Five Takeaways from the DOJ’s Case in the Google Ad Tech Trial

Karina Montoya / Sep 23, 2024Karina Montoya researches and reports on broad media competition issues and data privacy at the Center for Journalism & Liberty, a program of the Open Markets Institute, in Washington, D.C.

Shutterstock

The antitrust trial against Google for allegedly illegally monopolizing digital advertising technologies (ad tech) enters its third week today. The case focuses narrowly on the industry that intermediates sales of open display ads — sold primarily on news websites — through three key products: publisher ad servers, ad-buying tools, and ad exchanges.

Last Friday, the Department of Justice rested its case after presenting 38 testimonies — 25 of them from witnesses who took the stand, with the rest being video and read-ins. Witnesses included representatives from news publishers, ad agencies, and ad tech companies, providing insight into the segments of the market in which Google is dominant.

This parade of witnesses depicted a digital advertising market in which it is difficult for publishers to escape their reliance on Google, rival publisher ad servers and ad exchanges can’t grow, and ads are transacted by Google in ways that reinforce its dominance.

Here are five takeaways from the last two weeks.

1. Google’s “trifecta of monopolies” in display ads

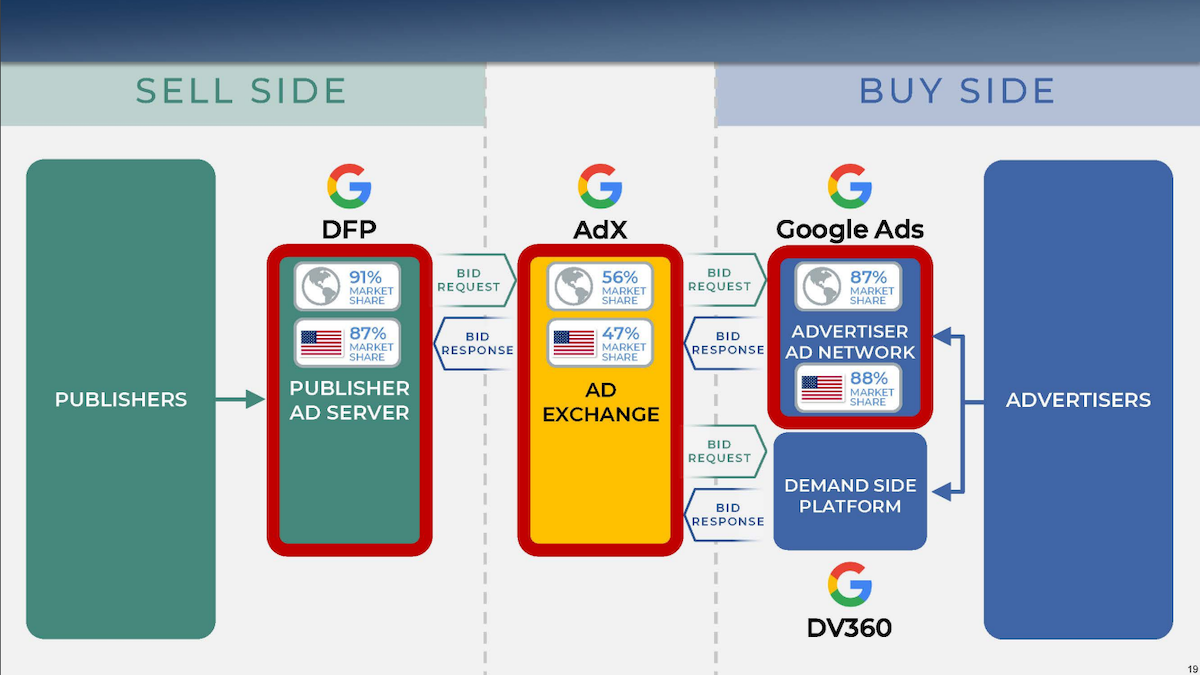

The DOJ’s opening statements set the tone for the trial by describing Google’s ad tech operations as a “trifecta of monopolies.” The presentation included a graphic that detailed Google’s market share on the sell-side and buy-side products is well over 80 percent, with its ad exchange in the middle, clearing about 50 percent of ad impressions in the US and globally.

