Global Internet Freedom Declines for 12th Straight Year, Says Freedom House

Justin Hendrix / Oct 19, 2022

This year, Freedom House– a nonprofit organization founded in 1941 to advance democracy and human rights– released a report on “The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule,” chronicling 16 years of aggregate decline in democracy across the world’s nations. “Countries in every region of the world have been captured by authoritarian rulers in recent years,” say its authors. “The leaders of China, Russia, and other dictatorships have succeeded in shifting global incentives, jeopardizing the consensus that democracy is the only viable path to prosperity and security, while encouraging more authoritarian approaches to governance.”

It is against this backdrop that Freedom House has now published its latest installment of Freedom on the Net, a report that analyzes trends in global internet freedom. Just as the macros trends do not favor democracy, nor do they favor a free and open internet. Rather, 2022 marks the 12th straight year of decline for global internet freedom, with sharp downgrades in countries including Russia, Myanmar, Sudan, and Libya.

“Authoritarian states are vying to propagate their model of digital control around the world,” write authors Adrian Shahbaz, Allie Funk and Kian Vesteinsson. “More than three-quarters of the world’s internet users now live in countries where authorities punish people for exercising their right to free expression online.”

Freedom House estimates that of the current human population on the planet:

69% live in countries where authorities deployed progovernment commentators to manipulate online discussions

64% live in countries where political, social or religious content was blocked online

64% live in countries where individuals have been attacked or killed for their online activities since June 2021

51% live in countries where access to social media platforms was temporarily or permanently restricted

44% live in countries where authorities disconnected internet or mobile networks, often for political reasons

China remains the most oppressive nation on the list; there, the “main internet regulator issued guidance requiring platforms to align their content moderation and recommendation systems with ‘Xi Jinping Thought’—the official ideology of the current CCP leader.” Things continue to go south in Russia, as the government spirals into a more authoritarian posture following the full scale invasion of Ukraine. India is still struggling, but showed marginal improvement on the prior year as civil society groups are challenging the government’s attempts to limit free expression in court. Globally, the internet continues to fragment, as governments erect barriers to expression and the flow of information and data across borders.

The United States showed “marginal” improvement on the list, but there are still challenges, not least among them the “mass denial of the outcome of the 2020 presidential election by former president Donald Trump and his supporters, driven in part by online conspiracy theories and disinformation” that “polluted the information environment and seeped into the broader American political system.” The U.S. has made more progress on matters of internet freedom abroad, say the authors, with a new Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy in the State Department and various initiatives, such as the Declaration for the Future of the Internet, launched by the Biden administration.

