Exploring Legal Approaches to Regulating Nonconsensual Deepfake Pornography

Kaylee Williams / May 15, 2023Kaylee Williams is a Ph.D. student of communications at the Columbia Journalism School.

Since the first significant wave of “deepfakes” in 2017, cybersecurity experts, journalists, and even politicians have been sounding the alarm about the potential dangers of digitally-generated video. The prevailing narrative surrounding these deceptive clips is that they might someday be weaponized by politically-motivated bad actors—such as authoritarian governments, domestic extremists, hackers, etc.—to defame political elites and undermine democracy in the process.

For example, in May 2019, when a digitally-altered video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi went viral on Facebook, news outlets were quick to catastrophize. “Fake videos could be the next big problem in the 2020 elections,” a CNBC headline read. “The 2020 campaigns aren't ready for deepfakes,” Axios echoed. In a House Intelligence Committee hearing held shortly after the video was debunked in the press, Representative Adam Schiff (D-CA) noted that this technology had “the capacity to disrupt entire campaigns, including that for the presidency.”

The problem with this popular understanding of the dangers of deepfakes is that it focuses almost solely on potential harms to the political sphere, and fails to acknowledge the reality (and severity) of the situation at hand. Contrary to popular belief, the vast majority of deepfake videos available online—approximately 96 percent, according to one 2019 study—are pornographic in nature; not political. More importantly, these explicit videos are almost always created and distributed online without the consent of the women (and it’s almost always women) they depict.

These videos constitute a form of image-based sexual abuse, and have been shown by several studies to contribute to adverse mental health outcomes for victims, including depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation. “Like other forms of nonconsensual pornography,” wrote legal scholars Mary Anne Franks and Ari Ezra Waldman in a 2019 piece for the Maryland Law Review, “digitally manipulated pornography turns individuals into objects of sexual entertainment against their will, causing intense distress, humiliation, and reputational injury.”

Despite the enormity of this problem, very few nations have enacted legal restrictions specifically pertaining to nonconsensual pornographic deepfakes (NPDs) or AI-generated pornographic media in general. Some countries, including Australia and Canada, have classified NPDs under the umbrella of nonconsensual pornography, which includes “revenge porn,” “up-skirt” images and other explicit content captured without the consent of the subject. But throughout much of the world, victims have essentially no legal recourse when their images are used against their wishes to generate pornographic videos. Four notable exceptions include the anticipated “Online Safety Bill” in the United Kingdom, a 2021 revision to the South Korean “Act on Special Cases Concerning the Punishment, Etc. of Sex Crimes,” California’s Assembly Bill 602, and Virginia House Bill No. 2678.

In this report, I outline and compare these regulations prohibiting NPDs, and provide recommendations for governments that wish to design their own anti-NPD laws. First, I provide non-technical background information on deepfake pornography and its impacts on nonconsenting subjects. Then, I conduct an examination and comparison of the existing legal restrictions on NPDs across the three countries mentioned above. I conclude with recommendations for lawmakers, including common mistakes to avoid when regulating NPDs.

Origins, Prominence and Consequences of Nonconsensual Pornographic Deepfakes (NPDs)

Journalist Samantha Cole reports that the software required to produce high-quality, realistic-looking deepfakes was first popularized by a small group of anonymous Reddit users looking to superimpose the faces of celebrities onto the bodies of adult film actors in pornographic videos. As a result, some of the earliest victims of nonconsensual pornographic deepfakes included A-list stars like Gal Gadot, Scarlett Johansson, and Taylor Swift.

Deepfakes of this nature are typically generated using artificial intelligence software trained on large quantities of still images of a single person’s face. The greater the number of high-quality images that are fed into the AI, the more realistic the resulting deepfake will be. This requirement also contributed to the initial popularity of celebrity deepfakes, since high-resolution pictures of A-listers tend to be relatively easy to find and download online.

Cole’s work shows that shortly after the deepfake enthusiasts on Reddit mastered celebrity NPDs, they began sharing tips and tricks for generating deepfakes from smaller photosets, so that they could make NPDs of people they know in real life, including friends, former classmates, and coworkers. This history highlights the fact that deepfakes have always been used as a tool of sexual exploitation, including long before they were identified as a potential tool of political disinformation.

Today, the software tools required to generate believable deepfakes have been packaged into a variety of publicly available, consumer-facing applications, and supercharged by new so-called "generative AI" models. “What we've seen over the last four years is the technology has gotten easier and easier from a user experience perspective,” said Karen Hao, the Senior AI Editor at MIT Technology Review, in an interview with New York Public Radio. “You literally just have to push a button to do the same face-swapping.”

