Facebook, the election, the insurrection: A conversation with Avaaz's Fadi Quran

Justin Hendrix / Mar 24, 2021This week Avaaz- a global activist organization that focuses on issues such as democratic values, human rights, and poverty- released a new report: Facebook: From Election to Insurrection: How Facebook Failed Voters and Nearly Set Democracy Aflame.

I spoke to Fadi Quran, Campaign Director at Avaaz, about the report and about the broader question of how democracies should hold tech platforms to account. The following is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

Justin Hendrix:

You've just released this report, which looks specifically at Facebook and the role that it played in the disinformation campaign that ultimately led to the violence on January 6th in the US Capitol. What are some of the key findings?

Fadi Quran:

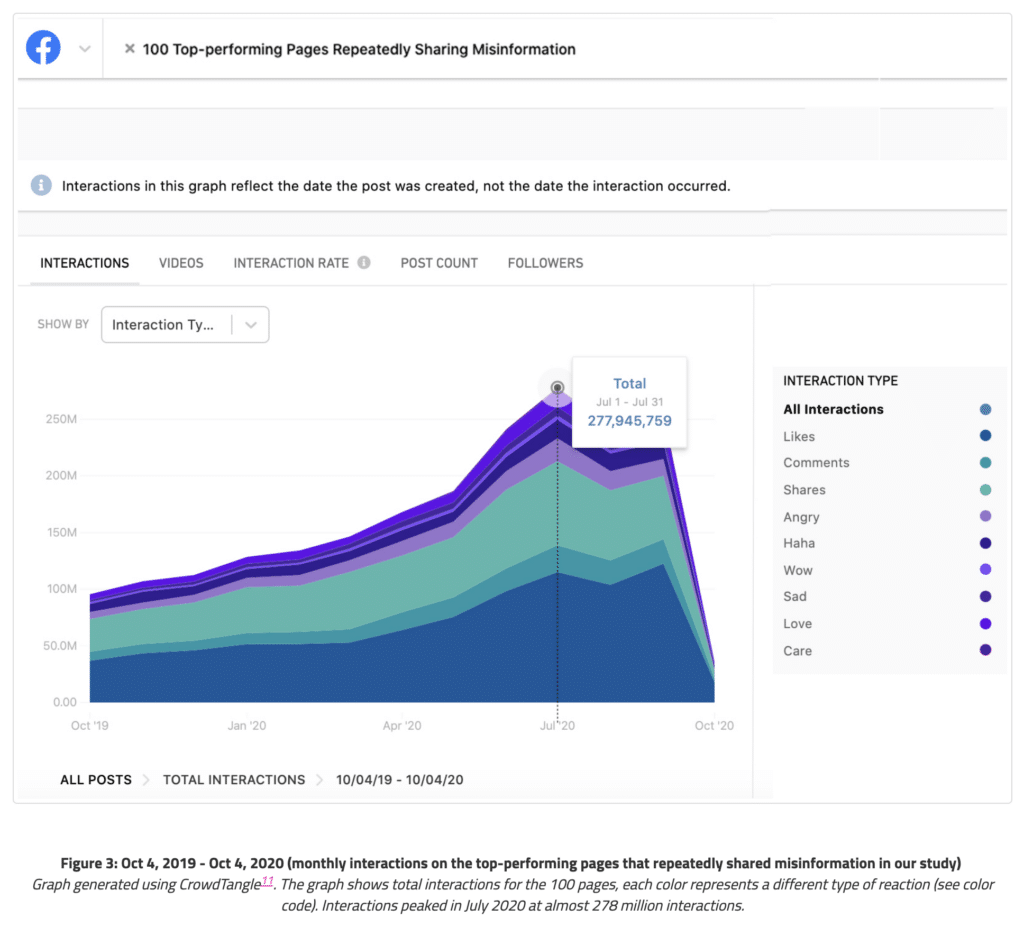

To be honest, the findings were terrifying when we put them together, because they're based on 15 months of research. The first was that Facebook could have prevented ~10 billion estimated views on the most prominent pages that repeatedly shared misinformation. That's just between March and October. Imagine if the platform had followed expert advice- it could have prevented tens of millions of people from seeing this type of content from these pages

The second big finding is that pages and groups that shared content glorifying violence, that were calling for attacks on law enforcement or attacks on people of color, that they had amassed over 32 million followers. The last big finding is that although Facebook promised to do more to fight misinformation, in 2020 the top misinformation posts were more viral than misinformation posts in 2019. Again, it just shows largely that Americans were pummeled by disinformation and Facebook could have stopped it- the solutions were there- and didn't.

Justin Hendrix:

I think one of the interesting things about this report is that you chronicle the moment that Facebook did decide to intervene and that moment then becomes your way in to analyze its prior response and what it did and didn't do. Explain how you found that, and when that happened, and what you observed happening on the platform.

Fadi Quran:

This was very exciting. I have to say, we kind of celebrated a little bit when we saw the down-ranking. These pages that were flooding Americans with misinformation, suddenly not being able to weaponize Facebook's algorithm.

