Europe Gets Tough on Influencers

Clara Riedenstein / May 30, 2024

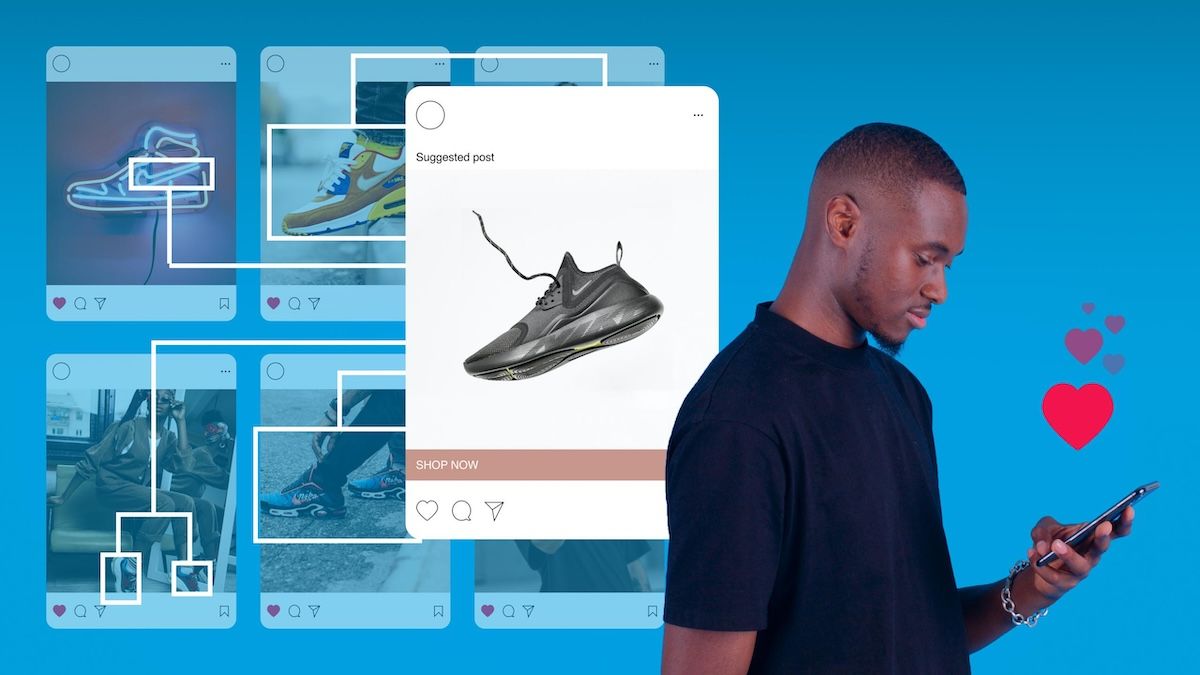

Image by Comuzi / © BBC / Better Images of AI / Likes / CC-BY 4.0

Kids once dreamed of becoming singers, astronauts, and actors. Today, they may want to become influencers. A 2019 survey found that 30% of children aged 8-12 in the US and the UK want to become YouTubers, triple the number of those wanting to explore space for a living. “Influencing” as a profession is on the rise: it is estimated to become a $70 billion industry by 2029. Despite its popularity, it has remained largely unregulated to date. This may soon change.

“Influencing” is synonymous with social media fame, glamor, and quick money. In Europe, it might soon be synonymous with a lot of unglamorous paperwork and hefty fines, too. Europe is out to hold influencers accountable for their—well—influence. Under the Belgian Presidency, the European Council is calling for stricter EU-wide influencer regulation. This would involve harmonizing national rules, improving the enforcement of existing laws, and creating new influencer-specific regulations. The proposal is the latest in a series of legislative proposals in Europe. France passed a new regulation for content creators in 2023, and Italy proposed its own influencer law later that year.

