Election Meddling, Censorship, and More Bad News in 2024 Freedom on the Net Report

Justin Hendrix / Oct 16, 2024Audio of the podcast discussion included below is available via your favorite podcast service.

Caracas, Venezuela, August 28, 2024: An opposition demonstration led by the Maria Corina Machado a month after that country's marred presidential elections. Shutterstock

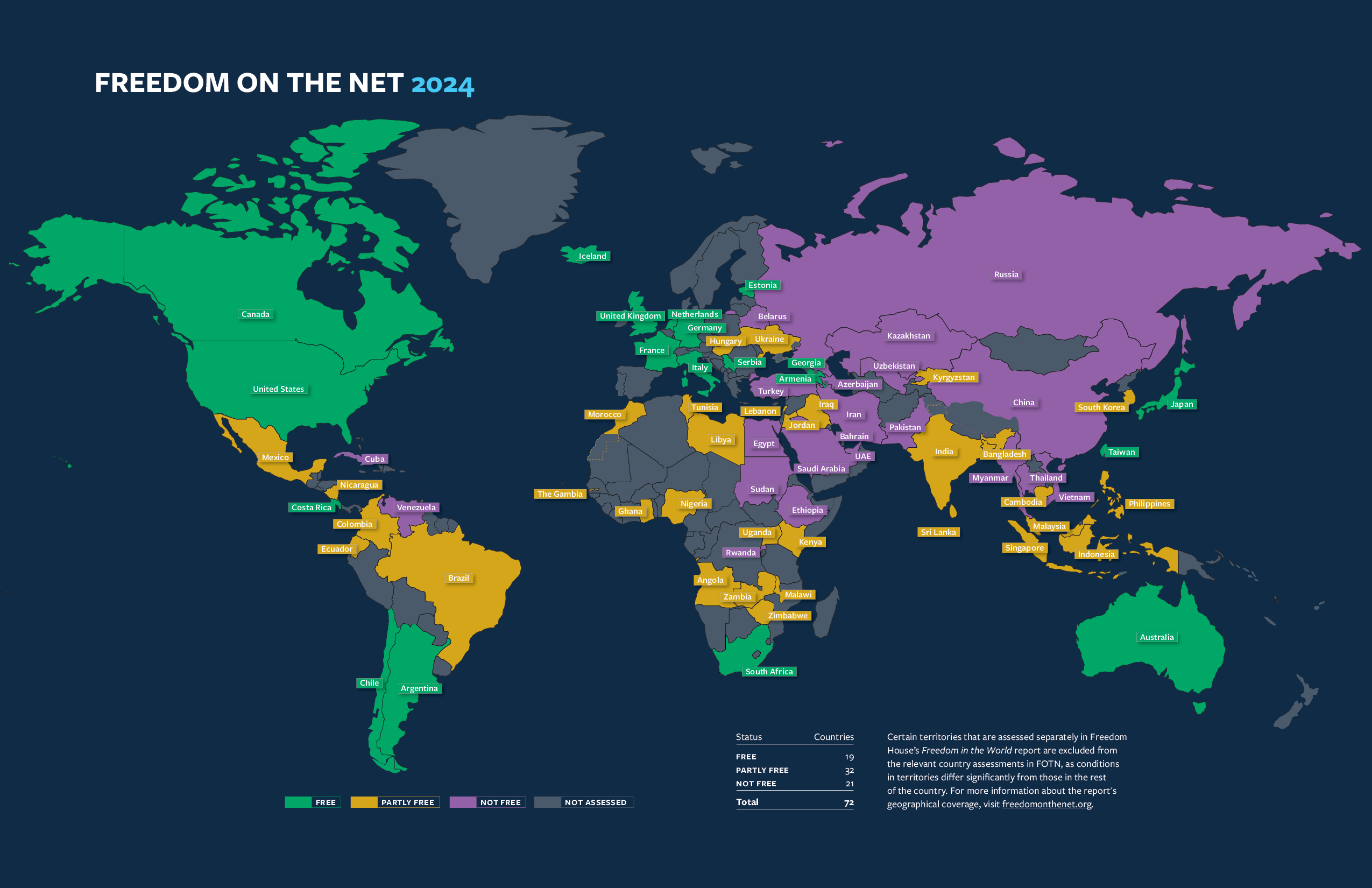

Every year, I pay close attention to the results of the Freedom on the Net report from Freedom House, the nonprofit organization founded in 1941 to advance democracy and human rights. The depth and global breadth of the annual reporting–the Freedom House team works with nearly 100 analysts and advisors to produce close analyses of more than 70 countries–makes these documents necessary reading for anyone concerned with issues at the intersection of technology, freedom, and democracy.

