Dissecting Big Tech’s Shareholder Showdown

Jan Rydzak / Jun 16, 2022Jan Rydzak is the Company and Investor Engagement Manager at Ranking Digital Rights.

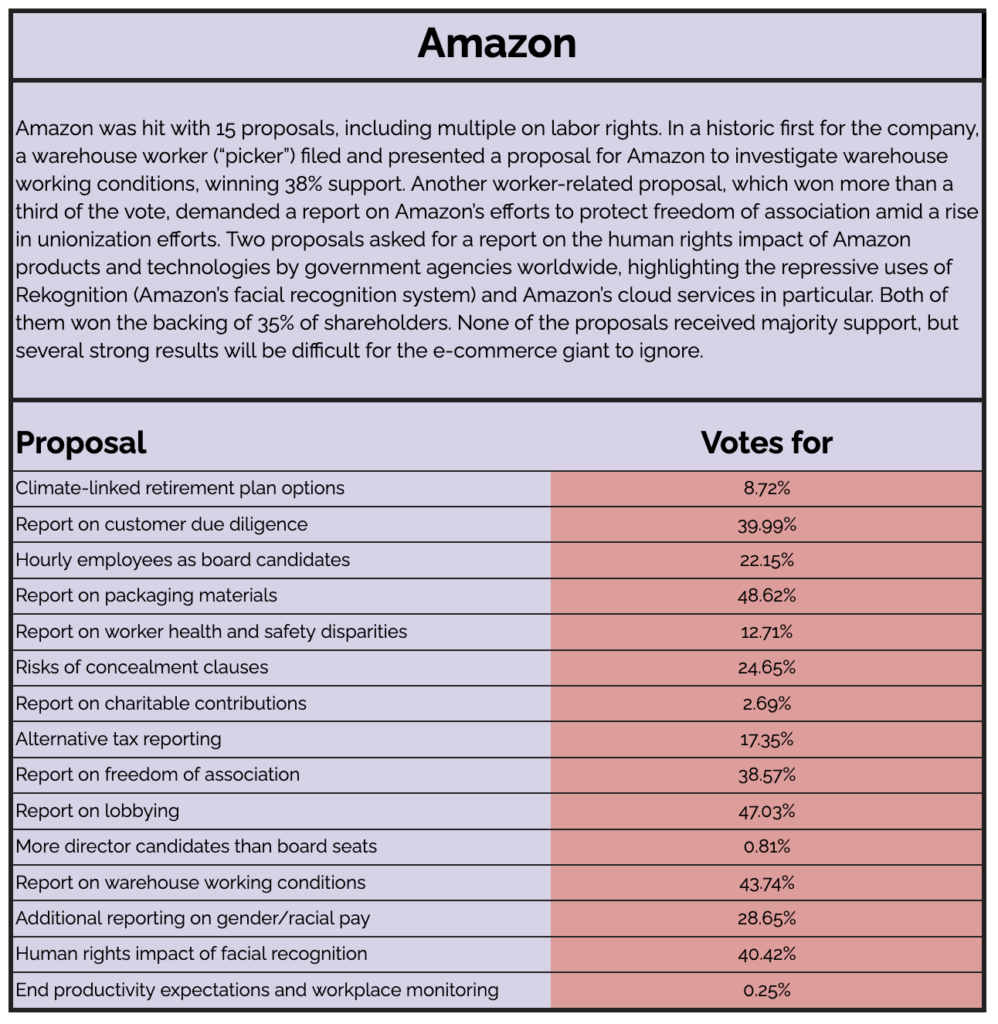

Over the past weeks, Amazon, Meta, Twitter, and Alphabet (Google) all faced a shareholder reckoning. Nearly 50 petitions launched by investors across the four tech giants called on them to come clean on an array of issues. Many of those issues were related to human rights. The topics on the table: surveillance products and their use by government agencies, the corrosive impact of targeted ads, ensuring the safety of warehouse workers, and more. Shareholders voted on all of them.

