Generative AI is Already Catalyzing Disinformation. How Long Until Chatbots Manipulate Us Directly?

Zak Rogoff / Oct 23, 2023Zak Rogoff is research manager at Ranking Digital Rights.

Over the last few years, it's become clear that unscrupulous companies and politicians are willing to pursue any new technology that promises the ability to manipulate opinion at scale. Generative AI represents the latest wave of such technologies. Despite the fact that the potential harms are already apparent, law- and policymakers have to date failed to put the necessary guardrails in place.

The Perils of Personal Data and Political Manipulation

In 2018, concerns that were long the particular focus of tech experts and the digital rights community exploded into the mainstream, as the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed the massive collection of personal data with the goal of manipulating the outcome of elections: not only the 2016 election of Donald Trump and the Brexit referendum in the UK, but elections in another 200 in countries globally as well. Though the scandal captured headlines for weeks, with proclamations that “Facebook trust levels” had “collapsed,” as The Guardian put it just one year later, “the Cambridge Analytica scandal changed the world—but it didn’t change Facebook.”

But Cambridge Analytica was the tip of the proverbial iceberg, as politicians kicked off other experiments to try to manipulate the public. For instance, a 2022 Human Rights Watch report details political manipulation powered by user data that took place during the reelection of Hungary’s leader Viktor Orbán, four years after the Cambridge Analytica revelations became public. The report found that Hungarian political parties across the spectrum had continued to invest in the now commonplace practice of data-driven campaigning, using robust voter databases to power highly targeted advertising on social media. But, perhaps most ominously, the report found that the reigning Fidesz party had made use of data collected for the administration of public services, as well as other invasions of privacy, to unethically bolster its database, known colloquially as the “Kubatov list.”

In 2024, over 50 countries are set to hold elections. Unfortunately, current advances in the use of generative AI could supercharge the ability of political campaigns like Orbán’s to combine personal data with the ability to generate content in order to influence electoral behavior in their favor more effectively and efficiently than ever. This may be particularly true in undemocratic countries where information asymmetries are already so stark.

The media has, not surprisingly, already begun ringing the alarm on 2024, with NPR wondering “How real is the threat of deepfakes in the 2024 election?” and others worrying about the cheap, quick production of various types of manipulative content and disinformation, which could be created with AI tools and then spread by people online. Some limited use of generative AI has already crept into disinformation campaigns worldwide, and concerns have been raised about OpenAI’s lax enforcement of its policy against generating targeted political materials, for example: “Write a message encouraging suburban women in their 40s to vote for Trump.”

Intimate Interactions

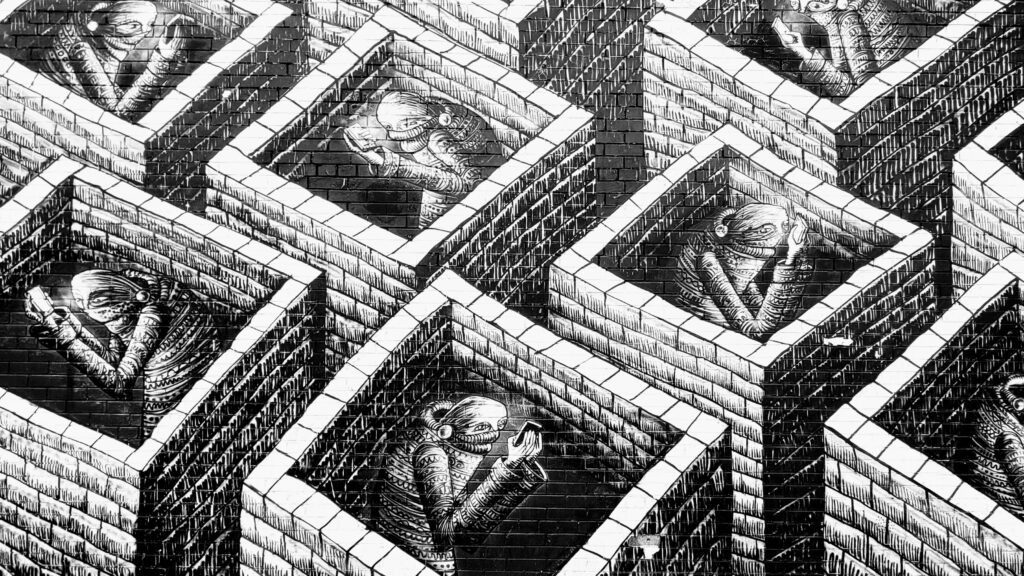

The threat of bad actors using AI to generate disinformation, which they would then spread themselves, is indeed very real. But, there’s actually another way generative AI could be used to influence us that we aren’t talking about yet: through direct person-to-bot interactions with a chatbot, no intermediary required. Regardless of whether it's meant to answer questions, generate art, or simply dispel our loneliness — once we are talking to it, it is possible for us to be manipulated by it, and the more data it has about us, the better it is likely to be able to do that.

