Germany’s Data Center Boom is Pushing the Power Grid to Its Limits

Sarah-Indra Jungblut / Nov 25, 2025As Europe pursues the vision of becoming an AI continent, the AI infrastructure boom in Germany is already exposing the limits of the energy supply and physical infrastructure. And the question remains: What price will society and consumers ultimately pay?

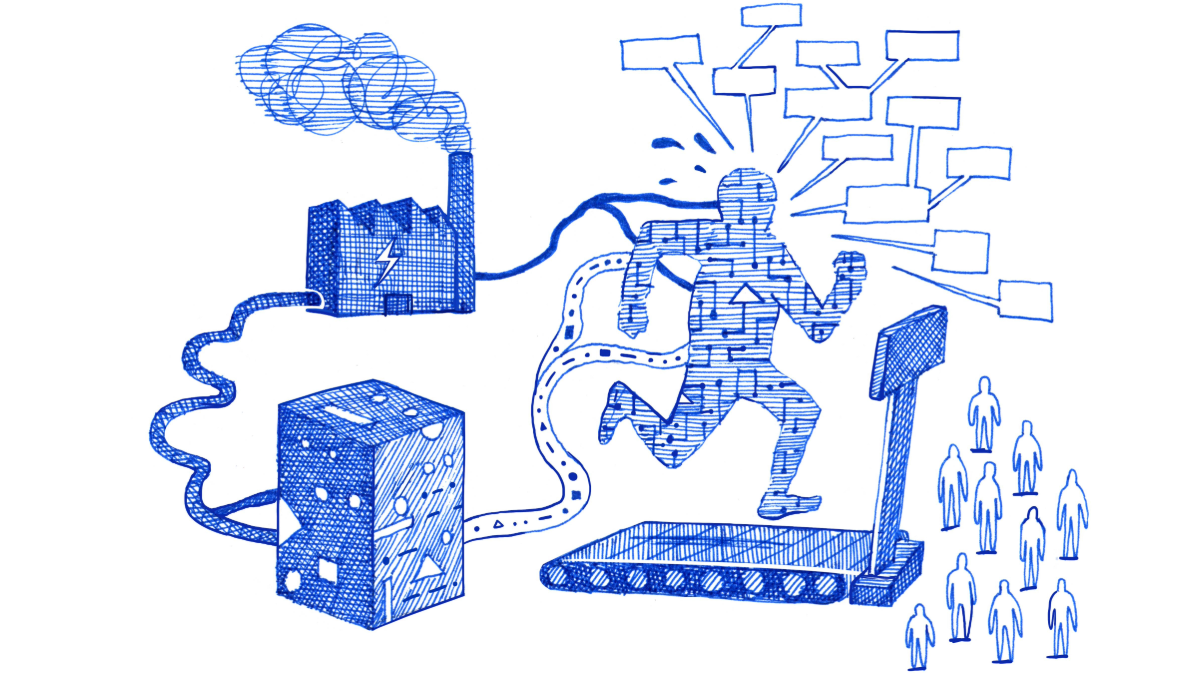

Credits: Juliette Baily, Kevin Lucbert for AlgorithmWatch CC BY 4.0

The fear of being left behind in the AI race is leading to a massive expansion of computing power worldwide. The expansion in the US is striking, but companies and governments in Europe are catching up with the construction of new large data centers on a massive scale. The EU has announced that it will mobilize hundreds of billions of euros “to make Europe an AI continent.”

Specifically, the Commission plans to expand 13 “AI factories” equipped with high-performance computers by the end of 2025, while also investing in the establishment of at least five “AI gigafactories.” These are on a whole new scale: With about 100,000 state-of-the-art AI chips, these new gigafactories will be four times as large as the existing factories. The objective of the EU is to at least triple the capacity of data centers in the next five to seven years.

However, while the industry itself, as well as policymakers, continues to stoke concerns that even the new capacities may not keep pace with demand, the data center boom is already presenting many regions with significant challenges. Energy consumption is rising dramatically, especially in the hotspots where the number of data centers is rapidly increasing.

Germany is already the European country with the most data centers: DataCenterMap lists around 490. More than 100 of them are located in the Frankfurt area alone. This makes the city home to the highest density of data centers in the country – and the ecological, social, and economic effects of this massive expansion are already evident. The grid connections are all allocated for the next few years, and the space available is already taken. If the AI boom continues unabated, the problems that are arising in Frankfurt could also be replicated in many other cities and regions – and it remains to be seen who will ultimately pay the price for the expansion of data centers.

