Dissent and Resistance to Silicon Valley AI Narratives

Scott Timcke, Hanani Hlomani, Mark Gaffley, Liz Orembo, Theresa Schültken / Mar 21, 2023Hanani Hlomani, Mark Gaffley, Liz Orembo, Theresa Schültken and Scott Timcke are researchers affiliated with Research ICT Africa, a nonprofit think tank located in Cape Town that is committed to digital equality and data justice in Africa.

“Feminism is a political project about what could be. It’s always looking forward, invested in futures we can’t quite grasp yet.”

-Lola Olufemi

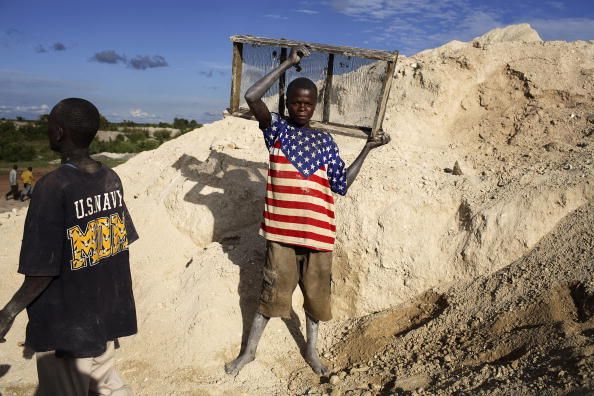

Biassed AI decision-making does shape who receives credit to purchase a house. AI content moderation does lead to the spread of hate speech and misogyny. The devices we hold are produced on the back of exploited African miners, many of which are children, and assembled by low-paid workers in smartphone sweatshops in developing countries. These commonplace consequences are both devastating and typically hidden from everyday view in the Global North. Sometimes, a willful ignorance drives a disengagement from knowing about the systematic processes that create these harms. But these outcomes are not inevitable.

Building the futures that writer, organizer and researcher Lola Olufemi points to requires critical feminist AI research. We understand this project as explaining the causes which allow harm and subordination to be reproduced. Pairing feminist resistance with the concepts of slow violence and legalized lawlessness can highlight where evidence of dissent and resistance can be found in AI research. But we should not stop here. There is a need for AI research that uncovers current ways of resistance across the entire AI lifecycle “from birth to death,” to use Kate Crawford’s turn of phrase.

Setting the scene

Silicon Valley marketers promise that consumer AI products will improve lives, reduce poverty and promote economic inclusion. Some developing countries lean into this rhetoric, as these promises speak to their aspirations. South Africa is a good example where celebrant discussions about the 4th industrial revolution are ubiquitous and have been adopted as a key pillar of the national economic strategy.

As African feminists have argued, these promises are illusory at best. Typically, these new technologies disproportionately serve those who are already wealthy, providing them with more clout. For example, global monopolies have consolidated their financial might by extending their infrastructure to collect data and expand into every market in all the regions. The result is widened inequalities, human rights violations, and even shrinking democracies.

Going beyond immediate effects to make data extraction visible

African feminist scholars have emphasized how extractivism is an important mechanism of algorithmic capitalism. Extractivism is defined as “as the accumulation of wealth through the extraction of a broad range of natural and human resources [...] and the exportation of this wealth to the centres of global capital.” The historically shaped global hierarchy of colonialism must be taken into account, whereas African countries were and still remain the suppliers of raw materials and labor. On the AI lifecycle Crawford writes about, we believe the first phase is about the necessary conditions to bring AI to life in the form of mining the rare earths like cobalt and lithium for the production and subsequent assembly of the hardware. We call this the prerequisite stage.

Using the lens of extractivism can generate awareness as to which actors are involved in the processes, and that it is in itself a source of (masculinist) power shaping society. Feminists have argued that the extraction of natural resources is strongly connected to a masculinist view of living, where more and more resource consumption is needed. This is justified by a masculinist view that it is one’s right to have access to all bodies. Moreover, it refocuses research towards the impact extractivism can have on local communities and analyzes it using an intersectional lens on race, class and gender.

The impact of extractivism can be visible, but it can also take the form of slow violence– that is, a form of violence that is difficult to see or measure. This second kind of extractivism can go unnoticed because it lacks the dramatic spectacle of more sudden and visible forms of ecological collapse. Being systemic and gradual, slow violence can have far-reaching and long-lasting impacts on communities and the environment, and it often stems from systemic inequalities and power imbalances.

Rob Nixon explains one kind of slow violence as environmental degradation: exposure to toxic chemicals, pollutants, and other forms of environmental degradation that can have long-term impacts on people’s health and the environment. For example, studies have shown that communities living near toxic waste sites have higher rates of cancer, respiratory illnesses, and other health problems. This is important to consider in the context of new consumer technologies because critical resources like rare earth minerals are needed for the production of necessary hardware components.

It is not enough to limit our view to the extraction of natural resources. Indeed, if we look at the second phase of the AI lifecycle, we can identify the extraction of data to train AI and develop models and the emergence of the human cloud as further problematic areas. The term “human cloud” is used to refer to the growing arrangement of digital marketplaces for labor where workers engage in the ‘race to the bottom’ by counter bidding for work. Similar to feminists’ calls for the recognition of womens’ invisible and unpaid labor, we call for the recognition of these extractions happening for AI development.