But the reality is that these reports make for grim reading. Consider just the past three years of headline results. In 2021 it was “The Global Drive to Control Big Tech.” In 2022, “The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule.” And in 2023, “Advances in Artificial Intelligence Are Amplifying a Crisis for Human Rights Online.”

Indeed, every year for 14 consecutive years, Freedom House has assessed that global internet freedom is on the decline. Every year, there are more reports of governments suppressing dissent, of people who were arrested for nonviolent expression, and of those who were attacked or killed for their online activities. Internet shutdowns, censorship, and the increasing sophistication of authoritarians deploying technologies such as artificial intelligence to manipulate and control populations are all phenomena metastasizing alongside the general decline in democracy and the rise of repressive regimes that Freedom House tracks in its Freedom in the World reports, which also appear annually.

So perhaps I should not be surprised to find that the headlines from this year’s installment of the Freedom on the Net report, released today, generally follow the same distressing trajectory as prior reports. But in this ‘year of elections’–it’s become trite to talk about the extraordinary number of elections around the globe in 2024–this year’s report also identifies a set of concerning phenomena related to this most fundamental act of democracy:

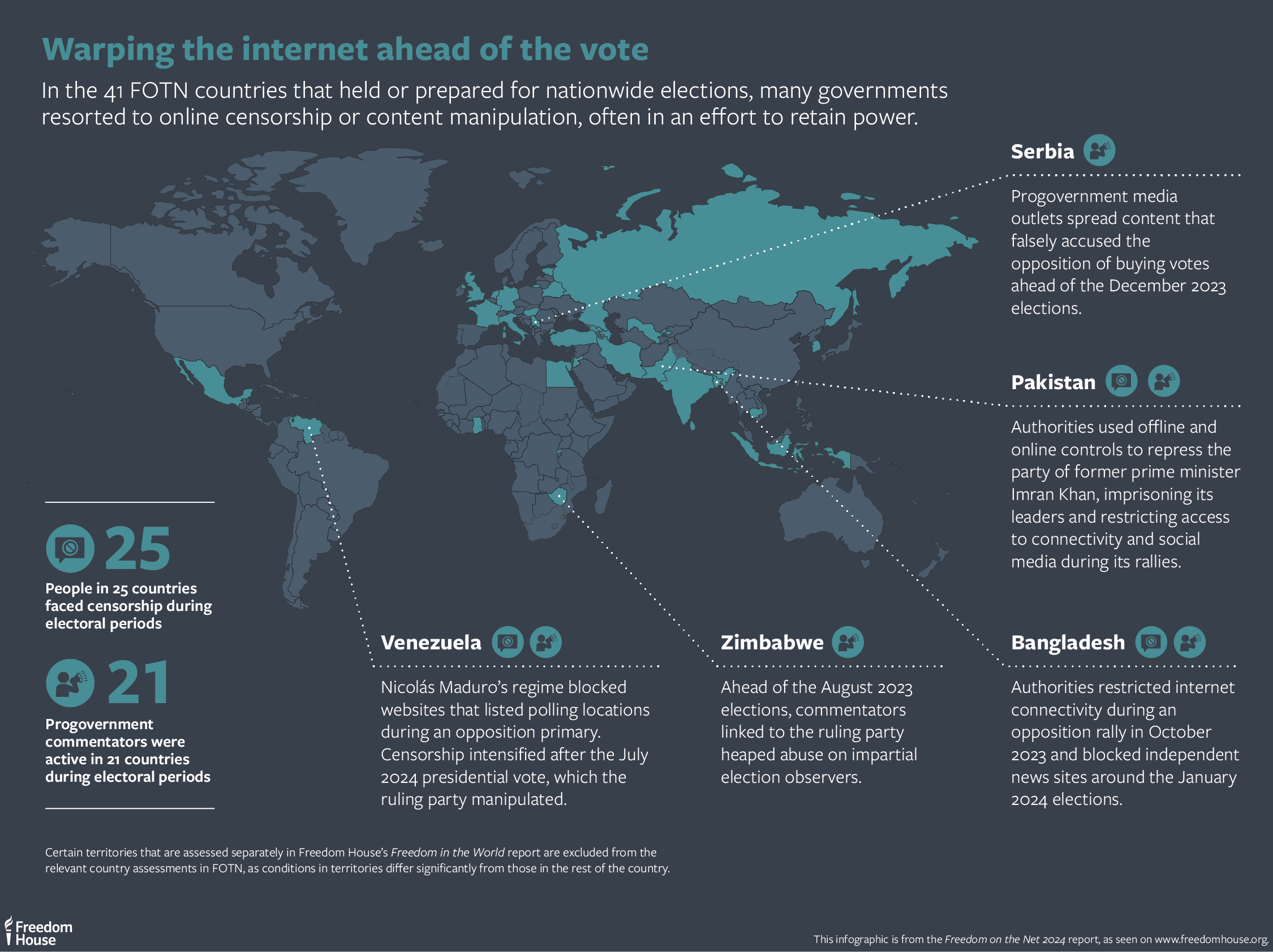

- “Censorship and content manipulation were combined to sway elections,” with voters in 25 of 41 covered countries that held elections during the reporting period contending with some form of censorship. In 21 of those countries, “progovernment commentators manipulated online information, often stoking doubt about the integrity of the forthcoming results and seeding long-term mistrust in democratic institutions.” Examples given include Cambodia, Bangladesh, Belarus, Pakistan, Venezuela, and more.

- Multiple governments “launched direct attacks–in the form of disinformation campaigns, online harassment, or other forms of political interference” on independent researchers and fact-checkers “dedicated to unmasking influence operations and boosting trustworthy information.” Examples given include Egypt, where that country’s media regulator “launched an investigation into the fact-checking platform Saheeh Masr.” In South Korea, the government “raided and blacklisted independent media outlets” and “launched a campaign to tar” the country’s “primary fact-checking platform, the nonprofit SNUFactCheck, as biased.” And here, the United States merits a mention: Rep. Jim Jordan’s (R-OH) House Judiciary Committee campaign against independent researchers is cataloged alongside the efforts of other authoritarians who would prefer to preserve their ability to traffic in falsehoods without facing scrutiny.