Obtaining data on data centers’ performance is not easy. The sector is highly opaque: Large companies operating internationally that also process and host data in Germany keep their figures as closely held trade secrets.

Since 2010, the capacity of data centers and smaller IT installations in Germany has more than doubled, and the market is expected to continue growing. Industry associations such as Bitkom and the German Data Association (GDA) predict the doubling of IT capacities by 2030. Moreover, there is a trend towards the construction of larger data centers exceeding 100 MW. To put that into perspective, a wind turbine installed today has a capacity of 5 MW.

As a result, data centers and smaller IT installations account for approximately four percent of gross power consumption in Germany in 2024. According to the demand assessment by the Federal Network Agency, this figure could rise to ten percent by 2037.

Is there a risk of Germany ending up in the same situation as the USA and other hotspots? Even though the pace of expansion and the size of data centers are not comparable to those in the US, their impact on the energy market is already remarkable.

In Frankfurt, the power grid has reached its limit

At the time of writing this article, DataCenterMap reports that 126 data centers are located only in Frankfurt. According to the city government, another 12 have already been approved.

They are drawn there by DE-CIX, which claims to be the biggest internet exchange operator in the world. The exchange makes the city particularly attractive for providers of computing power and storage space, as it allows data to be transmitted almost in real time.

As a result, data centers have now become the leading source of electricity consumption in Frankfurt, accounting for up to 40 percent of the city’s total power demand –and the local energy supply is being pushed to its limits.

Demand already exceeds the electricity capacity available in the network area of Mainova subsidiary NRM. The number of short-term requests from data center operators for large grid connection capacities is still rising sharply, according to Mainova (even though they are already quite high). “The NRM, as the responsible distribution grid operator, receives an average of 5 to 10 qualified service requests from data center operators per year,” Mainova reports. The requested connection services would be between 50 and 100 MW, “presumably with an upward trend.” But for now, it seems that there are no new developments in terms of power technology in Germany’s financial capital. “Until 2030, new, larger projects will actually have no chance of being connected to the grid,” said Kilian Wagner. Mainova predicts an even longer timeframe: “Currently, it can be assumed that new high-performance connections will only become available again in the mid-2030s.”

All companies that require a large power grid are affected, as the network operators must treat all customers equally. As the responsible distribution network operator, NRM has been using the pro rata method for contract awarding since 2020. This means that all applicants who require a high-performance connection to the grid with more than 3.5 MW must register their expected power consumption with the network operator as part of the application process. At the end of the annual application process, the available capacities will then be distributed to the applicants, “transparently and without discrimination,” according to the network operator’s own statements.

In fact, the data center operators have already secured all available power capacities in Frankfurt, according to Max Kendl, Spokesperson for City Development at the Chamber of Industry and Commerce (IHK) Frankfurt. Currently, making new applications is plausible in the Frankfurt network area. However, further capacities could only be implemented if notice is given many years in advance, according to Mainova. “In general, the situation is under strain.”

How this will affect other companies remains unclear, as the upcoming electrification of mobility, industry, and heating could also increase demand.

In response to these shortfalls, Berlin has replaced the first-come, first-served approach for the allocation of network connections in 2024 with an allocation procedure comparable to that in Frankfurt in order to limit the demand for the available supply. According to the Federal Network Agency, there is currently no consensus on a nationwide rollout of this approach. This means that in most other regions, network connections are allocated on a first-come, first-served basis.

Even today, Mainova/NRM is investing heavily in the expansion of the power grid. According to Mainova, an initial performance improvement of the Frankfurt power grid is already halfway to completion. Furthermore, an expansion of the power grid is being planned: “We have set the course for doubling the current available capacity during the 2030s by commissioning new grid coupling points to the transmission network,” said the energy supplier. In addition, Mainova/NRM is installing new power lines of all voltage levels as well as new and modernized relay structures. This is intended in particular to prepare the ground for new data centers: “With the help of these ambitious measures, we want to ensure sufficient network capacities for the connection of new data centers with above-average power requirements, for instance,” explains Mainova.