The specific group of deepfake innovators Cole reported on were eventually banned from Reddit in 2018, but in the years since, a wider community of deepfake viewers, creators, and enthusiasts has continued to grow on other platforms. As a result, many forums and websites dedicated to the creation and sharing of deepfake pornography still exist online today. NPDs can also be found on many of the most popular pornography websites, including Pornhub.

The single most widely cited study on the prevalence of NPDs was conducted in 2019 by Deeptrace, an Amsterdam-based deep learning research firm, on behalf of Sensity AI, a deepfake detection company. In the study, Deeptrace estimated the total number of deepfakes (pornographic or otherwise) available on the open internet at the time to be roughly 15,000. They also estimated that the number of deepfakes was “rapidly increasing,” given that their count had doubled since 2018. As previously mentioned, Deeptrace found that 96 percent of those deepfake videos were pornographic, and likely created without the consent of the person depicted.

Furthermore, the authors point out that every single NPD they observed specifically portrayed female subjects. As a result, the authors concluded: “Deepfake pornography is a phenomenon that exclusively targets and harms women.” This fact is especially disturbing when considering the potential consequences—emotional, reputational, relational, or otherwise—of being digitally inserted into pornographic material against one’s will. Although few studies have explored the individual harms caused by NPDs specifically, there is a large body of evidence suggesting that victims of any form of image-based sexual abuse are more likely than non-victims to report adverse mental health consequences like posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, as well as challenges keeping or maintaining meaningful employment after being victimized.

The emotional harms caused by NPDs are also well documented in journalistic reports. “Every time you go to a job interview, you might have to confront and answer for this pornographic image of you that you never even knew existed,” explained Hao. “Every time you go on a date, you have to answer to the person that you're dating. And there already been multiple cases of women that have been harassed with rape and death threats because the public doesn't know that they're not real.”

More recent research conducted by journalist Jennifer Savin showed that Sensity’s projections as to the overall size of the NPD market may have been too conservative. According to Savin, Google searches for “deepfake porn” returned more than 57 million web pages in October, 2022. Furthermore, the Savin writes, “[web] search interest has increased 31% in the past year and shows no signs of slowing.”

Nonconsensual deepfake pornography differs from other uses of deepfake technology because these videos are not necessarily intended to deceive the viewer about their synthetic provenance—unlike the 2019 Nancy Pelosi video, for example. In fact, NPDs are most often labeled and advertised as deepfakes, and typically listed next to other algorithmic or AI-generated pornography online. This is because NPDs are, for the most part, created and shared for the purposes of sexual gratification, rather than emotional manipulation or defamation. This fact also serves as the key distinction between NPDs and “revenge porn,” and will be relevant to the discussion of whether the creators always intend to defame, harass, or otherwise harm the people they insert into NPDs.

Lee So-eun, a senior researcher at the Korea Press Foundation’s Media Research Center, expanded on this point in an interview with Korea JoongAng Daily, saying, “Deepfakes are problematic not only because they twist the truth and steal other people’s identity, but because they amplify a certain emotional effect…People objectify a person that they have admired and put them in situations that would otherwise be impossible—against their will—and use those videos for their pleasure, which can be quite problematic morally and ethically.” This important difference requires that NPDs be addressed separately from revenge porn within the law.

Legal Approaches to the Regulation of Nonconsensual Deepfake Pornography in Free Speech Countries

In various writings and interviews, University of Miami Professor Mary Anne Franks argues that many national governments—and particularly that of the United States—have made the mistake of assuming that false and harmful speech (including the creation of deepfakes and other inauthentic media) is best mitigated with counterspeech, rather than regulation or limitations on the marketplace of ideas, which may inadvertently silence dissenting voices. “Whatever merit these claims may have had in the past, they cannot be sustained in the digital age,” Franks wrote in 2019. In fact, she continues:

It is the failure to regulate deep-fake pornography—not the efforts to do so—that most seriously undermines the free speech rights of vulnerable groups. To do nothing about harmful speech in the digital age is far from liberal nonintervention; rather, it is a normative choice that perpetuates the power of entrenched majorities against vulnerable minorities.

As such, it is imperative that governments develop and enact proactive policies which adequately shield victims from being portrayed in sexually explicit content without their consent, and treat the creation and sharing of NPDs as a criminal act.

To their credit, several nations including Canada and Australia have sought to regulate NPDs using existing legal restrictions on nonconsensual pornography. However, this approach does not go far enough to shield victims in countries where citizens enjoy freedom of speech. This is because, according to Danielle Citron, a law professor at the University of Virginia, deepfake videos have historically been considered a form of “artistic expression,” and have therefore been shielded from legal scrutiny. Others have likened NPDs to “fan fiction,” given the creators’ frequent depictions of celebrities. As such, governments must adopt legal frameworks that specifically target NPDs as a form of sexual abuse if they hope to slow their creation and spread online.