While automation and the whole AI industry boldly promises improvement of work and service delivery by replacing humans with machines, ‘replacing humans’ through automation reduces their work into a digital architecture that is visible to the managers and owners of infrastructure to shrink human labor and reduce production cost. With this, capitalists have realized how to transform human labor into the gig economy and open it to populations with lower bargaining power. While one may argue that this creates an opportunity for women to work from home and be involved in the digital economy, it only expands the problem of unpaid labor as women have to extend their working hours.

Our argument can even be stretched further: A third form of digitally-enabled slow violence is the employment of such tools for governing the impoverished. In the US, programs have historically subjected vulnerable people to high levels of surveillance in ways that reproduce their marginalization, as Virginia Eubanks explains. Rather than a break with the past, the use of AI to govern inequality is a continuation of longstanding bureaucratic, statistical, and algorithmic processes used to surveil people in conditions of poverty. These consequences need to be considered in the last phase of the AI lifecycle, namely the impact stage, accounting for the strong effect of surveillance, classification and experimentation on societies.

Questioning justifications

Historian Caroline Elkins has spent her career identifying how the British Imperial elite convinced themselves that abuses of power were always justifiable in the end. Elkin’s concept of legalized lawlessness captures imperial violence perpetrated against colonial subjects. Coercion and reform rested with each other, and religion and free trade were violently introduced as a way of transforming ‘backward’ societies. The British empire would insist on the rule of law, while also conducting atrocities where investigations were whitewashed, or laws passed and backdated to legitimize lawlessness.

The Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya is a good example of how the British justified torture through the rule of law. Elkins’ work reveals how liberation movements across the British empire confronted circumstances where anything they did was deemed illegal, whereas anything the rulers did was deemed justifiable. When power is threatened, new law is promulgated to sanctify oppression.

As the free flow of information is critical for democracy, authoritarian inclined African state actors seek to control narratives through blocking online platforms. Law enforcement agencies find new loopholes within the law to harass dissent and in other instances, government agencies develop laws that enable blanket criminalization of disinformation, but which is a pretense for stalling the growth of popular resistance movements.

On the subject of new forms of law, amid the growing global concerns on information disorders, privately-owned social media platforms argue that they are best left to self regulate using AI ethics. As much as these platforms aim to moderate content in the interest of the public, where these interests clash with the interest to generate profits, company interests always seem to prevail. And where it does not make economic sense - like countries in the Global South with small markets - there is little interest to invest and contextualize approaches to content moderation. What remains is a self-serving AI guided distribution of content, without responsible actions to respond to violence in the face of growing appetites of authoritarian governments to regulate content.

Uncovering resistance

In his book Domination and the Arts of Resistance, James Scott explains hidden transcripts as forms of dissent and resistance which are kept out of sight from those in power. Starting from the observation that “it seemed like the poor sang one tune when they were in the presence of the rich and another tune when they were among the poor”, Scott argued that in oppressive systems, hidden transcripts are used as a weapon for the oppressed to safeguard their security. Hidden transcripts are used in spaces where the subordinates gather outside the presence of power, and where discussion can develop counter narratives that oppose public conformity with official narratives. The subordinates learn the language of the powerful and default into their native language in hidden transcripts as a symbol of solidarity.

At the core of the concept of hidden transcripts is how people navigate asymmetric relations of power, visibility, and traceability, items that are also central to data infrastructures. For example, machine learning algorithms reproduce existing inequalities found in their training data. Some of these underlying social inequalities are the result of differences in visibility where some people are more likely to be targeted or excluded from data collection. Furthermore, surveillance systems make targets more visible or legible, while the surveillance itself remains relatively opaque.

Hidden transcripts appear in Internet policy research. Many narratives are shaped by the Global North, with systems of donors using monitoring and evaluation exercises to track reporting done by organizations in the Global South. As Africans are constricted to neo-colonial and aid ties, they are unable to fully articulate their own solutions or form their own narratives in Internet governance. Being aware of hidden transcripts is fundamental to understanding reactions and resistance to AI. Combining the concept with feminist methods, this kind of research is crucial for shaping the future of AI.

Shaping the future

African feminist perspectives offer many resources to enrich our understanding of the impact of and resistance to AI. The concept of slow violence can guide research into how these impacts unfold and the concept of legalized lawlessness exhibits the justification of current practices. Together they provide researchers with the tools to trace extractivism in the digital age. Similarly, the concept of feminist hidden resistance is important to acknowledge various forms of opposition to current practices and public understandings of AI.

All of these concepts need to be understood by using a holistic assessment of the AI lifecycle that encompasses the precondition stage, the development stage and the impact stage of AI as described above. This approach helps researchers to assess the broad causes and consequences relating to AI.

To make it more concrete, AI research needs to shift focus. Currently researchers and policymakers in the Global South tend to prioritize immediate and visible developments while unduly neglecting the slower and relatively less visible processes that are also reshaping politics, societies, and markets. Equally, considering these slower forces can help AI policy researchers broaden their point of view while prompting them to address long-term transformations.

It is helpful to understand how current forms of extractivism and oppression are justified by using methods of legalized lawlessness. Moreover, there is value in being explicit about how narratives about technology are shaped in the Global North, leaving little space for people in the majority world to shape their own perceptions of technology. All of this is needed to continue to build on the feminist project “about what could be,” as Olufemi reminds us.

*Authors listed alphabetically by surname. As contributions were equal, first authorship is interchangeable.

Authors