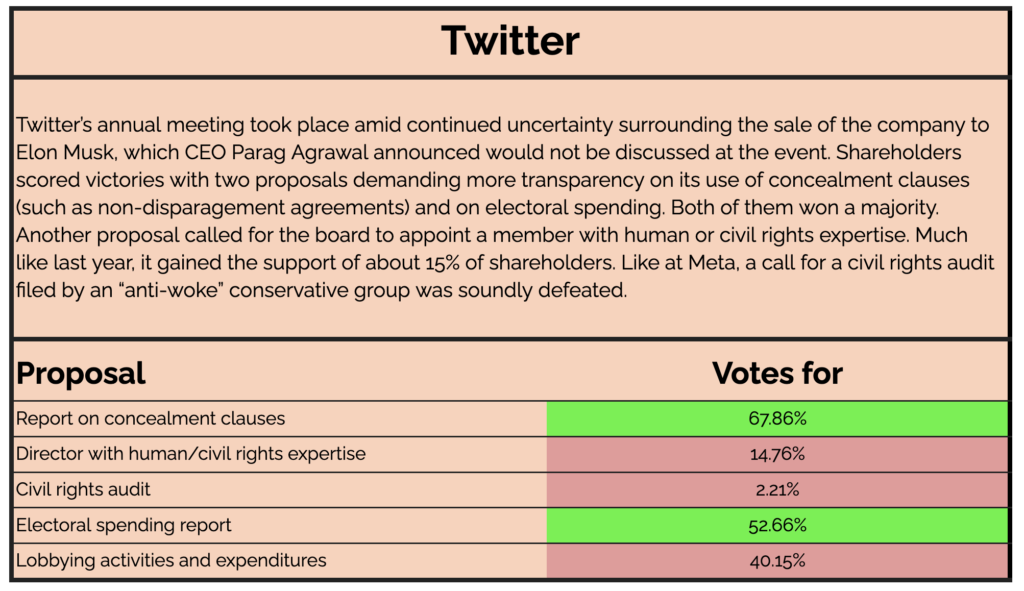

On the surface, the outcome was disheartening: only two proposals won a majority of shareholder votes, both of them at Twitter. But the raw numbers obscure a much more complex picture.

This year’s wave of investor action on human rights has proven stronger than any in the past. The volume and range of proposals has reached record levels, breaking into issues that the investor community formerly hadn’t explored. A critical mass of shareholders has backed human rights motions, even when it was clear that the artificially outsized voting power of Google and Meta’s corporate leadership would nullify their chances of winning a majority, thanks to the companies’ multi-class stock structures.

There are good reasons to expect that investor-led pressure for corporate accountability will continue to flourish. Let’s dive into them.

Shareholder Meetings 101

Shareholder proposals are one of the most powerful tools in the activist investor’s toolbox. They democratize the mechanisms that govern a company’s operations by putting issues raised by investors to a vote. Civil society organizations often support proponents in crafting and amplifying their demands.

The voting process works both as a referendum on the company’s leadership and as a barometer of shareholders’ sentiment about how the company is navigating key issues. Proposals are advisory, but strong support creates a powerful incentive for boards to take action or face further backlash. Losing shareholders’ trust is ultimately a prelude to losing their capital.