Dubbed the marketing firms of the future, influencers sell products by promising a new life to consumers. And like all advertisers, influencers have to abide by existing advertisement and consumer protection laws everywhere. They are obligated to clearly signal any advertisement as such and are banned from promoting certain harmful products. Despite these existing rules, enforcement has been patchy. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released guidelines for influencers in 2019, but largely limits its enforcement and fines to companies, rather than influencers. A 2020 study revealed that three-quarters of influencers are flouting these guidelines, deliberately hiding the disclaimers such as the #ad in their posts.

In Europe, there is a striking lack of compliance, too. An investigation by the French consumer protection authority revealed that 6 in 10 influencers were not complying with existing regulations. In addition, there have been a number of prominent scandals involving influencers. For example, Italian influencer Chiara Ferragni was fined €1mn for falsely claiming to her 30 million Instagram followers that the proceeds for purchasing a designer pandoro cake would go to funding a children’s hospital.

Several countries cracked down as a result. At the end of 2021, Belgium and its regional Flemish government established specific guidelines for influencers based on existing consumer and advertising law. These include, for example, the requirement for influencers to list their address in their bios. The requirement sparked controversy, with many content creators arguing it violated their privacy.

France went further, establishing a new law that provided the first legal definition of influencers: individuals who, “for a fee, engage their audience with their renown.” That means, regardless of whether someone has 300 or 3 million followers, as long as they get money or free stuff, the law considers them an influencer. Designated influencers also have to adhere to new stringent rules, including the requirement for a formal written contract that specifies remuneration terms and identifies all involved parties. Finally, they are prohibited from advertising certain products and have to indicate where beauty-enhancing filters have been used in their posts.

Influencers are similar to marketing firms in some ways and very different in others. For one, influencers are usually a one-man (more often a one-woman) show. They do not have the same amount of time and resources to spend on compliance. Most don’t even “influence” full-time or make much money doing it (if any). A 2022 LinkTree report found that most influencers do not consider themselves full professionals. The average influencer has 1-10 thousand followers and sometimes gets gifts from brands in the form of free clothes, creams, or trips. Complying with regulations would likely cost them more than they would make through their online activities, involving legal costs and complicated paperwork. These costs could skyrocket if fined for violating even a minor regulation.

Spain’s new influencer law, acknowledging these factors, only applies to content creators with significant “influence.” An influencer is only subject to the most stringent rules if they make over half a million Euros per year and have over 2 million followers. Less stringent laws apply if an influencer makes over 100,000 Euros and has a similar amount of followers. Italy’s recent law follows a similar structure.

These differences in regulation among countries mean some influencers feel disadvantaged. A Belgian part-time content creator interviewed for this piece said she had lost two brand deals because she entered into a legal dispute with the government over ad signaling on her posts. “If I have to take down my posts, brands will just go to an influencer in the US or elsewhere in Europe where rules and enforcement are not as tough,” she explained.

A unified EU-level law could mitigate these issues by standardizing regulations and enforcement across the continent, ensuring that Belgian influencers do not feel disadvantaged compared to their Spanish counterparts. They would continue to feel disadvantaged toward American influencers, though, where rules are more lax and enforcement is less stringent.

Consumers will benefit from the new rules. Increased transparency, stronger guardrails, and protections for younger consumers will lead to more trust in influencers and the brands they support. For example, indicating where filters and Photoshop have been used may have a positive effect on teenagers’ mental health, a common concern for policymakers today.

Regulation will also lead to a more coordinated response from industry. There is a push to ensure influencers are aware of existing regulations. Last week, the European Council published a report acknowledging the need for more support to help influencers to comply with the new regulations. New organizations representing content creators and online marketing are popping up, such as the Influencer Marketing Trade Body (IMTB) in the UK, which is now creating a pan-European alliance with members across the EU. There is talk of permanent influencer representation in Brussels if the Council proposal pushes ahead. Soon, going viral on TikTok could not just mean free creams and serums, but also lobbying in the European Parliament.

Authors