It isn’t all bad news

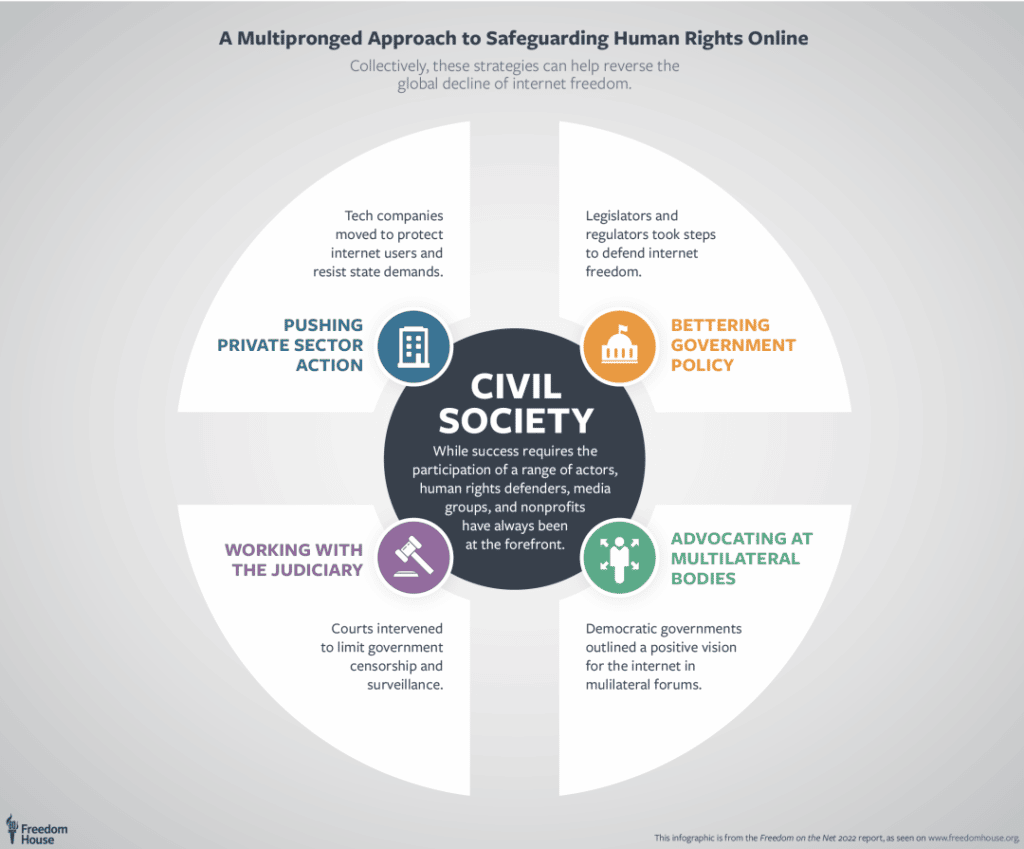

While the view from the moon would suggest a species engaged in a multiyear project of digital repression, on the ground there are bright spots. “Twenty-six countries experienced net improvements in internet freedom over the past year, the highest such figure since the inception of Freedom on the Net,” says the report. Where progress is being made, Freedom House analysts see patterns– tech companies taking action to “protect internet users and resist state demands,” legislators and regulators taking steps “to defend internet freedom,” courts intervening “to limit government censorship and surveillance,” and democratic governments asserting “a positive intervention for the internet in multilateral forums.”

Key to all of this is civil society groups defining problems, raising awareness and developing strategies to address it. Case studies for progress include The Gambia, which despite its “partly free” ranking on the index has seen a multi-year improvement, and in 2021 enacted a law that was developed “using a multistakeholder model, with Gambian and international civil society and the private sector providing input.” Under the administration of President Adama Barrow, “arrests and harassment of internet users for their online activity have steadily declined.”

The best performers on the overall index include Iceland, Estonia, Costa Rica, Canada and Taiwan. Only one of these countries faces a major existential threat– with more and more focus on the possibility that China may attempt to take Taiwan by force, “civil society, the technology sector, and the government have taken innovative action to counteract the impact of disinformation campaigns originating from China.”

Recommendations

The report includes recommendations for policymakers and for tech firms. For policymakers, the protection of privacy and security- including “robust encryption,” data privacy protections, and restrictions on censorship and surveillance technology are seen as key. To protect free expression, access to information, and the diversity of the online environment, the Freedom House authors assess nations must pay particular attention to access issues, “particularly during elections, protests and periods of conflict.” Governments should support “a resilient information space” by backing independent media, and should support security and “digital activism trainings, as well as “technologies that help individuals in closed environments circumvent government censorship, protect themselves against surveillance, and overcome restrictions on connectivity.” And legal and regulatory frameworks must be strengthened to “enshrine human rights principles, transparency and democratic oversight in laws that regulate online content.”

For companies, fairness and transparency in content moderation, standing up to government orders, engaging with civil society, and attempting to “enshrine human rights principles in product design and development” are key priorities set out by the authors. Data minimization is one tactic that would help, as would the suspension of sales of products found to violate human rights. Adherence to global human rights standards, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Global Network Initiative Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy, would ensure progress.

Will a turning point ever come on the overall trend towards repression and authoritarianism? The report suggests that there are certain “swing states” worth watching for the answer. These include Brazil and India, where democracy is as precarious as internet freedom. If the global trajectory is to look any different by 2023, progress in places like these may be crucial. It would be nice if the next installment of the report did not contain a section titled “Tracking the Global Decline.” Fingers crossed.

Authors