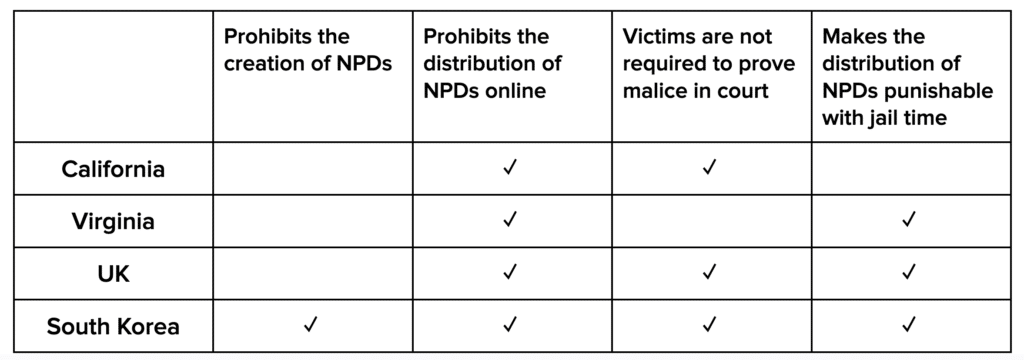

Here, I examine four laws which do just that, identifying several notable characteristics amongst them, which are summarized in Table 1. Together, these laws represent some of the earliest attempts by democratic governments to restrict NPDs online.

This analysis does not represent a comprehensive list of the existing or proposed laws globally which pertain to NPDs. China, for example, has adopted one of the world’s most restrictive anti-NPD laws. However, because I am specifically interested in examining legal frameworks within countries which typically protect citizens’ rights to free speech, I opted not to examine laws adopted by nations without those protections.

The American Approach: A Messy, Incoherent Patchwork

In the United States, there are currently no federal legal protections for victims of this kind of image-based sexual abuse. And while most states currently have laws on the books prohibiting nonconsensual pornography, only a handful of states—including California and Virginia—have introduced legal language specifically targeting NPDs. While these laws are certainly better than nothing, both contain fatal flaws that prevent them from sufficiently protecting victims.

In 2019, the California state assembly passed AB 602, which allows victims to sue anyone who shares an NPD of them online, given that “the person knows or reasonably should have known the depicted individual did not consent to its creation or disclosure.” There are several drawbacks to this approach. First, and most importantly, while this framework offers a private right of civil action under which victims can seek monetary damages, it does not actually criminalize the sharing of NPDs. As a result, perpetrators cannot be fined or jailed under this law. As such, the law presents only a financial disincentive toward the sharing of NPDs, as opposed to a criminal one. Secondly, the requirement that the perpetrator “know or reasonably should have known” that the NPD was created without the consent of the subject leaves far too much ambiguity for adequate enforcement of the law. Those accused of circulating NPDs online could very easily claim ignorance of their provenance, and argue that they had no way of knowing that the media was created without the consent of the subject. This defense would be incredibly difficult for the plaintiff to disprove in court.

Finally, the law fails to restrict the actual creation of NPDs, therefore allowing Californians to digitally insert others into pornographic content against their will so long as the content is never shared. It is possible that the legislators excluded this aspect from the bill in an effort to avoid legal challenges on the basis of the First Amendment, or as an attempt to be as minimally restrictive of private behavior as possible. Either way, the result is a devastating oversight. The failure to prohibit the creation of deepfake pornography without the express consent of the subject limits victims’ legal recourse outside of particularly devastating cases. To give a hypothetical example, if a victim were to discover that a coworker or neighbor had created several NPDs of them for his own entertainment, that victim would have no legal recourse under the California law unless and until the perpetrator shared them online.

Also in 2019, the Commonwealth of Virginia also passed its own anti-NPD law, which is more severe than the California one, but also more difficult to apply. Unlike the California law, Virginia House Bill No. 2678 amends an existing penal code related to revenge porn in order to include language which prohibits the sharing of “falsely created videographic or still images.” This means that in Virginia, the sharing of NPDs is considered a Class 1 misdemeanor, punishable by up to 12 months in jail.

However, the Virginia law only prohibits the sharing of NPDs in cases where they are intended to “coerce, harass, or intimidate” the person depicted. This is a shortcoming which arguably renders the regulation useless in many—if not most—cases, because it requires that victims be able to prove in court that the perpetrator acted maliciously when they shared the explicit content. As I mentioned in a previous section, prevailing anecdotal evidence has shown that while pornographic deepfakes are occasionally used to blackmail, defame, or manipulate the women they depict, they are much more often created and shared for the purposes of sexual gratification, unbeknownst to the victim. Under the current legal framework in Virginia, a defendant could reasonably argue in court that they created and shared an NPD simply out of “admiration” for the subject, and with no intention of harassing or intimidating them. By doing so convincingly, they could successfully avoid jail time under this Virginia statute.