So this is what happened. Facebook, early in 2018 actually, said that they were going to move to reduce the reach of pages and groups that repeatedly share misinformation and other types of borderline content.

The problem is, nobody had a way to measure whether Facebook was actually tweaking its algorithm or not. What we decided to do was, instead of playing whack-a-mole, just finding these posts or these bad actors and reporting to Facebook. We were going to use all of the fact-check content by independent fact-checkers and reverse engineer to see who are the main actors sharing all of that misinformation, then find the gaps in Facebook's policies and start pushing this content to Facebook to ensure that they downgrade those pages.

Of course, Avaaz wasn't the only one finding this content and sharing it. You had fact-checkers and a large civil society coalition that was pushing as well. At the end of September, we delivered a lot of this to Facebook and to fact-checkers.

We hit some sort of threshold it seems with Facebook, and we began seeing pages that were getting 700,000 interactions per week, a million interactions per week, suddenly just have their interactions, their reach collapse. The way we found out- Facebook didn't tell us by the way- we saw the pages beginning to complain about suddenly not being able to reach as many people.

We then used the data that we had to essentially say, "Okay, so now we can finally see that Facebook, with a lot of pressure from outside, will actually tweak its algorithms and reduce people's reach." But that happened in October. What would it have looked like if Facebook took this more seriously, when the pandemic started, say, in March?

Justin Hendrix:

What we see on the graphs and the charts that you've provided is just a cliff- a plunge in terms of the interaction on these various pages and groups that you were following. It looks like Facebook had the tools to contend with the worst of this stuff and just hadn't decided to use any of it until the last moment.

Fadi Quran:

Yeah. Or, they just don't understand how this information ecosystem works. We don't know. This is why one of our calls is an investigation of Facebook. The truth is, we don't know whether this is a systems failure, or whether it was an executive decision at the company not to proactively take these steps. What we do know, is that Facebook definitely had the power to take these steps.

We actually see two plunges, which I want to emphasize for everyone listening here. The first plunge was when Facebook began down-breaking specific pages that were sharing misinformation repeatedly, that were flagged by us. There's a second plunge that also happens where Facebook announced its Break Glass Policies, where they tweak the whole algorithm to increase essentially, what they call news ecosystem quality, NEQs.

Imagine this power. I mean, I think people really can't grasp this. You have a tech platform that can literally change the whole information ecosystem for seven out of 10 Americans that are using it, with a click of a button- and they do. This is the astounding thing, right? It's not just misinformation that's going viral. For example, the period after the murder of George Floyd up until August, you see that these pages that repeatedly share misinformation outperform the top 100 US media outlets on Facebook, CNN, MSNBC, so forth.

That's really scary too, because those pages- it's not that the misinformation sharers have more followers, the top media outlets have four to one in terms of followers, much more followers than the misinformation sharers.

Justin Hendrix:

You are a global organization and you, of course you work with the people in multiple different circumstances with regard to what governments they're underneath. In this report, you're calling for more government action. You have some very specific recommendations. You call for a kind of, I don't want to say a czar, but a kind of envoy to be appointed to look at disinformation as a national problem. You encourage more effort to coordinate with the EU. One of the criticisms that I see of this thinking is that you're inviting government to essentially take more of an active role in the information ecosystem. The fear is that potentially puts people in harm's way in nations where they can't necessarily trust their government. How do you answer that? Is there a difference in the way you think about the United States versus other nations that you operate in?

Fadi Quran:

That's an excellent question. What we're looking for is essentially that democracies regulate the harms caused by social media platforms. The best example I can give to this is, when you look at the Environmental Protection Agency, you see a clear harm- environmental harm. We saw that it was destroying societies and communities, and an agency was created with very restricted, but clear responsibilities in terms of how to protect peoples' health. They can audit companies. They can set certain standards.

The reason we call for President Biden to appoint a strong individual within the National Security Council to deal with and investigate the issue of disinformation, is we never want governments to be deciding what information is okay or not okay. But, we want someone- and we think democracies are best placed- to hold social media platforms accountable for the harms caused mainly by their algorithms.

The government should never be saying this, "This post is okay, this post is not okay." But the governments of democracies should definitely be saying, "Facebook, your algorithms should not be amplifying disinformation and making authoritative news sources lose money and shutting down journalism. That's not a fair use of algorithms, if we want a safe and healthy and equal society."

The one point I will say is, there's all this fear of the role governments can play in censoring speech, and they do. I'm from the Middle East. I see how governments can essentially censor speech and silence people. I also think we need to look at how social media platforms, by allowing censorship through noise, also sensor individuals and silence individuals. The goal here is to find the balance.

Imagine this power. I mean, I think people really can't grasp this. You have a tech platform that can literally change the whole information ecosystem for seven out of 10 Americans that are using it, with a click of a button- and they do. This is the astounding thing, right?

FADI QURAN, AVAAZ

Justin Hendrix:

So, you put this report out on the same week that Congress is about to haul Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey and Sundar Pichai into Congress to hear about January 6th and extremism and disinformation on their platforms. What are you hoping that Congress might be able to do?

Fadi Quran:

I think regulation is coming, whether we like it or not, and getting good regulation is going to require societal deliberation, kind of like what we're beginning to have now. I think we need to have more of these conversations, spending hours thinking about the details to get it right.

