Evaluating the Efficacy of the Term "Infodemic"

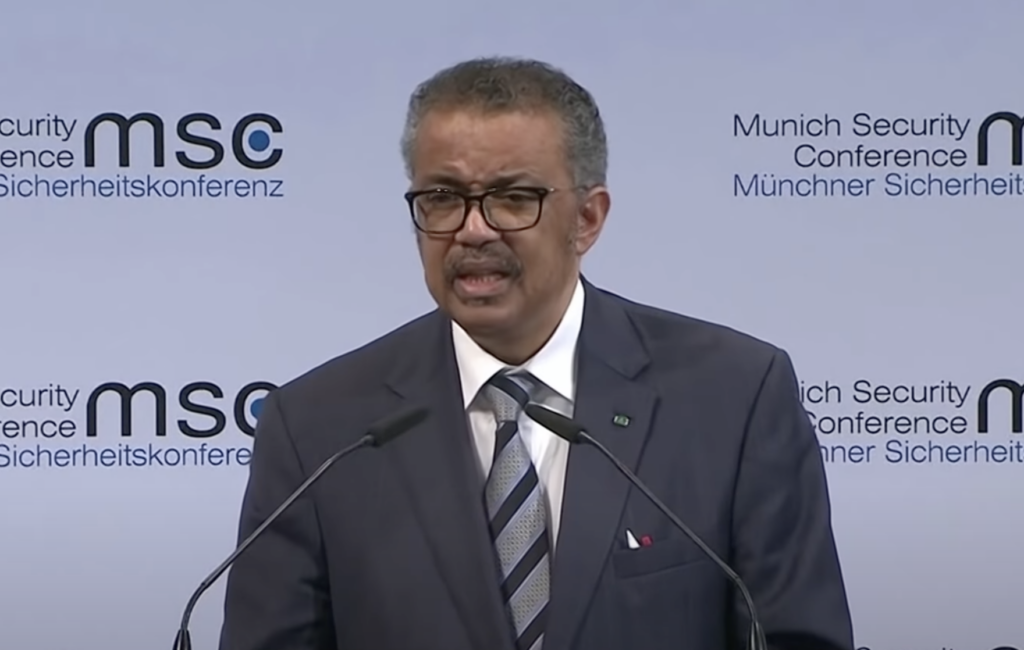

Justin Hendrix / Aug 9, 2021Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the World Health Organization, began to raise the alarm about false information about the virus, including phony prevention measures and other rumors that he said were potentially harmful to public health. “We're not just fighting a pandemic; we're fighting an infodemic,” he said.

The World Health Organization then went on to make an infomercial about the term. Over an animation, a narrator says "an infodemic is an excessive amount of information about a problem, making it difficult to identify a solution. During a health emergency, an infodemic can drown out reliable information and allow rumors to spread more easily, impeding an effective public health response."

The term has now been widely adopted in the news media, employed as an organizing idea for dozens of academic and think tank panel discussions about mis- and disinformation, and cited in the academic papers. But where did the term come from? And is it useful?

To explore these questions, Tech Policy Press spoke to Chico Camargo, a lecturer in computer science at the University of Exeter in the UK and a research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford; and Felix Simon, a doctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, a research assistant at Rice Institute for the Study of Journalism, and a Knight News Innovation Fellow at the Tow Center at London University. Camargo and Simon just authored a paper. Autopsy of a Metaphor: The Origins, Use and Blind Spots of the Infodemic, which was published in late July. Below is a lightly edited version of the discussion.

Justin Hendrix:

We're going to talk about this term infodemic in this paper that you've put together around it, which I found very interesting. First, just start a little bit with why you took up this challenge, why you decided to delve into the background of this term and what its history is.

Chico Camargo:

So it's funny. This conversation between Felix and I started actually on Twitter. We were just both ranting about the same thing at the same time. And Felix comes from a more journalism-like background and I come from a very STEM heavy background, a lot of people doing computer science and physics and maths. And we were both ranting about this term infodemic being sort of a loose catch-all umbrella thing for any spread of concerning information during the pandemic. And the reason I'm saying concerning is because of this umbrella catchall term. We had both noticed that there were people using the term infodemic to refer to wrong information about COVID-19, things like drinking tea cures the disease, but also some people were using it to talk about anyone posting things online, or to talk about how there's a lot of news today.