How are data centers creating their own gas-powered source of energy

The Frankfurt Westside campus is home to FRA7, one of the many data centers owned by developer CyrusOne. At the end of 2024, local politicians celebrated the groundbreaking of FRA7, which was intended to prioritize sustainability as a flagship project. Barely a year later, the company announced a partnership with energy supplier EON to cover the further expansion from 84 MW to 126 MW using gas-powered generators – presumably because the additional energy could not be provided by the power grid.

According to Kilian Wagner, Head of Sustainable Digital Infrastructures at Bitkom, they are not aware of any other similar cases in Germany, even though the industry is intensively dealing with the topic of on-site generation. Marina Köhn, a scientist at the Federal Environment Agency, is convinced of the opposite: “This is not an isolated case, but one that occurs frequently in the Frankfurt area. Data centers without a connection to the power grid are building new power plants that run on the fossil fuel of natural gas.”

Pierre Terras, Corporate Program Lead at Beyond Fossil Fuels (BFF), also assumes that more gas is already being used by the data centers in Frankfurt. “We are only missing the public data on this.” He reports that, especially in the US and Ireland, the new alliance between data centers and the fossil gas lobby is already well documented.

Therefore, since energy cannot be obtained from the power grid, gas seems to be the ideal solution. This fossil fuel can be used flexibly and is available around the clock. “Two groups that have thus far not benefited much from each other are now connecting and seeing synergies,” says Thomas Fricke, who works as a security architect for cloud technologies in critical infrastructures.

It is often argued that gas power plants can be powered by hydrogen from renewable energies as soon as it becomes available in a cost-effective form. However, many experts believe that this development is still a long way off. Another argument in favor of gas is that the burden on the grid is eased when large consumers tap into their own energy sources. “But for those who rely on gas, there is a risk of sharp price increases for consumers and import dependency in the short or long term,” says energy economist Claudia Kemfert. “Moreover, local impacts such as noise and fine dust would also be overlooked, as well as the resulting CO2 emissions, of which we, as a society, must share the burden,” says Max Schulze, founder of the independent think tank SDI Alliance, which is committed to sustainable digital infrastructure.

Siemens Energy Germany is currently recording record revenue with the gas turbine business. When inquired, they state that gas availability is not the bottleneck at the moment. It also seems that the necessary permits for gas power plants are not difficult to obtain – not even in an industrial park that is actually focused on sustainability, as the FRA7 example shows. In fact, there are no clear responsibilities when it comes to approving the construction of a power plant. Even if it is usually granted by the regional councils in Hesse, the exact responsibility depends on the type and size of the power plant, says Mainova.

Data centers are using fossil gas in response to energy bottlenecks – and this has recently become the case in Frankfurt, too. These bottlenecks occur here and in other data center hotspots, often due solely to the high energy requirements of the industry.

Land is at a premium in Frankfurt

Many areas of the city are already populated with data centers. Anyone viewing the city from above can easily recognize the flat buildings that have emerged in highly populated areas such as Seckbach and Sossenheim, as well as along Weissmüllerstrasse and Hanauer Landstrasse. Operators like CyrusOne, NTT, and Equinix are densely packed side by side there.

The data centers are clustering together to form an urban area where land is becoming increasingly scarce –and they need a lot of space. With the rise of hyperscale and cloud data centers, the demand for plots of land with a minimum size of four hectares has significantly increased, as noted in the “Documentation on the Impulse Forum Data Centers FrankfurtRheinMain” back in 2021. The enormous land consumption is due to the construction of mainly single-story buildings, as these are much cheaper to build.

The required land is primarily located in commercial zones that are also used by other sectors. However, the data center operators, most of which have global presence, have a great advantage: In competing for land, they hardly have any financial constraints, as the costs for the land are negligible compared to the technical equipment. “The data center industry can pay several times the standard land value; almost all other industries and trades are often significantly outbid at this price level,” confirms Oliver Reul, spokesperson for the Frankfurt Economic Development Agency.

The report “Status and Development of the Data Center Location Germany” also states that data centers have a strong impact on land prices. Especially in a densely populated city such as Frankfurt, where data centers are sometimes located in areas close to residential zones, conflicts arise with neighbors who suffer from the emissions and noise.