I think anyone claiming that we shouldn't be moving to regulate these big tech platforms, they're saying that they accept the totalitarian rule of Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey and Sundar Pichai on everything we say, because they're the individuals deciding.

It's not a freer marketplace of ideas right now. It's Zuckerberg's marketplace of ideas. I never got that argument of, we're inviting governments to get involved, unless the idea is that they trust someone like Mark Zuckerberg more than they would trust any elected official. I don't see why that should be the case, if that makes sense.

Justin Hendrix:

Ideally, democracies would be the engines of oversight. But even folks who watch these hearings very closely will tell you, the executives don't quite answer the questions. They never offer up the evidence that's requested of them, and they just wait it out. Congress doesn't have the resources to go up against the lawyers for these firms. It's tough.

Fadi Quran:

Yeah. I totally agree that it's tough, but I think we can push it the other way. It's going to be a struggle. I think we're all in this together. I think the trauma caused by the last four years, at least in the US, but for other communities, if you look at the Rohingya and other communities, that's one of the things that gives me hope is, we do see a movement growing across the globe of people who want to solve this issue. I think eventually, the moral universe is long, as they say, but it bends towards justice. I think we can win this battle here.

Justin Hendrix:

One thing that you do suggest is, that if lawmakers do move forward with a 9/11-style commission, that they should not just focus the investigation on what happened at Capitol Hill, but also on the social media companies. I have also argued exactly that, but right now it seems the prospects of a commission are fairly dim.

Fadi Quran:

We were hearing the same thing that you were hearing, which were that the chances of this were low. I have to say, after our report, we briefed about 17 Congressional offices, and the level of energy seems to be changing towards wanting some sort of investigation. So, I think there are certain members of Congress who want to push in this direction. My sense is there's still a possibility.

Hopefully, one of the questions that we are pushing to be asked at the hearing- and I know a bunch of experts including yourself have pushed similar questions- is about directly asking Facebook and the companies if they would allow an independent audit or investigation into their role. I think if that question is asked and the platforms don't provide a clear answer, it may kind of create more excitement.

Oftentimes, when you're doing a criminal investigation, you don't just look at who committed the murder, you also look at who sold them the gun and all the networks around them.

In this case, I think Congress would be remiss to just focus on President Trump and not focus on how he was empowered. President Trump is not going to be an outlier. He has shown that a certain form of politics is successful and that using tools like Facebook and Twitter can achieve huge gains.

Others who are potentially much smarter than him, much more effective than him will seek to use the same tools in the same ways and even better. That's why it's the only responsible thing to do, is to investigate how these tools were used on this front.

Justin Hendrix:

The 9/11 Commission looked at a range of questions around how our civilian travel infrastructure was turned against us. Questions around everything from building safety, through to immigration law. That was a broad perspective on all the aspects that came together into that attack. I think the commission on January 6th could similarly look at how our social media infrastructure was used against us in this way, or used against democracy in this way. I hope that even if a commission doesn't happen, that there'll be a substantial, congressional investigation that will get at some of those questions.

Are there any final details from the report that you have found that people are responding to, or that are stuck in your mind as most important?

Fadi Quran:

Yeah. Actually, before I move to that- to reaffirm a point that you just said, and I don't want to sound too extreme on this front, but I actually think that if social media platforms are not included in any investigation around what happened on January 6th, that could be a sign that the investigation is not about finding deeper solutions to heal America and fix democracy, but it's only a political stunt.

Because, if we want to get to the root of what's creating this polarization, what caused that violence and to prevent it from happening again, like you said, with 9/11, you have to look at all the different pieces of the puzzle. In this case, I would say social media platforms were a central piece of the puzzle.

Moving from that, to the question you just asked, there's a lot of details over the last 15 months and that we found and put in the report that we're not emphasizing, but one is, for example, ads. Facebook made a big deal about how it was going to stop misinformation in ads. Yet, we found a lot of that.

Another example's Facebook's AI. There's been a lot of controversy as you know, around Facebook's AI recently, but Facebook says, you know 98%, it always uses these big numbers. When we did the just random sample, we found that the AI was 42% ineffective in catching clones of exact pieces of misinformation.

For someone who reads the full report, I think the big picture is tha, we should never trust Facebook, grading its own homework. What it says about its AI, is kind of seems like they're not fully honest. What they say about their policies in terms of stopping misinformation and ads, seems dishonest.

I would even say that the report is very conservative. We downplayed some numbers. We kept them accurate, but we use the lowest estimates, instead of the higher estimates of the harm caused by Facebook. I think the problem is just much larger and their failure is much larger than any one civil society organization can measure.

Justin Hendrix:

Thank you.

Fadi Quran:

Thank you.

Editor's note: just prior to the publication of the Avaaz report, Facebook VP of Integrity Guy Rosen published a blog post on the actions Facebook takes to contend with misinformation, and after its publication a Facebook spokesperson disputed the report's methodology for determining the top line figure of 10 billion estimated views in response to a query from Casey Newton, who runs the newsletter Platformer.

Authors