Facebook Patent Shows How You May Be Exploited in the Metaverse

Elinor Carmi / Nov 18, 2021Dr. Elinor Carmi is a Lecturer in Media and Communication at the Sociology Department at City University, London, UK.

In his slickly produced yet notably awkward promotion video for Meta, Mark Zuckerberg set out a new vision for the company formerly known as Facebook. He emphasized that the new, virtual environment he intends to create-- the ‘metaverse’-- is all about the “feeling of the presence”. But while it was full of special effects, the video did not depict how our experiences in virtual reality will be shaped by commercial interests, and what will actually fund this ‘free’ environment Zuckerberg hopes we will all one day inhabit.

There is a reason why Zuckerberg did not come right out and say “in the metaverse, we run ads,” as he famously characterized Facebook’s business model in a Senate hearing in 2018. Instead, he focused on creating a fabricated relationship with users, where we are never shown what’s happening on the back-end of the company’s operations. But it is possible to get a sense of the virtual world Zuckerberg wants to build by looking at the company’s patents.

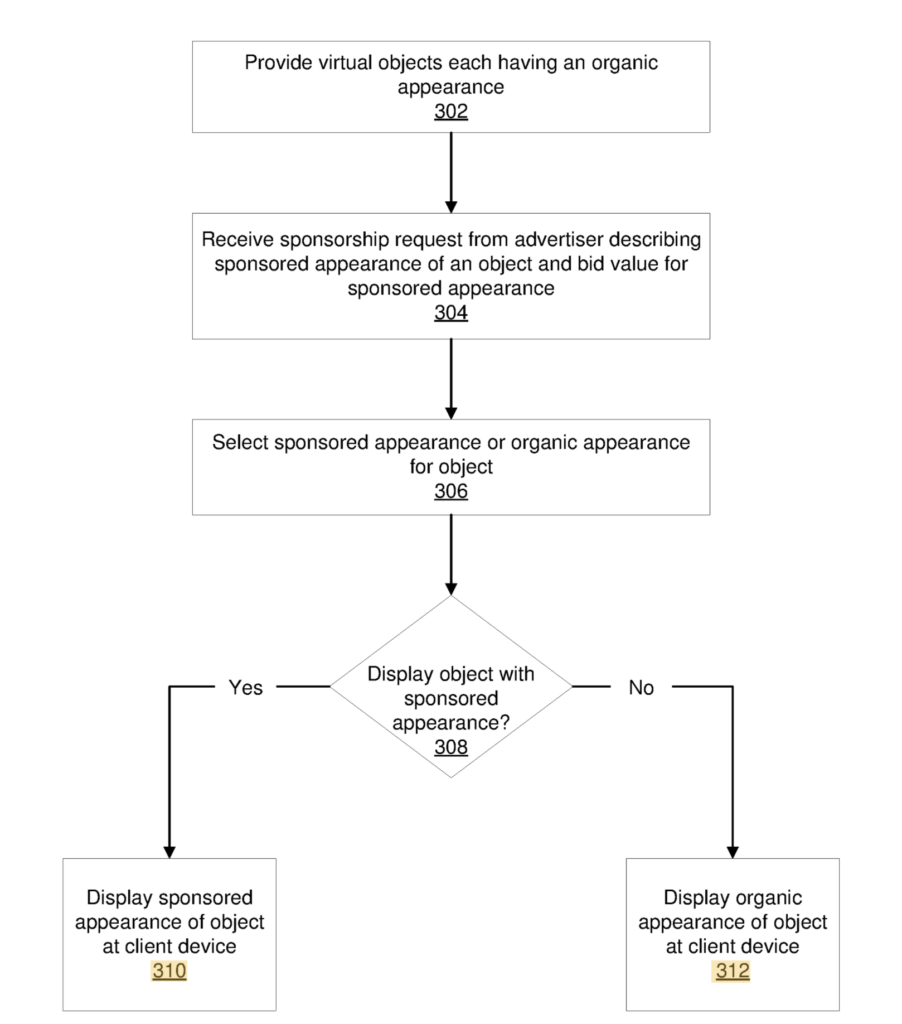

In a recently surfaced Facebook patent, we discover that, not surprisingly, Meta has designs to commercialize our virtual experiences and sell them to the highest bidder through further development of its ad auction system, employing real-time bidding. The patent makes clear that no matter how much Zuckerberg tries to convince legislators that the primary goal of the company is not simply increasing user engagement, it’s still the core motivation. Just like with Facebook, Meta will have the technology to alter the user’s experience according to what generates more engagement. “To increase user interaction with the virtual world, objects and locations presented in the virtual world may be customized for individual users of the online system,” as the patent reads.

