Generative AI and Hollywood Can Co-Exist

Maggie Engler, Numa Dhamani / Oct 11, 2023Numa Dhamani is an engineer and researcher working at the intersection of technology and society at KUNGFU.AI. Maggie Engler is an engineer and researcher currently working on safety for large language models at Inflection AI. Numa and Maggie co-authored a forthcoming book, Introduction to Generative AI: An Ethical, Societal, and Legal Overview.

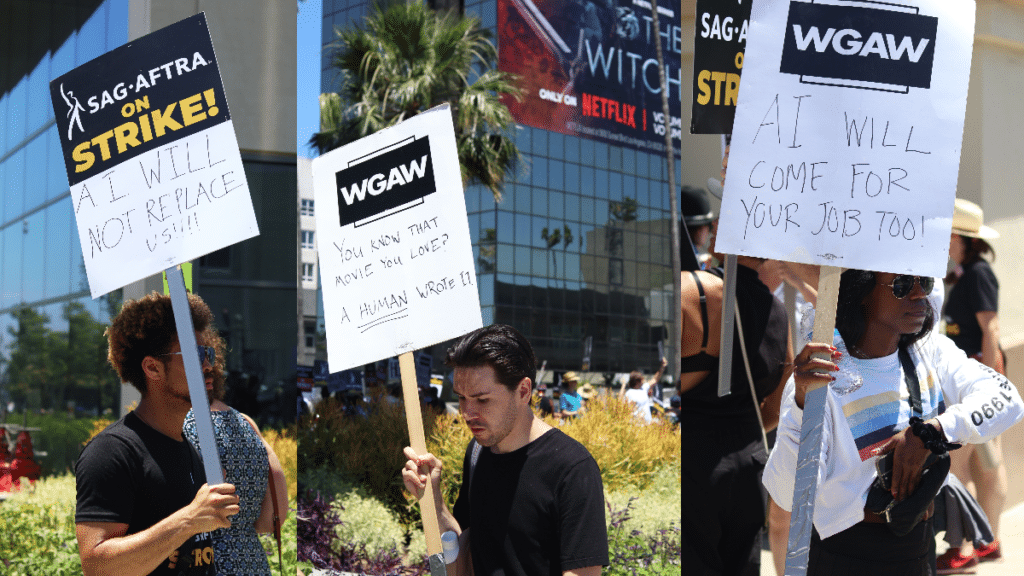

Late last month, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike officially ended after 148 days with the signing of a tentative new contract agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). Negotiations between the WGA, which represents some 11,500 screenwriters, and the studios began in April; the strike was called after the studios initially refused to concede several of the writers' demands, which included standard fare like staffing minimums and bonus payments from streaming services. But one of the key points of contention was new: the use of generative AI in screenwriting.

At the start of the talks, the studios claimed that the technology was too nascent to include in their agreements, and pushed to defer the issue for three years, the duration of the contracts. But the writers refused to budge: this year, AI has been impossible to ignore. Members of WGA saw the content generated by ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) and feared that the tools would be used to reduce the number of working hours available to screenwriters. Members of SAG-AFTRA, the actors' union, are in the midst of their own 90-odd day work stoppage, and hope to secure protections against the use of generative AI to digitally alter their performances, which could similarly result in reduced work opportunities — you don't need an actor to come in for recordings if you are able to generate convincing video of them saying and doing anything the script requires.

The idea of using computers, and even AI, for film production is not a new one. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) was used as early as 1958, in the opening credits of the Alfred Hitchcock film Vertigo; the technique took off in the 1990s with advances in computer graphics and virtual cinematography. More recently, AI has been used to make actors look like older or younger versions of themselves, or even to complete scenes when the original actor has died, like the late Paul Walker in Furious 7and Peter Rushing of Star Wars. In each of these cases, the directors filmed a lookalike who acted out the parts, then used visual effects — based on hours of previous footage — over their faces in post-production.

But within the last year, generative AI models have made it significantly easier to generate convincing audio and video with only a few minutes of recording, one of the key concerns of SAG-AFTRA. The documentarian Morgan Neville drew significant criticism for using AI-generated audio of the late Anthony Bourdain's voice reading an email passage aloud in his documentary on Bourdain, Roadrunner, after the real Bourdain died by suicide in 2018. The unique ethical quandaries of that situation notwithstanding, it serves as a reminder to anyone with a public profile that they no longer have full control of their image and voice. Text-to-speech and text-to-image models, both of which have exploded in popularity over the last two years, have already proven capable of creating convincing fakes of actors' voices, mannerisms, and styles. It's no wonder that the actors guild is also hoping to secure with this contract some legal protections against generative AI, the type of AI largely responsible for the recent breakthroughs.

Generative AI technology — which includes LLMs, text-to-speech, text-to-image and even text-to-video tools — refers to models that can generate text, images, sounds, animation, 3D models, and other forms of content based on the patterns and structures of the data they were trained on. These models are trained on vast quantities of unstructured data from the internet containing billions or trillions of examples, often building on copyrighted work of artists without their consent.

For the entertainment industry, the concern isn’t just that generative AI models could replace their livelihoods, but AI-generated scripts or movies could partly be based on the existing work of writers and filmmakers. Per the summary of the WGA agreement, “The WGA reserves the right to assert that exploitation of writers’ material to train AI is prohibited by [the contract] or other law.” But it remains to be seen how this could be enforced, especially given the unclear relationship between generative AI models and copyright material. Of course, this agreement certainly gives writers some leverage with the studios, but it may be tricky to enforce this stipulation, given that they don’t have a contractual agreement with the AI companies developing these models in the first place. Similarly, the SAG-AFTRA members also voted to organize a strike against the video game industry trying to negotiate protections for training AI models with their voices.

While we are able to generate contextually relevant content based on the patterns learned from these massive internet-based datasets, these models lack genuine understanding and intuition, relying solely on statistical patterns. In addition to the concerns around copyright infringement, generative AI models have several limitations, from amplifying stereotypical and derogatory associations to hallucinating nonsensical or inaccurate content. Not only do humans play a vital role in providing the nuanced understanding and knowledge that is required to make the content worthwhile, but they also play a crucial role in setting ethical boundaries and ensuring the responsible use of generative AI models. This summer, Buzzfeed published a now-deleted article with AI-generated images of Barbies that caused a social media uproar. The authors used a text-to-image service, Midjourney, to generate 195 Barbies from around the world. But the images were racist and culturally insensitive –– in two examples, the Sudanese Barbie was holding a machine gun, and the German Barbie was portrayed as a SS Nazi General. Left unchecked, generative AI writing scripts or developing movies could potentially be disastrous.

Of course, the extreme scenario of fully AI-created movies is unlikely anytime in the near future; there remains a strong need for human vision and curation. The WGA agreement suggests a future where humans and AI collaborate, which should certainly be applauded — it doesn’t outright ban the use of generative AI technology, and allows for experimentation and the ability for writers to do parts of their jobs more quickly and effectively. This is exactly how generative AI technology is designed to be used, with human expertise and oversight. But because tools powered by generative AI will speed up certain parts of the production process, Hollywood writers and actors are right to use their collective power to extract protections from studios. It's not only Hollywood that will be affected by generative AI, either: the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes provide a useful blueprint for engaging with emerging technology head-on, and policymakers should consider the compromises achieved in the WGA agreement, and what Eryk Salvaggio describes as its four key points — authority, agency, disclosure, and consent — as they look towards formulating broader economic policy around workforce disruption by AI.

Authors