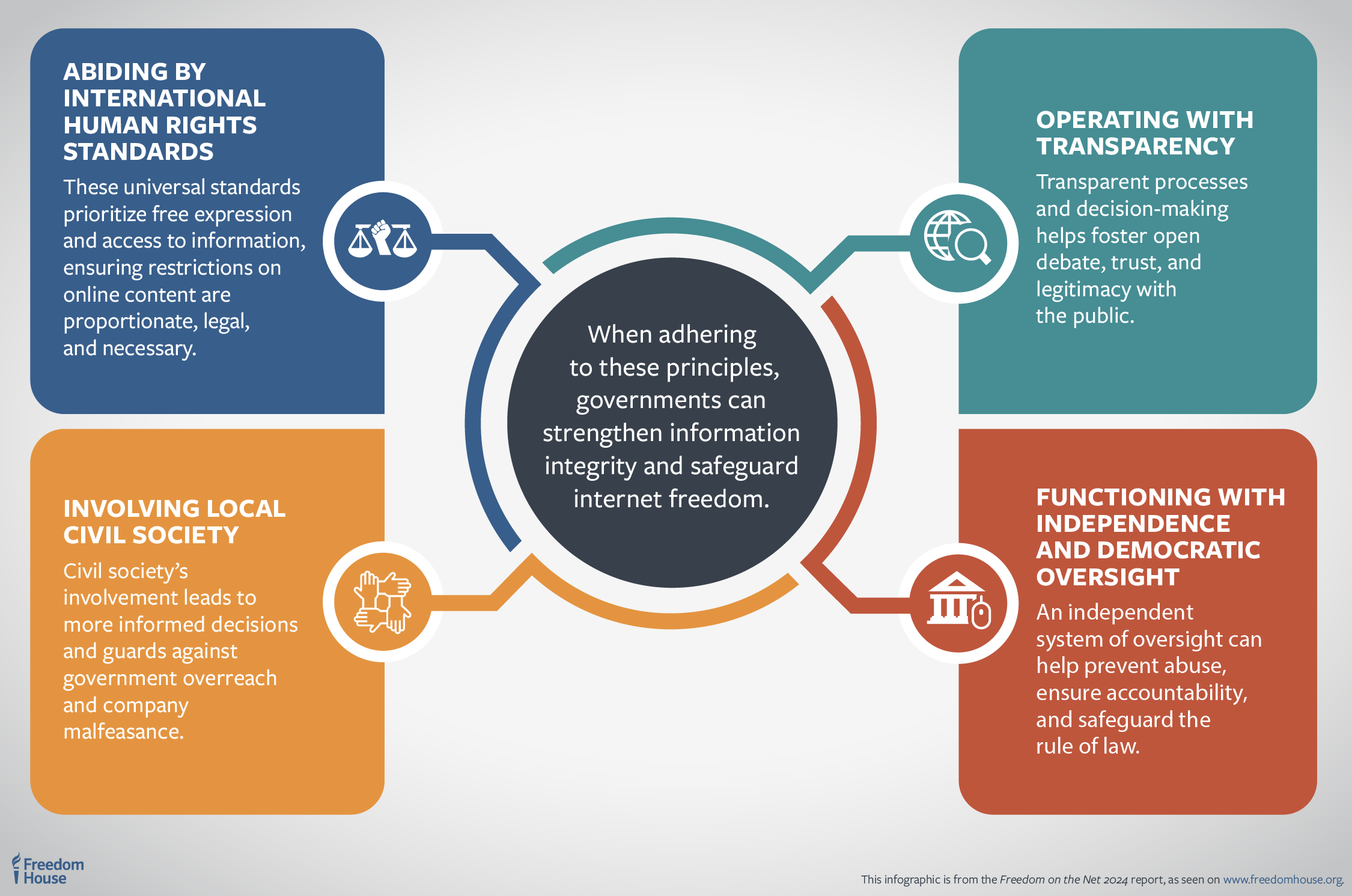

- While many nations “took steps aimed at addressing information integrity,” from “enforcing rules related to online content, supporting fact-checking and digital literacy initiatives, and passing new guidelines to limit the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in campaigning,” the report notes these efforts had a mixed effect on human rights and free expression online. There were, however, standouts: “South Africa, Taiwan, and the European Union served as the most promising models.”

The report focuses substantially on this point, trying to find a way to convey the appropriate calibration of efforts and actions taken by governments to preserve information integrity in order to avoid introducing negative consequences for free expression. Examples where things went awry are numerous. In Indonesia, the government “launched efforts to address purportedly illegal content online, but the initiative was marred by opacity that raised concerns about abuse.” In India, “partisan officials forced tech companies to toe a favorable line ahead of the 2024 elections,” and in Brazil, “millions” were temporarily “severed” from X after Elon Musk refused to abide by a judge’s orders.

A map of government efforts to manipulate the information environment ahead of elections prepared by Freedom House analysts.

But the positive examples are also worthy of note. South Africa’s “Real411” portal, a partnership between the country’s Electoral Commission, a civil society group, and citizens, surfaced false claims, incitement to violence, and other online harms for evaluation by “media, legal, and technology experts” to monitor for violations of law. Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA) earns a plaudit for its “regulatory toolkit” requiring transparency reports, risk assessments, and researcher access to platform data. Taiwan’s Cofacts fact-checking platform, as well as India’s Shakti Collective and the Mexican National Electoral Institute’s Certeza project, also received plaudits.

A graphic prepared by Freedom House analysts representing five key principles to strengthen information integrity and safeguard internet freedom.

