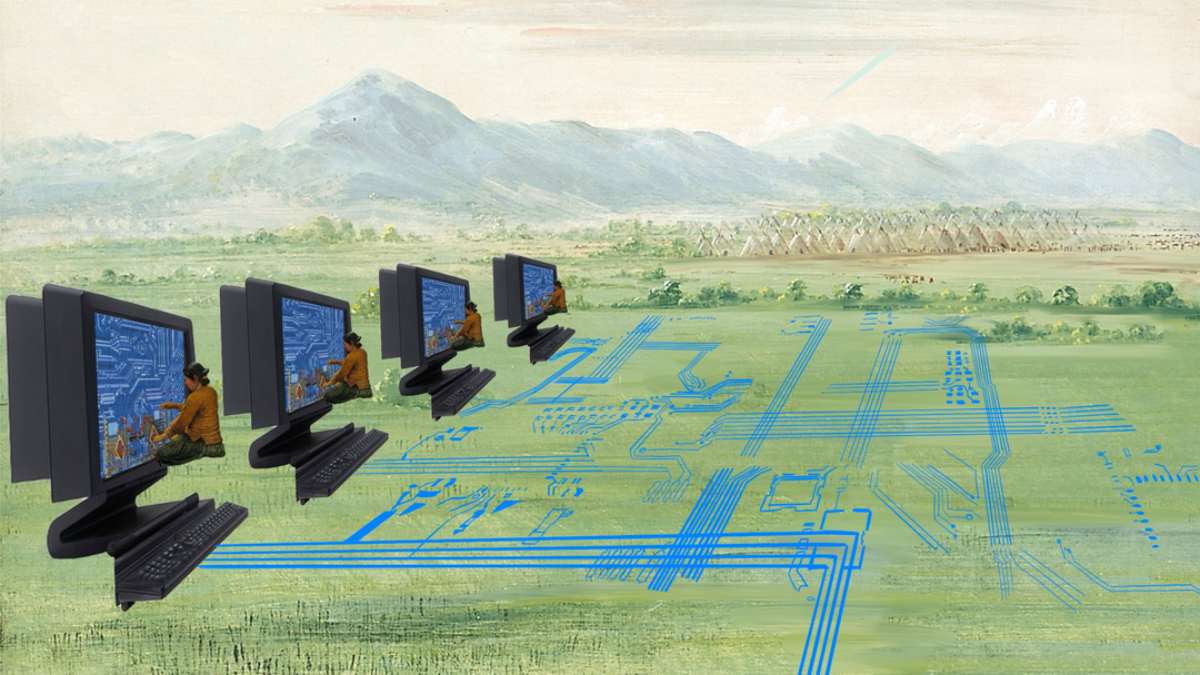

Weaving Wires 2 (Hanna Barakat & Archival Images of AI + AIxDESIGN / Better Images of AI)

When British officials reviewed evidence for an independent water-sector overhaul last year, they ran into a familiar civil-service problem: tens of thousands of submissions, all needing review — fast — before the window for reform closed. So ministers turned to an in-house AI tool called Consult, part of the “Humphrey” suite, which the UK government said sorted more than 50,000 responses into themes in around two hours. It cost £240, they claimed, followed by 22 hours of expert checks — a workload that, scaled up across government, could save 75,000 days of manual analysis each year.

A UK government spokesperson tells Tech Policy Press that “AI has the potential to transform how government works — saving time on routine administrative tasks and freeing up civil servants to focus on what matters most: delivering better public services for the British people.” They added that they’re ensuring its responsible use across government with guidelines and audits.

“Government services are easily flooded with requests,” says Chris Schmitz, a researcher at the Hertie School in Berlin. Having studied AI use across governments and politics, he argues the real challenge isn’t just analyzing consultation material, but preventing the process itself from being gamed.

“I think a really obvious way to stop flooding public participation is to just get every citizen to say one thing,” he says. Without that kind of guardrail, “public consent can be delegitimized by AI pretty quickly,” adding: “There’s already a tool to object to planning applications in the UK with AI.”

Governments worldwide are fighting AI with AI

The UK is far from alone in using AI in the legislative process. The Italian Senate has described using AI to help deal with amendment overload by clustering similar proposals, spotting overlaps, and flagging potential filibustering tactics so staff can compare the substance far quicker than by hand. And last week, the European Commission published a tender to supply multilingual chatbots that could help “users navigate legal obligations, definitions, and procedures” under the EU AI and Digital Services Acts.