Lastly, the Virginia law also fails to prohibit the creation of NPDs, much like the California one.

UK’s Online Safety Bill: Punishing Harms, not Malice

In November 2022, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Justice announced that an amendment to HL Bill 87, known as the “Online Safety Bill,” would include language that criminalizes the posting or sharing of NPDs as part of an apparent crackdown on “abuse of intimate images.” According to a press release published alongside the announcement, “The amendment to the Online Safety Bill will broaden the scope of current intimate image offenses, so that more perpetrators will face prosecution and potentially time in jail.” Close examination of the text of the amendment reveals that NPDs will be legally defined as “manufactured intimate images.” Under this new law, people convicted of sharing NPDs will face a minimum of two years in jail.

Unlike the Virginia law, the Online Safety Bill does not require that the perpetrator intend to cause distress or humiliation by sharing the NPD(s). The mere act of sharing them is enough. This means that victims will not be asked to prove malice in court, and reflects the overall philosophy behind the Online Safety Bill, which seeks to offer legal recourse to victims of online harm regardless of the intentions or motivations of the people who caused that harm.

Much like the previous two laws, the Online Safety Bill’s main drawback is that it does not restrict the creation of NPDs for personal consumption. Given this fact, it should be expected that online forums dedicated to the technical aspects of NPD creation and discussing tips and tricks for making them more realistic will continue to be popular in the UK, as well as California and Virginia.

The Online Safety Bill is currently being debated in the House of Lords, and is expected to pass and be enacted this year.

South Korea: The Gold Standard for NPD Regulation

In 2020, the South Korean government enacted a revision of the “Act on Special Cases Concerning the Punishment, Etc. of Sex Crimes” which prohibits both the creation and distribution of “false video products” which “may cause sexual desire or shame against the will of the person who is subject to video.” Under this new law, those convicted of NPD distribution can be punished with up to five years in prison. If the perpetrator sold access to the NPD(s) for a profit, they could be jailed for up to 12 years.

Importantly, this Korean law requires no malice or intention of harm on the part of the NPD creator, and expressly prohibits the creation of NPDs for the purposes of sexual gratification, as well as defamation. This means that when these cases are tried in court, the victims do not need to prove that they were harmed by the creation of the NPDs, only that they exist at all. Conversely, this also prevents perpetrators from arguing that they created or shared the media out of “admiration” for the subject, as opposed to an attempt at humiliation or defamation. As such, this is the most comprehensive and advantageous legal approach to NPDs among those I have highlighted in this report, and should therefore be considered the gold standard for the national regulation of NPDs.

It is worth noting that several factors unique to South Korea may have contributed to the decision to adopt such a restrictive law. First, journalistic reporting has shown that deepfake creators tend to target female K-pop singers more often than celebrities of other nationalities. In fact, according to Deeptrace, roughly 25 percent of all NPDs feature Korean female K-pop stars. In addition, this policy was proposed in the wake of an extremely widespread incident involving digital image-based sexual abuse within the country. “The Nth room case,” as it is now known, involved a group of anonymous Telegram users who targeted hundreds of women and dozens of minors with horrific acts of sexual violence, including rape and physical assault as well as the creation of NPDs and other forms of nonconsensual pornography. This incident marked a watershed moment for the South Korean government’s approach to digital sex crimes, and inspired a large overhaul of the nation’s penal code.

Analysis & Recommendations

While AI experts, politicians and journalists have been busy wringing their hands about potentially nefarious uses of deepfakes and generative AI in the political arena, women all over the world have been suffering the consequences of the use of these technologies for years, typically with very little attention from the mass media or support from national governments.

Policymakers should design regulations to prevent NPD creators from objectifying and violating others against their will, and, to the extent possible, emulate the South Korean approach. Informed by the horrific crimes committed during the Nth Room Case, South Korea’s law correctly regards the creation and distribution of NPDs as an extremely serious violation of victims’ rights to privacy and overall well-being, and seeks to slow the proliferation of NPDs by applying significant legal consequences for those who violate the law.

In order to best protect victims from the emotional and reputational harms caused by NPDs, legal restrictions should include these three key features of the Korean law:

- They must prohibit the creation of NPDs, as well as their distribution.

- They must not require malicious intent on the part of the perpetrator.

- They must make violations of the law punishable with imprisonment.

Without even one of these features, any anti-NPD law is destined to be unenforceable, toothless, and thus essentially useless from the perspective of victims.

And while the larger question of whether and how to best regulate generative AI altogether lies decidedly outside of the scope of this report, I would encourage policymakers to consider NPDs the tip of the digital sexual abuse iceberg. As AI tools become more sophisticated and easily accessible, we will see further innovation in the realm of digitally-generated pornography, which will undoubtedly make the detection and prosecution of crimes more difficult in the future.

Authors