Many of the recommendations in this year’s Freedom on the Net report are similar to years prior. Tech companies are called on to resist government interference and censorship, and to fully staff the teams responsible for working on election integrity. They are called on to support independent research, to mainstream end-to-end encryption, and to put up a fight when governments demand account details on “human rights defenders, civil society activists, journalists, or other at-risk individuals.”

One thing that comes into focus for me when reflecting on these reports is the reflexive nature of the various forces they document. Social media platforms, which do not invest enough in election and civic integrity efforts in the US, much less abroad, create plenty of reasons for governments to want to address the chaotic discourse they harbor, rotten as it is with mis- and disinformation, hate and harassment, incitement to violence, campaigns to delegitimize election outcomes, and various other problematic phenomena related to elections. Those interventions go better in some places than in others. But one constant is American technology firms, who give the authoritarians plenty of ready excuses through their inaction and inattentiveness to countries in markets they deem less valuable.

Map of internet freedom as assessed by Freedom House analysts. Freedom on the Net 2024

The report also brings into sharp focus the importance of “coordination among democracies” on internet freedom issues. The US has always played a leading role in such coordination, but its renewed commitment may be tested depending on the outcome of November’s elections, particularly given former President Donald Trump’s dismal record on the matter.

Whether next year’s installment of Freedom on the Net will bring a change in the overall trend will require a lot of things to go right all at once. For now, we can take some comfort in singular bright spots in this 14th edition–like Chile and the Netherlands, both assessed as global models for internet freedom in their first year under consideration. But even if they are uncomfortable, the findings in these reports are valuable for anyone working to improve things. At the very least, we know we haven’t yet hit rock bottom.

Authors