The Italian Chamber of Deputies has backed a project called GENAI4LEX-B, which supports legislative research and drafting by summarising committee amendments and checking bills against drafting standards. In Brazil, the Chamber of Deputies is expanding its Ulysses program, which analyzes and classifies legislative material, rolling out an internal “Ulysses Chat” and even making it easier for staff to use external AI platforms such as Claude, Gemini and GPT. It’ll do so while promising strong security and transparency.

Other countries are using AI to support the workflow involved in drafting legislation. Last year, New Zealand’s Parliamentary Counsel Office, the body that drafts the country’s laws, tested a proof of concept that uses AI to generate first drafts of clause-by-clause explanatory notes, explicitly tied to concerns about data sovereignty and over-reliance.

Using the tech to try and explain the complicated language of legislation — and its consequences — is also being considered in Estonia, where Prime Minister Kristen Michal has publicly suggested parliament use AI to check bills, after a vibe-coded AI mistake finder by a member of the public flagged issues in draft legislation that allowed online casinos to duck their tax bills this year, costing the Estonian government some €2 million a month in lost tax revenues.

“I have encouraged the Estonian parliament to consider using artificial intelligence tools in the legislative process to avoid possible errors,” Prime Minister Michal tells Tech Policy Press. “This could be a smart and practical solution.” Michal admits that he uses AI on a regular basis, and “sees it as a powerful and promising tool — if we also keep our critical thinking. AI doesn’t replace people; it can empower them.”

Legislative legitimacy at scale

Michal thinks that AI can be a useful tool for spotting exploitable loopholes in legislation and closing them. But using AI to parse public consultation responses and drive legislative change could backfire: foreign states could skew outcomes by flooding government inboxes. The risk is a legislative DDoS — not hacking systems, but overwhelming them with plausible submissions, template amendments, or mass-generated objections that drown out genuine engagement.

That’s bad news for governments, because it cuts at legitimacy. In 11 out of the 28 countries surveyed in Edelman’s annual trust barometer, governments are more distrusted than trusted. Trust in AI is even weaker: an August 2025 survey of Brits found just 29% trust their government to use AI accurately and fairly.

In theory, tools like the UK’s Consult help officials sift and summarise public input, but once they are used for consequential decisions, the filtering method itself becomes part of the decision-making system, making transparency essential.

Ruth Fox, director of the Hansard Society, says public officials already recognize the risk of AI outputs becoming a default crutch. “They’re alive to the questions this raises about human validation,” she says. “You still need human eyes and a human brain to check that the themes and sentiment it produces are actually accurate.”

And where AI is used, Fox argues disclosure is vital. “There needs to be some kind of transparency and accountability about what will be declared when and how in the process.”

That’s because there is always the risk of something going wrong. Joanna Bryson, an AI ethicist at the Hertie School in Berlin, worries about AI models’ fragility: outages, sudden model changes, or vendor leverage can all change decisions if AI is central to the democratic process. The goal should be systems that can be audited and owned — “someone that can be held accountable who did what, when,” she says.

Vibe coding legislation in the United States

The US is being more upfront about its use of AI. The federal government plans to use Google’s Gemini to accelerate deregulation, including drafting supporting text for rulemaking, according to Department of Transportation attorney Daniel Cohen, as reported by ProPublica. But that’s not always a benefit.

Philip Wallach, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said he was shocked by how casually officials acknowledged using AI, warning that this could expose AI-assisted regulation to legal challenge. “If you don’t follow required procedures, a judge can strike the rule down as arbitrary and capricious.”

Wallach argues that governments can use AI, but they can’t use it as an excuse to cut corners. “I just think you can't lean so hard on this speed-quality trade-off to the speed side,” he says, because once AI-generated drafting gets embedded in a process, the errors are not always obvious, and the cost of getting it wrong can be huge at a governmental level.

For Schmitz, the worry is that governments treat AI integration as a set of small, technical fixes rather than a structural shift in how citizens can influence the state. Tools that triage, summarize and draft can feel like common-sense upgrades, but “these are patchwork solutions,” he says, warning that he doesn’t see “any particularly systematic consideration of what this means for the long-term legitimacy of public participation processes.”

AI use is not inherently negative, Schmitz says. It can modernize democratic processes. But if governments use it mainly to manage machine-generated input or save effort, they risk deepening the distrust they seek to curb. “The friction of [the public] interacting with them is rapidly dissipating,” says Schmitz. “This is a huge opportunity to win back a lot of trust, if designed for. But it could also be really, really bad for trust if it’s not.”

Authors