It should be noted that, currently, we have no evidence of a chatbot designed primarily to manipulate people — all evidence of undisclosed bias in chatbots seems unintentional so far, and chatbots with an ideological bent (like those created by Elon Musk, some Chinese companies, and even a YouTube prankster) have not hid this fact. But engineers have already warned that a less transparent generation of manipulative chatbots are coming—and it would be surprising if more did not emerge before the end of the many 2024 elections.

To understand why, let’s go back 30 years, when an online banner ad, for AT&T, first directed us to an advertisers’ website. With a 44% click rate for this AT&T’s ad, Yahoo! soon began selling its own banner ads just one year later, as it transformed itself from a web directory into a commercial business. Not long after, it went on to create the first keyword-based ad. In short, the success of the first banner ad had, in almost no time, kicked off a new world of digital advertising — which was followed by mobile in the early 2000s. Ever since, companies have been engaged in an escalating arms race to figure out how to best manipulate us through digital technology. Since the beginning of the commercial internet, there has never been a clear line between commercial and political advertising online — the same platforms serve both types of ads, and similar data can be useful for targeting, whether to sell products or politics.

Just remember that, before digital advertising even existed, “ad men” were marshaling huge resources to try to convince people that cigarettes were good for you. Today’s online advertising world is equally competitive, insufficiently accountable, and much harder to police. With the growth of surveillance advertising, the platforms have let their algorithms discriminate by race and, eager to capture as much market share as possible, allowed their systems to grow too fast for them to reliably keep out disinformation campaigns. What’s more, the potential for big pay-offs in the advertising and influence economy encourages creative but unscrupulous behavior. These same market forces spurred Macedonian teenagers to create fake 2016 election news for ad revenue and fueled the historic, decades-long evisceration of privacy norms by Big Tech.

If chatbots with the latest generative AI capabilities truly have the potential to provide new manipulation capabilities, history teaches us that there is always a dark corner of the advertising world—whether pushing a sketchy product or trying to sway an election through political disinformation—that is going to figure out how to unlock those capabilities. Alongside commercial advertisers, political actors like Orbán are almost certainly waiting for this tech with their wallets open.

Why existing safeguards are inadequate

How can we make sure these forces don’t give birth to a generation of manipulative chatbots that push us into choices that go against our values or interests? Unfortunately, for the moment, governments and regulators have yet to step up to the plate when it comes to ensuring rights-respecting, transparent AI. Despite some strongly worded statements by regulators, and a lot of public scrutiny on generative AI services, the fact is that we simply do not have the necessary safeguards in place, and the ones currently being developed by our lawmakers are insufficient to prevent the rise of manipulative chatbots.

To better understand why this is the case, let’s take the example of Snapchat’s My AI generative chatbot. According to Snapchat’s website, its goal is simple: helping us out by doing things like “answer burning trivia questions” and “offer advice on the perfect gift for your BFF’s birthday.” However, unbeknownst to most users, everything they tell or share with the chatbot is algorithmically harvested for later use in targeted advertising. This means that the system is already interacting with users for a purpose they are unlikely to be aware of— for someone else’s commercial benefit. Though, in its current form, this may not be considered extremely harmful, the industry’s profit motive could push such a system to develop in a more clearly manipulative direction.

Fishing for information

If companies deploying chatbots like My AI were to find themselves under pressure to increase the profitability of their chatbots, they may have an imperative to secretly steer conversations with users, nudging the users to divulge more or different information than they would have otherwise, providing more fuel for advertising and a corresponding earnings boost. Snapchat already has an incentive to do this; and there is no way to know for certain that it is not already doing so.

This kind of nudging would not be clearly illegal in the US or the EU. Even after the EU’s AI Act becomes law, which is expected to happen in 2026, it is still not clear that it would become illegal. This is because, factoring in recent changes that were made to account for the rise of generative AI services, the AI Act would only make algorithmic manipulation illegal if it was kept secret and caused people to do something they would not otherwise have done, in a way that caused “psychological or physical harm” or “exploit[ed] the vulnerabilities of vulnerable groups.” This broad yet vague provision would succeed at banning chatbots that convince people to send all their money to a fraudster, or that tried to convince children to eat Tide pods. But this is too high a threshold.

After all, don’t we deserve to know if an AI is trying to manipulate us, even if it’s just trying to get us to spend money on something we’ll later regret, or to change our minds about a social issue? These types of manipulations wouldn’t necessarily cause “psychological or physical harm,” but they would arguably impact our rights to cognitive liberty and control of our own time.