“For many years, construction in Frankfurt was easy – if you owned a piece of land and had a connection to the grid, you could go ahead and build,” reports Max Kendl. In June 2022, however, the city adopted a data-center strategy intended to limit competition for land with other types of development. Since then, the further expansion of computing power has been limited to seven suitable zones within the city limits. “These are zones where data center clusters already exist, and industrial parks serve as a stepping stone where data centers may still be able to be built under certain circumstances. Apart from that, all commercial and industrial zones within the city limits are off the table,” says Kendl. He adds that these zones would not be available for the most part: “Some 75 hectares have been designated as suitable zones, which the city has also identified as its requirement until 2030, but this land is not empty. This means that there can’t actually be many more data centers,” says Kendl.

Thomas Hickmann of the municipal planning office in Frankfurt explains that the commercial development program approved by the city council assembly should be taken into account as an important consideration when drawing up development plans, but it is not binding.

It’s unclear whether this will really curb data center construction and resolve issues relating to displacement pressure. Other users have hardly any chance to access land in the suitable zones. As Kendl describes the situation, as soon as space becomes available here, the operators of the data centers swoop in. In the Seckbach district, for example, specific displacement effects can be observed: “This is a classic industrial site that has been under enormous pressure in recent years due to data center operators”: “They bought up every available square foot here because they can pay prices that no other commercial company can match.”

Then why are data centers relocating to other regions?

As it becomes increasingly difficult to settle in close proximity to DE-CIX, municipalities in Frankfurt – such as Hanau, Hattersheim, Offenbach, and Schwalbach – are sought-after locations for data centers.

As a result, the data center belt continues to expand. In July 2025, details of a mega project in Nierstein were announced. The new data center that the operator NTT is building there, starting in 2026, will have 480 MW of power. To put this into context, this is equivalent to the power demand of about 500,000 households, according to NTT.

Other regions are becoming increasingly attractive. Erik Schöddert (RWE) describes, for example, the region between Aachen, Bonn, Cologne, and Düsseldorf as one of the “most exciting in Germany.” Where coal was once used to generate power, high-performance digital parks with energy-intensive IT clusters are to be established. Two current investment announcements illustrate the dynamics in the Rhineland region: Microsoft is planning a third hyperscaler in Elsdorf, while Kramer & Crew has its sights on a 15 MW data center in Bedburg. Bedburg Mayor Sascha Solbach has emphasized the determination of the region and promised to ensure fast approval procedures. From the perspective of the “data gravity” phenomenon, it can be assumed that Microsoft’s billion-dollar investment in the Rhineland region is just the beginning, and that data center capacities in this region will also grow significantly in the future.

The Berlin region is also developing as a new expansion area. Currently, a number of new large-scale data centers are being planned there.

“It is now assumed that the growth of data centers in Germany will shift to where there is still power available,” says Max Kendl. And there is still enough of it all over Germany, says Klaus Landefeld, Director of Infrastructure and Networks at the Eco Internet Association.

Therefore, federal states with a lot of power available are becoming increasingly attractive. According to Max Schulze of the SDI Alliance think tank, municipalities in Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Brandenburg, and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern already receive 100 to 200 requests from data center operators every month.

Many of these regions are experiencing the same problems as Frankfurt. In Berlin and Brandenburg, the second largest data center hotspot, the new construction and expansion, with the expected significant power demand of the data centers, will further burden an already strained energy market. Nevertheless, the massive expansion in Germany does not yet seem to be leading to network instability because, if problems are foreseeable in this regard, the network operators would rather not grant a grid connection to a data center in case of doubt.

This highlights the difficulty of reconciling long-term planning for the expansion of the power grid – which is essential, not least for the energy transition – with the short-term demands of large consumers such as data centers, which are also highly concentrated in certain regions. The BMWI report titled Status and Development of the Data Center Location of Germany also comes to this conclusion and states the following: “It is also unclear in this context to what extent network development planning should take into account the uncertain needs of companies.”

If potential large consumers are factored into the plans early in the power grid infrastructure, it enables faster grid connections and reduces delays in system transformation, that is, in the energy transition. However, there is also the risk of inefficient network expansion. When planned projects are canceled or not implemented to the originally specified scope, a lot of money flows into “dead” infrastructure.

Who foots the bill in the end?

Electricity prices in Germany are made up of several components, primarily the wholesale price of electricity — which is uniform nationwide — and regionally varying grid fees that cover the cost of transmitting power from generators to end users. As large, round-the-clock consumers, data centers influence both elements of this pricing structure, albeit in different ways.

