First Transparency Reports Under Digital Services Act Are Difficult to Compare

Gabby Miller / Nov 22, 2023

European Commission headquarters in Brussels, 2019.

Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA) requires that the largest tech firms submit regular transparency reports to stay compliant with the law. The deadline for Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Search Engines (VLOSEs) to publish their first reports was Nov. 6, with all fifteen service providers that meet the “very large” threshold making the cutoff. And though the community of DSA watchers made some initial observations, the transparency reports received little press or public attention.

In the days following the release of the reports, Tech Policy Press updated its DSA tracker to include links to the reports, ad repositories, notice and action mechanism portals, and points of contacts for DSA-related inquiries. (The firm Tremau is similarly tracking DSA developments.) Even a cursory glance at the various documents provided by the companies, however, raises several questions, particularly around the lack of transparency reporting standardization, varying degrees of disclosure, and seemingly different interpretations of DSA Articles that VLOPs and VLOSEs are obligated to comply with. An initial comparative analysis suggests that a more thorough investigation of the reports will yield worthwhile insights, and that the European Commission has the opportunity to issue more specific instructions to make these reports more useful to researchers, journalists, and the public.

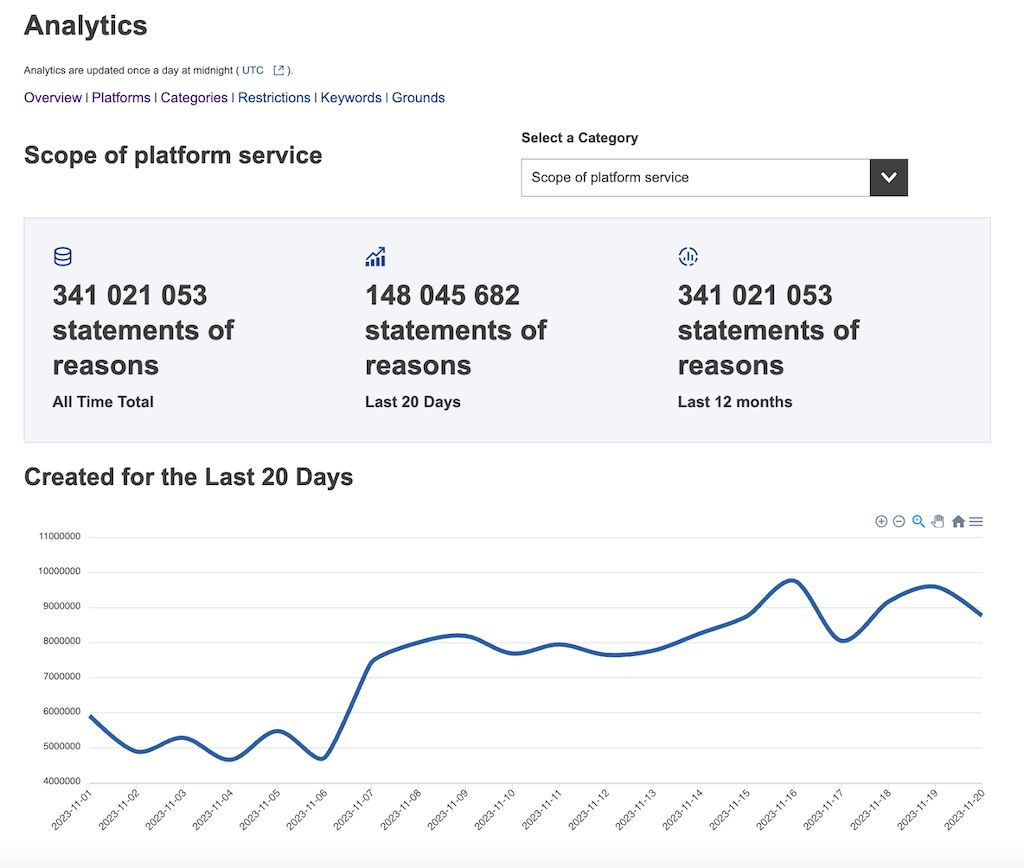

The EU Commission also recently released a ‘DSA Transparency Database.’ While it contains heaps of data and instructions, its less-than-intuitive design likely means highly technical researchers will benefit most from the database. Still, it’s a vast improvement from pre-DSA times, when platforms provided little to no data on their content moderation activities.

Key Takeaways:

- A lack of standardization makes it difficult for researchers to do comparative analyses across transparency reports.

- The quality and granularity of these reports varies dramatically; a working template, made publicly available, could alleviate some of these discrepancies.