Structure of ad tech market, per DOJ's opening statements presentation. Access the presentation here.

This is the backbone infrastructure for news publishers to sell what is known as programmatic ads: the ad inventory that is left after selling ads through direct contracts with advertisers. It is a highly automated market that relies on real-time bids from advertisers — represented by ad-buying tools — for a chance to show their ads to readers.

Throughout the cross-examination of witnesses, Google’s attorneys attempted to frame programmatic display ads as substitutable by ads on social media, video platforms, mobile ads, and game consoles — which will be key for Google’s rebuttal case. But, witnesses gave specific answers about where in the ad tech stack they compete against Google.

Some of them, particularly those who are customers of Google’s ad exchange AdX, did not shy away from expressing their grievances. “We’ve been buying from AdX since 2011. Google is draconian and an absolutist, and they have not taken our feedback,” said Jed Dederick, chief revenue officer at The Trade Desk, to Google’s attorneys.

2. Publishers trapped in a Google-DoubleClick world

The DOJ mostly leaned on examples of how Google’s practices harmed news publishers following its acquisition of DoubleClick in 2008. For the DOJ, the event that set the stage for Google’s abuse of dominance in this market was its decision to integrate DoubleClick’s ad server DFP with its ad exchange AdX, and to turn them into the only channel to access Google’s massive ad demand (the Google Ads network) through real-time ad auctions.

We learned that publishers see this integration as a form of ‘tying’ that makes them more reliant on Google's ad tech, despite their efforts to diversify demand sources. Former News Corp vice president of data and ad tech, Stephanie Layser, and Gannett/USA Today’s vice president of revenue operations, Tim Wolfe, gave similar accounts: no matter how many ad exchanges they connected with to diversify their advertiser demand and reduce overreliance on Google, Google’s AdX ad exchange ends up clearing most of their ad sales.

Wolfe revealed that 50 percent of Gannett’s programmatic ad sales come from AdX, for which the publisher pays $10 million in fees a year. Layer said News Corp tried to switch ad servers in 2017, at a time when the publisher earned up to 60 percent of its ad impressions from AdX. NewsCorp ultimately abandoned the plan out of fear that it would not be able to replace the revenue from outside of Google’s system.

3. “Irrationally high rents” paid by publishers through AdX

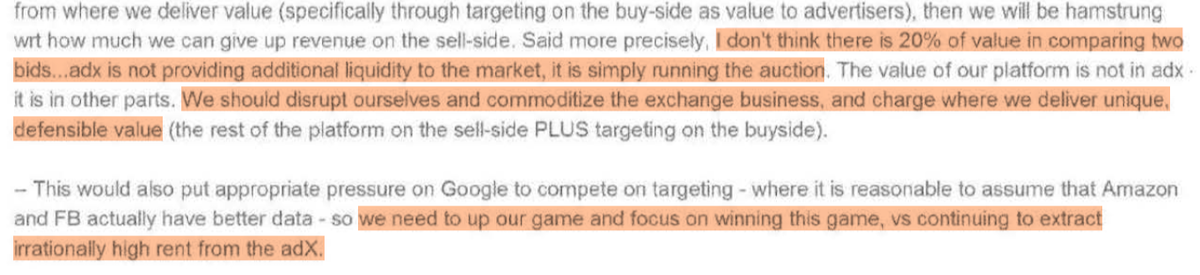

One of the most compelling points of evidence on Google’s ability to leverage its dominance on one side of the market (advertiser demand) to entrench itself into another side (ad exchanges and ad servers) came through a series of comments on Google’s internal documents, in which executives discuss the “real value” of Google’s AdX, which takes a 20 percent cut per each dollar spent. In short, Google’s middleman business depends on its exclusive access to the Google Ads network that publishers couldn’t find anywhere else.