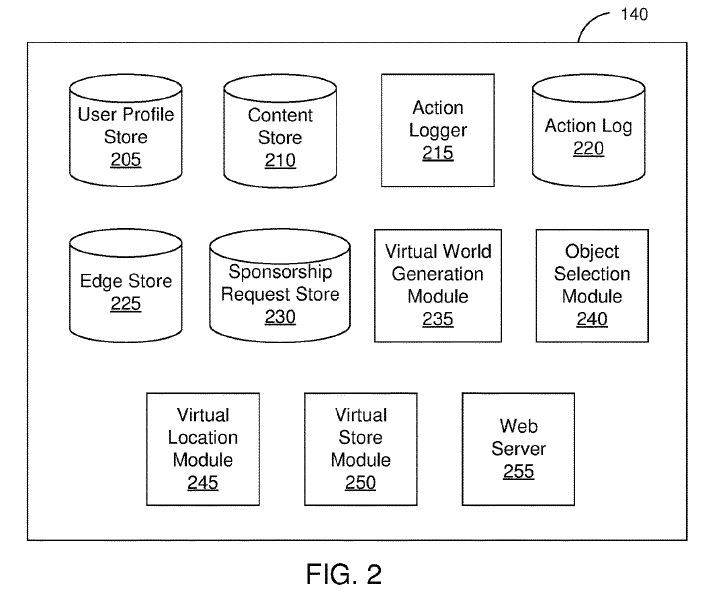

Not only that, in such a system advertisers will be able to bid over various objects to intervene in the user experience, through an evolution of Facebook’s ad auctioning system. Different actors will rely on Meta’s score of people’s Edges (Edge Store in the picture above) to know what is the probability that they will engage with an object, people or groups:

“The online system generates a score for an organic appearance of the object based on characteristics associated with the user (e.g., information in a user profile of the user, actions associated with the user profile of the user). In one embodiment, a score for the online system represents an affinity of the user to organic appearance, which provides an indication of the user’s likelihood of interacting with the object when presented using the organic appearance”.

This is similar to a previous feature Facebook developed called the Relevance Score. The company released the Relevance Score 2015 for advertisers to calculate how they expect a targeted audience might respond to an ad. When it comes to targeting people in this new real-time-bidding system, again, your actions outside the platforms can also be something companies bid for, including: using an app, joining or leaving a group, buying or reviewing a product, requesting info from a 3rd party system, and more. In other words, Meta is premised on enabling advertisers to buy access to our virtual experiences, creating a commercial presence and shaping what we see, and possibly even feel. This presence will rely on even further surveillance mechanisms, which along with the ones Facebook currently employs may also include advanced eye tracking technologies and biometric scanning of video selfies.

What does this mean for users? While Zuckerberg says he will ban micro-targeting of political and other ‘sensitive’ categories, we know that this was not true in the past, and the company also seems to still micro-target teens despite promises it would stop. But focusing on Zuckerberg’s reassurances diverts us from the broader picture, which is that Facebook’s business model relies on an exploitative, extractive business model whereby our everyday lives are rendered into quantifiable, transferrable data units that are ranked, scored and traded. Meta will make this intrusion into our lives even deeper. It’s about colonizing every last commodifiable data point Facebook can suck from us and turning it into something advertisers can monetize.

But as I say in a recent academic paper, the consent mechanism platforms like Facebook use as an indication that people agree to these procedures is flawed. Providing a feminist critique to the digital consent mechanism, I use four main feminist concept - process, network, embodiment and context - to show that the consent mechanism serves as an authorization tool for this exploitative business model.

For example, when we talk about process, the ecosystem Facebook offers produces two separate processes. One is fast and easy-to-use-- simply press the ‘I agree’ button (there isn’t a ‘I don’t agree button’). But if you wish to challenge the standard terms and conditions, expect a laborious fight. We recently saw that in the never-ending battle of the Austrian activist Max Schrems-- a founder of noyb-- against Facebook, the Irish Data Protection Authority argues that it is acceptable to put the consent mechanism under the ‘terms of use’, even though few people read or understand this language. One of the key problems is that we don’t really know what aspects of our behavior are extracted and how the resulting data and inferences can be used by multiple brokers. So how can we even exercise our rights when we don’t even understand what consent entails?

This leads to the next issue: embodiment. Companies like Facebook have managed to dehumanize us from the data that they extract from us. In our latest research around people’s data literacies, my research group found that most people don’t even know what data is. So it’s difficult for people to grasp that when companies talk about ‘data’ they are talking about users’ actions, behaviours, and preferences. As Facebook’s patent shows, people get Affinity Scores according to their relations with other people and things according to how frequently they interact with them: “A user’s affinity may be computed by the online system over time to approximate the user’s interest in an object, in a topic, or in another user in the online system based on the actions performed by the user”. In other words - people’s networks matter. So, a legal distinction between personal and non-personal data are not very useful here as people’s relations to their friends, colleagues, partners or even politicians is just as important. These data are not so easy to distinguish into separate boxes as regulators might like.

Finally, we don’t really know how data from one context is used in another. As Frances Haugen showed, demonstrating interest in health products or fashion topics can soon algorithmically escalate into being shown articles and products around anorexia and other dieting products. Just because I showed a picture of myself in a bikini to my friends doesn’t mean I want to get ads, articles or groups invites pushing unhealthy dieting products or super thin women. What will this dynamic be like in 3D virtual worlds?

While legislators across the world look to Haugen as an oracle about how the future of the big platforms should go, we need to listen to academics, activists, and lawyers from across the world to figure out how we create a reality to which we all agree. Various organizations, from Accountable Tech to the Norwegian Data Protection Authority, together with Amnesty, call for banning surveillance advertising models, recognizing them as harmful to our democracies and societies. Meta may mean a shiny new logo for Facebook, but the same exploitative business practices will remain, enabled by more advanced technologies in more complicated virtual environments. The time to push for policies that target these business practices is now.

Authors