- Service providers appear to have interpreted certain DSA Articles and definitions differently, leading to missing or incomplete data.

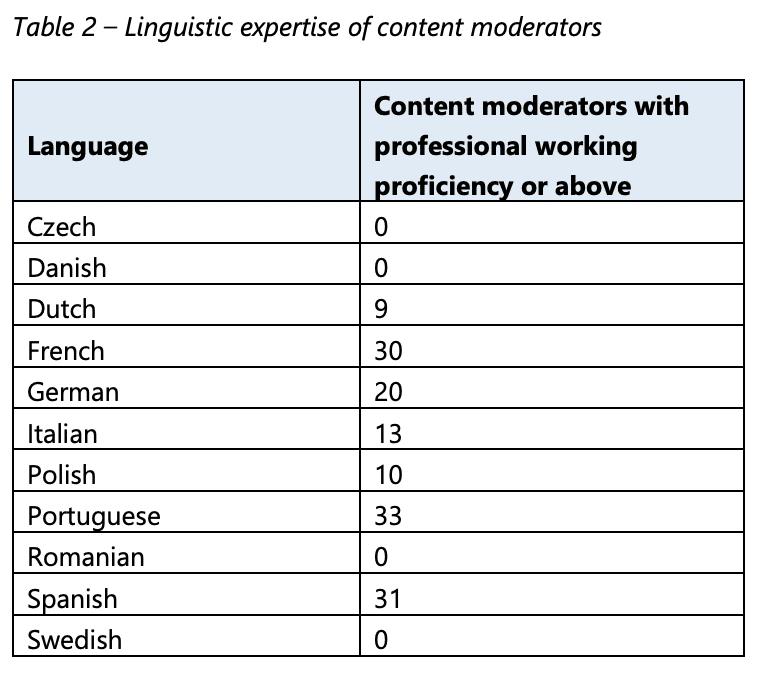

- Linguistic expertise disclosure requirements could be more clear, such as which language specializations must be reported and how content moderators are counted.

- The EU Commission has many gaps to fill, far beyond what this report has examined, before the next round of transparency reports are released.

- Questions remain whether these reports will actually shift industry standards, both in the EU and globally.

Case Study: Comparing Very Large Online Search Engines

Try comparing Microsoft’s Bing and Google Search, the only two designated Very Large Online Search Engines, whose reports show two very different pictures of ‘own initiative content moderation’ practices. The DSA obliges providers of intermediary services to make content moderation decisions publicly available in an ‘easily accessible’ and ‘machine-readable format.’ It also requires intermediaries to report, as applicable, the number of complaints received, broken down by the complaints’ basis, the decision taken by the intermediary, the median time needed for those decisions, and how many were reversed.

In its relatively short, six-page transparency report, Microsoft does not provide its content moderation activity in a machine-readable format. This is likely because Microsoft reported almost no quantitative data: it claims to have received “zero appeals of the types of decisions described” in Article 15(1)d via Bing’s internal complaint handling systems, and provided no further elaboration.

Google, on the other hand, clearly defined its appeals as the “unwarranted removal of content from or access to our services,” and broke them down by type of violation and ‘granularity,’ or at what level an action was being taken at, including: domain, host, url, incident, and partner feed item levels. The content moderation decisions for Search were appealed by users 642 times, and Ads on Search were appealed 179,151 for the reporting period.

There could be many factors that contribute to the large discrepancy between the two search providers in how they report content moderation appeals. Microsoft’s Bing and Google Search are, for one, dramatically different in terms of market share. As of July 2023, Google accounted for around 84 percent of the global desktop search market, whereas Bing accounted for only 9 percent, according to the web traffic analysis service StatCounter. The two platforms also track their respective content moderation numbers across different reporting periods, with Bing’s running a little over a month (Aug. 25, 2023 to Sept. 30, 2023) and Google’s only a couple of weeks (Aug. 28, 2023 to Sept. 10, 2023). Microsoft could be interpreting Article 15 slightly differently than Google, or maybe Microsoft’s appeal mechanism for Bing wasn’t as easily accessible or frictionless enough for users as Google’s is for its Search. And their respective terms and conditions as it pertains to service violations could also look dramatically different. (This raises other questions, though, as to whether Microsoft is doing enough to filter out illegal or harmful content in its search results.) The list goes on.