In such comments (using Google Docs, of course), Chris LaSala, Google’s former managing director of publisher platforms, and other top executives acknowledged that AdX taking 20 percent off each ad dollar transacted on Google’s ad server is a form of extracting “irrationally high rents” and that it was not “long-term defensible” behavior.

Comment written by former Google executive Chris LaSala in an internal file about ad tech prices affecting publishers. Access the exhibit here.

During examination by the DOJ, LaSala said he “did not like this business” and that he would have preferred Google to focus more on the ad network side.

Fees charged by ad exchanges are layered atop other fees charged by ad tech used by advertisers, which in turn reduces ad revenues for publishers. Additional exhibits showed Google considered lowering its ad exchange fees at or below the average 10 percent charged by competitors, but it didn’t do so out of “risk of more platform competition.”

4. Google uses the IAB in war against rival technologies

Another important argument for the DOJ to show Google’s abuse of market power is its retaliation against technologies that challenged its control of publishers’ ad inventory. Brian O’Kelley, former CEO of ad exchange AppNexus (later known as Xandr, now owned by Microsoft), shared new insights into how Google did this.

In a video testimony, O’Kelley explained how publishers and other ad tech companies developed a new type of auction outside of Google’s AdX, where all ad exchanges competed for ad inventory at the same time, which they dubbed ‘header bidding.’

Header bidding rose around 2014 out of publishers’ frustrations with Google. Google’s AdX was not only the first to bid on ad impressions on Google’s ad server, but it also had the ability to look at the prices offered by its rivals – essentially, to win every time it wanted. But Google’s rivals, on the other hand, couldn’t do the same. This lack of real competition reduced publishers’ ad revenues, so header bidding quickly reverted that situation.

Around 2015, O’Kelley and other co-founders turned this type of auction into an open-source product called Prebid, now overseen by the organization Prebid.org. O’Kelley said the only reason they founded this organization was because Google leveraged its influence over the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) to knee-cap header bidding’s rising popularity.

Before launching Prebid.org in 2017, he said, they presented Prebid to the IAB Tech Lab, a body of the IAB that “develops foundational technology and standards” for digital media, so that it could be adopted more widely. But Google, the largest IAB funder with a seat on the board, “opposed vehemently.” In all these years, Google has never directly participated in Prebid.

5. Google’s “data advantage” and the connection with its search monopoly

Although the legal focus in the case is not on Google’s leverage of specific sets of data, several witnesses have made the point that Google’s “data advantage” exists in different levels of its tech stack, and it creates conflicts of interest that can be exploited to protect its dominance.

O’Kelley gave one example. Assuming that you, as Google, could find out the advertiser or the ad network they used to make a bid, “you could figure out why this advertiser is working with a competitor,” O’Kelley explained. “The scary part of this would be if you see Coca-Cola buying exclusively through one ad exchange, it would be very tempting to go to your sales team to find out why they are working only with PubMatic. ‘You know, let’s see if we can give them a better rate.’” The more data you have about different bid prices, said O’Kelley, the better you can manage yield on behalf of publishers or your own ad exchange.

Google’s ad tech tools also get a leg up from its own ad inventory, said Jed Dederick at The Trade Desk (TTD), a Google competitor on the buy side that caters to large advertisers. All of TTD’s clients use Google’s DV360 platform, he said, because it is the only way to access ad inventory on Google’s properties: YouTube and Search.

At its core, Google’s dominance of ad tech for display ads would not exist without search. “Google has a massive advantage for its access to data on 2 billion logged-in users on search,” Dederick said. Back when the monetization of the internet was taking shape, advertisers had more demand than what Google Search could provide, so Google entered the business of “banner ads” to satisfy that demand.

The one thing that has changed ahead of this ad tech trial is that another federal judge has already ruled Google reached such dominance over search ads by breaking antitrust law. Although this ruling will be appealed by Google, it remains to be seen how this will be considered by Judge Brinkema in the current case.

Google’s attorneys expect to finish their case this week. If so, the DOJ will then have another chance to recall witnesses, and a date will be set for closing arguments. With that, we may be heading into the last days of the trial.

Related Reading:

Authors