And it feels like there's some overabundance of information. People were just using this term so loosely. And we both felt that our concern wasn't just academic pettiness, but rather that this was a bit concerning, kind of like how terms like fake news can be weaponized, can be used to feed some notion that there is a crisis and governments need to act and that can all be very dangerous and we decided to stop ranting about in Twitter and to actually write something together, thinking hard about these issues. That's how it started.

Justin Hendrix:

Tell me a little bit about the history of the term, because you trace it back to actually interestingly David Rothkopf, who first used the term I think in 2003, or the earliest instance of it that you were able to find.

Felix Simon:

Yeah, I think that's correct. And we basically remember directly he coined it in the Washington Post op-ed. Again, If I remember correctly around the outbreak of the first SARS epidemic at the time, and it was interesting because after we had published the academic paper, David actually got some touch with us and we had this interesting little conversation where he briefly spoke about the term, what he had intended with it and it was basically very limited. He didn't mean for it to go overboard and turn into this current thing that we're seeing online. And it's interesting because basically when David Rothkopf coined the term back in 2003, it was lightly used afterwards.

So you had a couple of entries on the scholar with various papers that I'm picking up and you had some news coverage boost. It didn't really took off like other terms. And then suddenly getting to 2020 when the WHO used and it, it's the first time, one of the situation reports and it was then subsequently picked up by the Director General and other people back at a point when it really took off and when lots of journalists, academics, policymakers, all these different groups, civil society started jumping on the term and started using it for their various purposes as Chico has explained.

Justin Hendrix:

So certainly in the last year and a half or two years since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, I can't tell you the number of panels I've seen, the number of articles and certainly even testimony on Capitol Hill in the United States where the term infodemic has been invoked. What do you see as the dangers of the use of this term in the present moment?

Chico Camargo:

I feel like the dangers they happen in two spheres. One is in the people who are actually trying to develop an understanding of what's going on. So then you have a lot of researchers who are actually trying to understand how information spreads online and its consequences. And you see today when you look at papers using that word, that there is almost no agreed on definition and it feels like a massive bandwagon. I'm not saying there's no good research about it. There is, but there's also a million papers that are completely unrelated and just using the most fashionable terms at the time. But that's a concern that really mostly matters for academics, and for researchers. The bigger concern here is that a term like that is as you mentioned, being used in places like governments, and used as a very quick way to summarize concerning things happening today as wild spread of misinformation and its consequences for public health.

Yeah, I get it. It is a good term for summarizing things. Of course, that's the reason why it's being used. But there have been already multiple countries. We cite a paper that mentions 18 of them, I'm sure there's more today, countries that have created imposed or passed new regulation to tackle the spread of misinformation. And sometimes that means giving the president or prime minister the right to put anyone in jail. Anyone who is, according to the government, spreading misinformation. Or the right to pass new legislation and approve new budgets without speaking to the Congress in that particular country. That has happened in so many countries and having a infodemic crisis that is validated by academics and journalists and policy makers, becomes like a free pass for anyone, any government to say, "Well, it's a crisis, we need to jump into a state of emergency", and that is our biggest concern here. That's why when we end the paper, we say, "Folks, please let's slow down and be more rigorous because this can have serious real world consequences."

Felix Simon:

I think a big problem is also the feedback loop between the worlds of academia and journalism and policymaking. So if you have a term that is validated by scientists and then picked up journalist instead spun further and further, will of course end up in the halls of policymaking world of Congress and the UK parliament and the [inaudible 00:10:03], and all these people they don't have a lot of time. So they have a tendency to go towards these things which are easy to understand and easy to grasp in which you can use and apply. And that's one of the things we still do for infodemic. And of course this paper by Roxana Radu, who is actually a colleague of ours at the University of Oxford where she demonstrated that it's very easy with these terms, they can be exploited by authoritarian minded governments to then push through laws, which are infringing upon human rights, which could torn things like freedom of speech and freedom of expression. And that was something we really worried about.