At present, there is no direct evidence that German end customers are co-financing grid expansion for data centers. “We do have a national power market. The grid fees do indeed differ regionally, but in Hesse they are not higher than in other comparable regions,” says Ralph Hintemann, Senior Researcher at the Borderstep Institute. Any impact on consumer electricity prices would therefore be “only very indirect and minimal at most.” This assessment is also reflected in a comparison of electricity costs across Germany’s federal states.

Higher overall electricity demand — including that generated by data centers — does contribute to upward pressure on wholesale prices. However, because Germany operates a single electricity price zone, this effect is distributed across the entire country, meaning the price increase attributable to data centers is marginal for individual consumers. A direct causal link remains difficult to prove, as other market factors also influence price movements, according to Klaus Landefeld of eco-Verband.

Regional grid fees tell a more complex story. While it cannot be ruled out that end customers near data center hubs could face higher charges in the future, Frankfurt and Hesse currently do not stand out in this respect. In fact, grid fees are already higher in northern states such as Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Schleswig-Holstein due to the costs of integrating renewable energy infrastructure. “It’s simply the mechanism whereby the cost of grid expansion is ultimately passed on to end customers,” says Jens Gröger of the Öko-Institut, though he notes that a direct link to data centers remains difficult to substantiate.

What is already clear is that data centers benefit from preferential treatment. Under Section 19 of the Electricity Network Charge Ordinance, they can qualify for significantly reduced network charges, confirmed by Judith Henke, spokesperson for the Federal Network Agency. Industry bodies Bitkom and the German Data Center Association are also pushing for full exemption from energy tax and access to industrial electricity rates. Should such measures be implemented, the financial burden would not disappear, it would instead be shifted onto other consumers.

“As a consequence, someone else ultimately pays for the expansion of the grid,” Gröger concludes.

What if the AI hype is built on sand?

Sasha Luccioni, a researcher in the field of artificial intelligence and head of climate issues at Hugging Face, compares what we are currently experiencing to a “mass hallucination that we all believe in: that we need more data centers without really questioning why.” Marina Köhn of the Federal Environment Agency assesses the situation in a similar way: “The expansion of data centers is strongly driven by speculation based on the current AI hype and, unfortunately, not demand-oriented.”

In March of this year, Joe Tsai, Chair of the e-commerce giant Alibaba, also described how he sees the “beginning of some kind of bubble” in the market for data centers. OpenAI founderSam Altman recently also refused to rule this out.

This is due to the immense costs, both in the development and in the operation of data centers. As chips and other technologies are constantly evolving, data centers quickly lose value. By 2029, OpenAI is forecasting a cash burn rate, meaning a depletion of liquid assets, of a staggering 115 billion dollars. All this means is that ChatGPT is still a huge loss-making business despite its hundreds of millions of users and many subscribers. Moreover, there is currently only limited evidence that the technology will really pay off. This was shown, for example, in an analysis by The Financial Times, which evaluated hundreds of company records and protocols from S&P 500 companies from last year.

This also raises the question: Are our data centers really being fully utilized? There are rumors among industry insiders that not all of the land is truly leased, and that some of it appears to be held back as a contingency for meeting future needs. This could mean that, in reality, the need for additional computing power is much lower than expected. Conclusions could be drawn from the energy consumption of the individual data centers, but the underlying data is unsatisfactory.

According to the Borderstep Institute in Germany, 73 percent of data centers have submitted information on their energy consumption to the new, mandatory Data Center Register, but this kind of data is still lacking in general, particularly for larger data centers. Is there already much more being built than will ever be needed? And what happens when the bubble bursts?

If this happens, some investors could lose large amounts of money. Big tech companies like Microsoft, Meta, and Google will almost certainly survive a crash, as their business models are highly diversified. Network operators – and ultimately also municipalities – could end up sitting on hectares of dead infrastructure.

Furthermore, the oversized network expansion, which would no longer be needed, could lead to significant stranded assets – the risk that invested capital will not be recovered through profits. And then the question is: Who bears the cost? Given the significant amount of CO2 already emitted into the atmosphere, the answer is clear: People will all bear these costs. Experts stress that it is urgently necessary to control the construction and expansion of digital infrastructure to protect consumers, municipalities, and the climate.

This investigation is published in collaboration with AlgorithmWatch and is supported by EDRI, ECNL, and Lighthouse Report’s Investigative Journalism & Civil Society Collaboration Grant.

Authors