Google Ad Tech Trial Moves Forward But Without a Jury: What It Means for The Case

Karina Montoya / Jun 10, 2024Karina Montoya researches and reports on broad media competition issues and data privacy at the Center for Journalism & Liberty, a program of the Open Markets Institute, in Washington, D.C

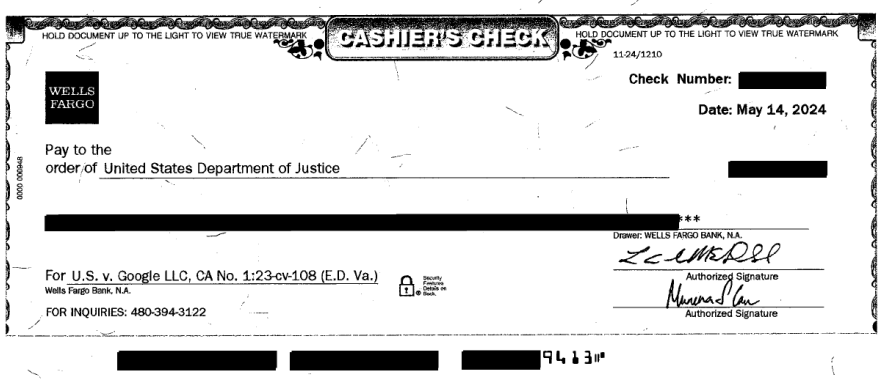

An illustration of Google cashier's check to the DOJ.

The Department of Justice antitrust case against Google’s monopoly over digital advertising technologies (ad tech) – which the DOJ argues hurt web publishers, advertisers, and the federal government – won’t go to a jury after all. Instead, Virginia federal Judge Leonie Brinkema will render a verdict in a bench trial, which is set to start on September 9.

In a hearing at the Alexandria federal court on Friday, the judge sided Google’s request to strike the DOJ jury demand, indicating she was satisfied with Google’s payment for damages to federal agencies. During the hearing, it was revealed the cashier’s check Google tendered to the DOJ in May to avoid the jury trial was a little over $750,000, which after trebling and interest would amount to $2.3 million.

The judge will post a ruling with a more detailed explanation of her decision in the upcoming days. But in sum, the judge concluded that the back and forth between Google and the DOJ about the methodology for calculating damages– using different “but for” scenarios where Google would have not had monopoly power – would undermine the right of the jury to make determinations based on complete and accurate information.

The DOJ claimed Google’s damages to federal agencies would likely have been well over $1 million, with calculations based on a scenario of a highly competitive ad tech market. If so, after trebling and interest, the final payment would be much higher than $2.3 million.

DOJ lawyers also argued the judge should ponder whether a jury could conclude the same based on evidence the DOJ would show in the trial. But Judge Brinkema thought otherwise. “The government has no interest in recovering damages,” she said. “The real issue here is to stop the anticompetitive behavior […] to get injunctive relief.”

What Now?

Although damages to the federal government are now settled, the hearing made clear that Google will have to face the main allegations of the complaint, which involve a wide range of price manipulation schemes that overcharged advertisers and reduced payment to web publishers—mostly news publishers— as well as Google’s strategy to buy and kill other ad tech companies to secure its monopoly over digital advertising.

This would have been the first time Google would have had to disclose the inner workings of its ad tech business directly to the public. Now, access for the press to cover the trial becomes even more important. Seemingly aware of this, the judge emphasized that all exhibits admitted as evidence during the trial should be immediately available to the press and the public. She also instructed the parties to file ‘Findings of Facts’ and ‘Conclusions of Law,’ which will prove to be helpful in a case as complex as this, three weeks before the trial starts.

The core of the complaint does not stop at redressing monetary damages to federal agencies. It is expected that the issue of market definition and conflicts of interest arising from Google’s dominance in all segments of the ad tech market will take center stage, which would allow the DOJ to show evidence of harms to advertisers and publishers, and to make the case that structural separations are needed to restore real competition in the market.

How Google’s Cashier’s Check Did the Work

What brought Google and the DOJ to this hearing—scheduled only a week before it took place—goes back to a cashier’s check Google tendered to the DOJ in May. After consenting to a jury trial more than a year ago, on May 16 Google filed a motion to strike the DOJ’s demand for a jury trial, to which it attached a redacted cashier’s check.

Google cashier's check to the DOJ as shown on attachment #23 of its motion to avoid a jury trial.

The check was meant to cover the monetary value of damages the DOJ was seeking on behalf of federal agencies that bought ads using Google ad tech tools for about $100 million. Per the DOJ, Google had the ability to overcharge the agencies fees because it holds an illegal monopoly over the digital advertising market. With the check, Google sought to avoid a jury trial. Google also argued the case would be too complex for a jury to understand.

The DOJ indeed has the right to request a jury trial so long as civil damages to the federal government exist, because they translate into damages to the American people. If the monetary value of the damages was covered, the DOJ would lose its right to take the case to a jury. For its check, Google based its calculations on information presented by experts cited by the DOJ in emails exchanged with Google and in court filings.

In its response to Google, the DOJ conceded that precedent shows a request for a jury trial can indeed be struck if Google paid the government the full extent of its damages. But the DOJ continued to dispute the value Google was offering—which was redacted at the time. And so a new hearing was scheduled to solve this matter on Friday, June 7.

In the hearing, the DOJ noted that its experts’ calculations were always meant to show a highly conservative scenario in which Google would have faced competition, and that given Google’s “widespread and egregious” monopolistic behavior, the calculations “grossly understated the real damage.” But the judge determined the check covered the highest possible amount the DOJ had sought in its initial court filings.

The next key date for Google and the DOJ to meet again in court prior to September will be on June 21, which is the deadline for oral arguments at the summary judgment stage.

Authors