Of course, it's always an issue of academic sketch into something. Cause there's a lot of buzz around it. That will always happen. That's fine to some extent, everyone does it. It's not our major concern. It's more the unintended consequences of such a scientifically validated or seemingly scientifically validated concept, which we were quite concerned about.

Justin Hendrix:

You do give a nod to the idea that the term, even though it is umbrella and imprecise could potentially be useful in spurring some positive action and in coordination and collaboration that people maybe see in it, a call to action, that's useful. What do you think folks should be doing around the problem of disinformation more broadly and perhaps information overload as a separate kind of category of concern.

Felix Simon:

In my brief answer would be listen to the communication researchers. Who've done a lot of work not just in recent years, but recent decades, actually these problems, these issues, and look at the evidence to support them and producing good evidence based research. Because if you go one step further, if you go away from the hype and away from the people, they're either saying there's no problem at all or the people are saying, we're sort of facing, doom and the apocalypse. There's are a lot of gray between lots of decent researchers come out recently to come to sciences, from communication scientists, from journalism scholars, which demonstrates for instance, that information abundance, It is to some extent a thing. But the question is always then where do you draw the benchmark? How much information is too much information? And the question is, is it actually a problem for many people? Of course there's always situations where people feel overwhelmed by information. I feel overwhelmed by information at times, but at the same time, we've all developed processes of how to deal with that.

So we selected the turn off to certain things, we have stopped reading the news for a couple of days, and then we'll be fine again. And if you look at the actual evidence, if you look at how people deal with information, how they process it, and a lot of that actually undermines these frames of the information apocalypse being around the corner. And I think that would be my big, please listen to the scientists and support the research, which tries to make good evidence-based case for what is happening.

Chico Camargo:

One of the main messages, and it's probably the last line of the paper, we also wrote a shorter version of it. More like a blog post that was posted on the Oxford Internet Institute website. The final, the bottom line is that it's probably worth sacrificing a few catchy headlines. If that means doing better science, better policy making, not allowing more governments to concentrate power by claiming some kind of crisis. You know, instead of saying "there is a wild infodemic spreading over the world, booh!", we can probably say something slightly more accurate with, you know, still reaching out to people, but bringing more precise and less hyped up information. It's probably worth sacrificing a few headlines.

Justin Hendrix:

After you published your paper, the Surgeon General of the United States issued a report on misinformation around the COVID-19 vaccine and its effect on the pandemic here, having done this work and then having sort of seen that announcement, how did you assess his perspective?

Chico Camargo:

Yeah, indeed that came right after we published it. I overall don't mind. It's funny, but we aren't actually not that first about the word itself, you could call it infodemic. It could call it banana. It doesn't matter. It's not about the word. It's about how it's used. If the word is just a kind of placeholder term to validate whatever a government is thinking, which is usually how these words are used, then we should really just focus on what the actions are going to be. Often the word infodemic in this thinking of information as something that spreads like a virus, often, it sort of assumes that information is going to spread any way and there's nothing we can do about it. There's no one behind it.

Whereas actually often there is money invested to make these things happen overall. My concern is often not in what, in this case, the government is saying about the infodemic itself, but in what measures they're proposing to tackle it. If someone says there's an infodemic, but then they propose a lot of things that are good, that respect people, that do not put freedom of the press in danger or anything like that, then sure. Then I'm okay with letting people calling it an infodemic. That's really not what we're concerned about here.

Justin Hendrix:

So you're not the word police, but just are arguing more for specificity and precision in the way that we apply this term.

Chico Camargo:

Exactly. We're just saying, guys, please don't jump on the bandwagon, but if let's say 10 years from now, there is the big discipline of infodemics and that has actually contributed to a lot of good things in the world, it's okay if it's called informatics, that's fine.

Justin Hendrix:

Felix and Chico. Thank you very much.

Felix Simon:

Thank you for your time.

Chico Camargo:

Thank you.

Authors