Microsoft did, however, report that it “took voluntary actions to detect, block, and report 35,633 items of suspected CSEAI [Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Imagery] content provided by recipients of the service” using its automated content detection tools in Bing Visual Search. Google says it similarly combats Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) – an umbrella term that appears to be distinct from CSEAI in that it sometimes includes not just images and videos but other formats like audio, too – also using automatic detection tools like “hash-matching technology.” However, in Google’s ‘own-initiative’ content moderation break-down, it does not have a distinct-CSAM violation category, with categories like “Pornography / Sexualised Content,” “Non-consensual Behaviour,” and “Protection of Minors” that may leave the public guessing how Google is internally categorizing CSAM on its search platform. It’s less than ideal that CSEAI and CSAM are terms often used interchangeably but have slightly different meanings, and are therefore not easy to compare.

What’s clear is that in the absence of even a rough template or more explicit guidance for Very Large Online Platforms and Search Engines, this first round of transparency reports leave at least as many questions as answers on close scrutiny. It also gives room for VLOPs and VLOSEs to evade cooperation with the regulator, whether explicitly or otherwise.

Content moderation languages

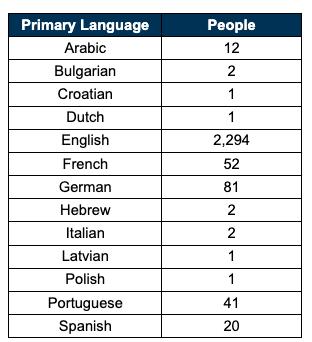

Linguistic expertise is another area where greater clarity could be useful. For instance, Google lays out in clear terms the complexities of “identifying the human resources who evaluate content across Google Services,” and clearly states that its numbers “do not represent the number of content moderators hired to review in each official EU language.” Instead, for YouTube specifically, the number of content moderators listed reflects someone who “reviewed at least 10 videos posted in an official EU Member State language” between Jan.1, 2023 and June 30, 2023.” This makes it difficult to analyze how Google distributes its human resources across languages, whereas similarly large and complex platforms like Meta have figured out how to. Whether a more careful and nuanced approach to assigning numerical values is more valuable than standardizing how to count linguistic specialists remains to be seen, and is largely dependent on what the EU Commission hopes to achieve by requesting such figures.

This could be as simple as seeing where there’s a severe lack of “human resources” in certain languages, especially amid ongoing conflicts and wars – times when harmful and illegal content tend to spike. For instance, entire EU-designated languages, such as Irish, Maltese, and Romanian, had little to no linguistic specialists across multiple service providers. The format used to report these figures is different in each report, as well. Some included every EU language and explicitly stated how many human moderators they employed by language-specialization – even when that number is zero. Others excluded entire languages from their list, making it unclear whether they wholly lack the linguistic expertise or they just didn’t include it in their count. And ‘content moderators’ were defined differently across several reports, with some counting internal moderators alongside contractors, and others not making the distinction. Questions abound on how to count full-time and part-time contractors, topic versus language experts, and language specialists who moderate content outside the EU but still in an official EU language.

Other notable findings

Some platforms appeared to put more effort into this exercise than others. Pinterest’s transparency report is one of the most detailed from a quantitative perspective, both centralizing and breaking down all relevant data in granular detail and easy-to-read charts, and could serve as a template for others to follow. Another bright spot relates to the DSA’s Article 15, which requires that service providers report the median time needed to take action on illegal content or terms and conditions violations as well as the median time needed between the illegal contents’ receipt and action. TikTok says the median time it takes to take action against illegal content is “approximately 13 hours,” and Google says it takes less than a day to do the same on YouTube, Google Play, and in its advertisements – both relatively quick turnaround times. Apple’s median time to moderate illegal content and terms and conditions violations in its App Store, however, is much longer: Apple’s median time is 8 days to take action and 11 days to make appeals decisions. Of course, the number of violations Apple receives is substantially lower than TikTok and Google, but these figures raise questions about the efficiency of content moderation in Apple’s App Store.

What’s next

Some companies have yet to satisfy their obligations fully. If Facebook, Google, and Wikipedia have listed their DSA “points of contact” online – contacts which are supposed to be made public and easily accessible so that Member States’ authorities, the Commission, and the Board can clearly communicate with each other – they are not readily available. LinkedIn did not provide the number of English-language linguistic specialists “with professional working proficiency or above,” writing that it “supports 12 of the 24 official languages in the EU” but only listing eleven of them..

Whether the DSA will compel platforms and search engines of all sizes to fall in line with a new set of developing transparency reporting standards – both in Europe and in other parts of the world – is unclear. In the interim, the EU Commission should consider issuing more specific guidelines on reporting that will identify the gaps in this first round of documents in order to ensure that platform accountability is maximized.

Authors