Secretly pushing a product

Falling further down this slippery slope, the natural next step for such a chatbot, after nudging users to divulge more information, would be to have it steer the user directly toward buying a particular product, for example one that the AI’s owner has been paid to promote.

Thankfully, this behavior would be somewhat constrained by existing law. For instance, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has made it clear that it would be illegally deceptive for a chatbot to do this without explicitly disclosing its business relationship with the product it was promoting. But even this protection is limited; as long as the chatbot’s creators could prove to a judge that they had sufficiently disclosed any deals they had made with other companies, their chatbots could legally attempt to manipulate people into buying those companies’ products.

Subliminally influencing life decisions

But what if the AI’s goal was not to just direct you toward a purchase, but rather another life decision, like joining the military, converting to a new religion, deciding not to get an abortion, or even voting for a preferred candidate? The system would not need to inject whole ideologies into people’s minds to be successful, just prime them by eliciting certain mental states. This could be done by, for example, appealing to existing biases – like a fear of immigrants, a sense of existential dread, or a belief in Hell and Heaven.

Here, existing and proposed laws in both the EU and the US remain unclear on whether it would be illegal, even if the manipulation is not detectable by the user (subliminal manipulation). The best legal tool against such a system may be found in a part of the EU AI Act that classifies systems with the potential to influence elections as “high risk.” This means, among other things, that they would need to disclose their “intended purpose” to the user, which could include an intent to influence life decisions. But there isn’t enough detail in the legislation for us to be confident that this will result in a clear disclosure that users would actually understand; after all, tech companies lead the world in finding clever ways to meet such vague disclosure requirements with turgid user agreements we are not equipped to understand. And, of course, this rule will not be settled law in time for the 2024 elections, nor do anything to stop less explicit political manipulation.

It is, of course, worth asking whether such manipulation would actually work. We don’t want to add to tech companies’ existing efforts at generating over-the-top hype about AI capabilities, and creating a greater mystique around these systems than already exists. But we do know that generative AI is rapidly becoming more powerful. If the history of social media platforms teaches us anything, it’s that it is better to be proactive rather than reactive when it comes to tech regulation. Even if these systems turn out to be ineffective at manipulation in the near term, algorithmic manipulation in many forms is only likely to increase throughout the twenty-first century, as Shoshana Zuboff warned half a decade ago in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. This is the right moment to make sure proper safeguards are finally put in place that will firmly protect us against whatever abuses Big Tech firms, and anyone else with access to these technologies, might have in store for us next.

A pivotal time, in more ways than one

As we know, the many elections of 2024, from the US to South Africa to the UK, will take place just as generative AI tools are proliferating far ahead of regulators' ability to keep them aligned with our most basic rights. Considering the wealth of new opportunities to do harm through the use of generative AI, companies that truly wish to be responsible in how they use this new technology, as many have proclaimed to, need to take an active role in cultivating user trust, transparency, and accountability.

To achieve this, Ranking Digital Rights has developed draft human rights standards for our upcoming Generative AI Accountability Scorecard, building on our ten years of experience ranking tech and telecom companies according to their respect for human rights. Among a number of measures, it recommends that companies producing chatbots and other conversational systems commit to maintaining comprehensive and up-to-date disclosure about any business goals these bots are programmed to pursue in conversation. Such disclosures would need to be conspicuously visible to users before the launch of the system, just as some chatbots, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, currently provide a concise, highly visible disclaimer about the potential inaccuracy of chatbot-generated results.

If we make sure such a disclosure becomes the norm now, tech companies will have a harder time secretly changing their policies in the future, and those with sinister intentions will attract scrutiny when they release systems without such a disclaimer. If a US company changed the goals of its conversational AI without updating the disclosure, the FTC might even be able to go after it for deceptive business practices. But even if we do succeed in building this norm, with support from the FTC and similar agencies abroad, we also need solid laws to hold companies to account, and that will mean an expansion of proposed laws like the EU AI Act and the introduction of analogous laws across all jurisdictions.

The struggle to ensure governments keep pace with this rapid evolution of new technology has been rendered more difficult as the interests of many lawmakers have clearly been captured, at least in part, by intensive and successful Big Tech lobbying campaigns. News of OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s closed-door dinners with lawmakers in the US can hardly inspire confidence in the willingness of Congress to regulate his company or others like it.

But we, the public, have now lived through the techlash— and this decreasing confidence in Big Tech experienced post-Cambridge Analytica has only worsened following the pandemic. We are no longer passive consumers dazzled by shiny new toys. With this in mind, we need to push now for stronger laws that will finally constrain the behavior of tech companies. And we must do so before they begin wielding the gargantuan power generative AI has bestowed upon them to manipulate us in new ways and, in doing so, create novel and threatening consequences for our political systems and for our democracies.

Authors