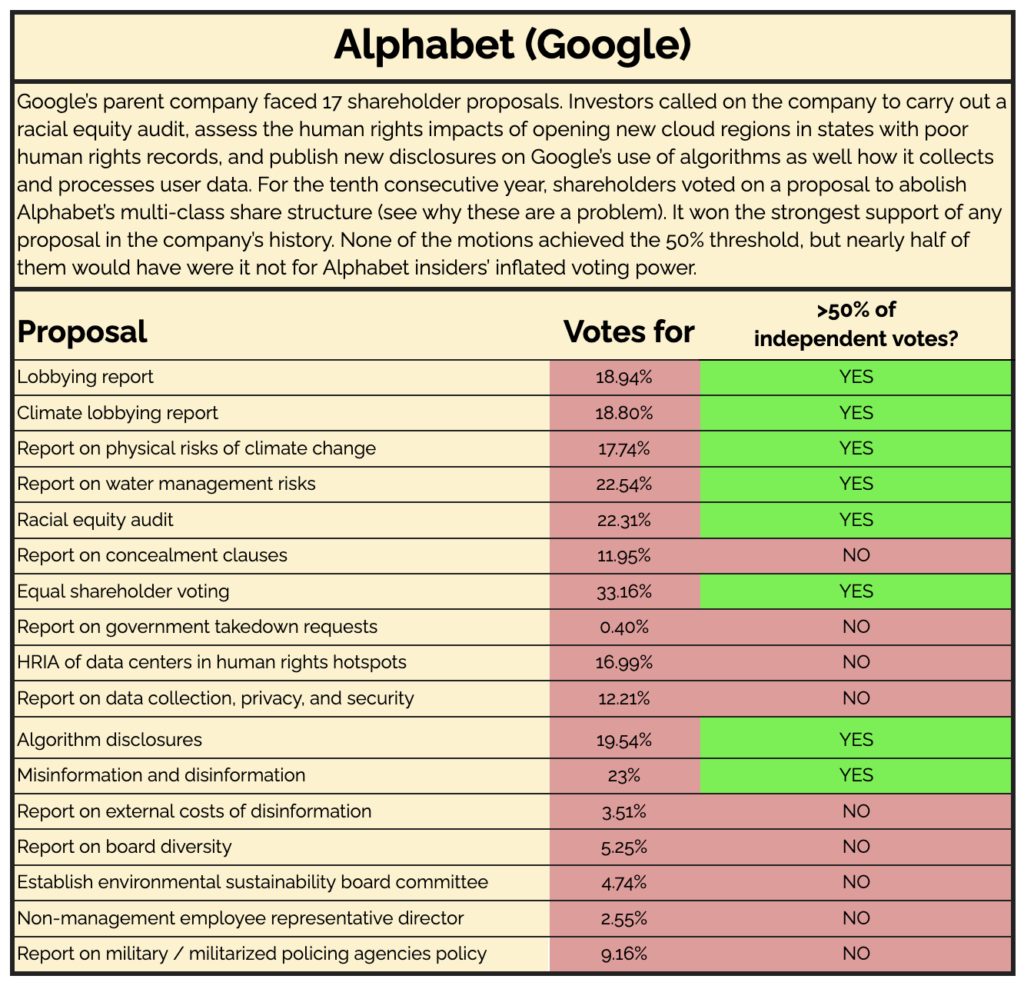

Echoing the ongoing boom in ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing, shareholders this year have hit many tech companies with more proposals than they had ever received. The 17 proposals at Google, 15 at Amazon, 12 at Meta, and five at Twitter all set an all-time company record. Support for those that tackle social and environmental issues has grown rapidly, often hitting more than 30%—a threshold commonly viewed as critical to compel executives to take action.

Most proposals fail to earn an absolute majority, but dragging an uncomfortable issue into the spotlight and keeping it there is a big deal in itself. As recent history shows, sustained pressure pays off. Two years ago, Apple bent to relentless public appeals by both investors and civil society when it published its first human rights policy. Last year, Microsoft promised an independent human rights assessment of its surveillance and law enforcement contracts, in part as a compromise to activist investors. Similar examples abound.

A Cascade of Wake-up Calls

Seasoned investors have made it clear this year that they are no strangers to the nuances of the human rights issues that affect their holdings. Algorithms, ad targeting, unbridled data collection, and deals involving government actors with a penchant for repression were all up for a vote at tech companies this year.

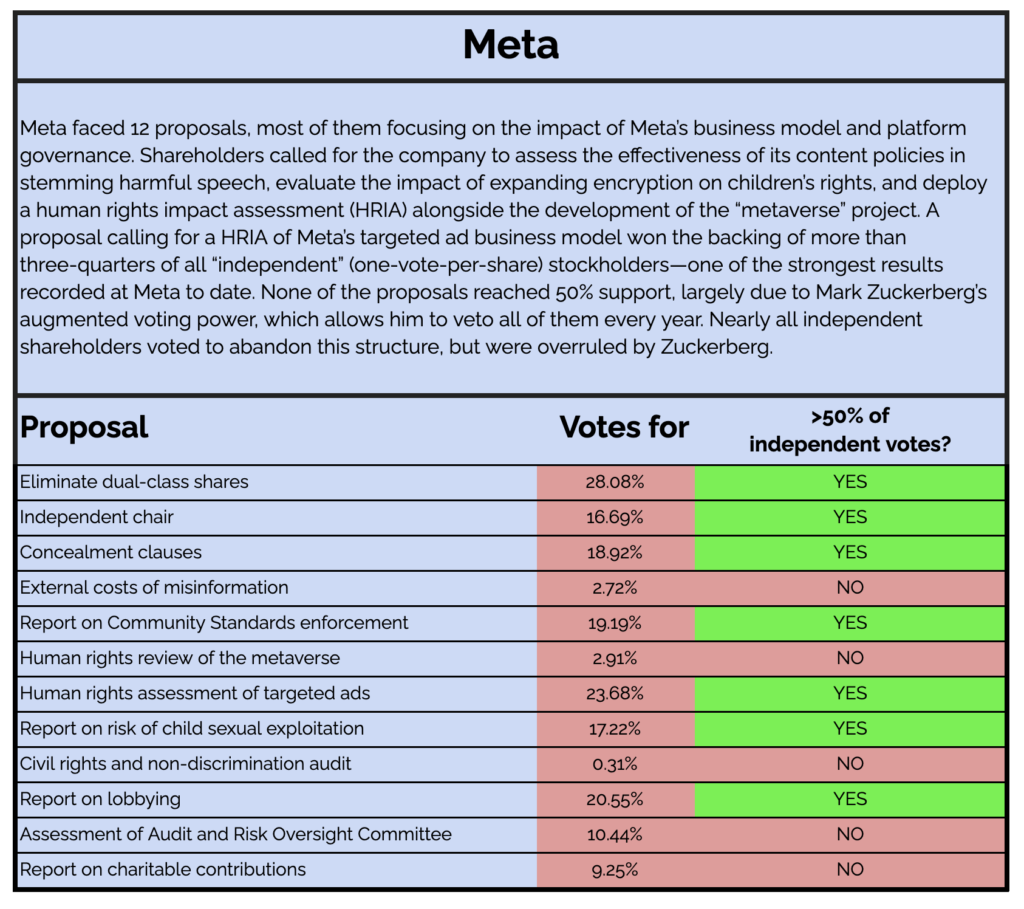

At Meta, excluding Mark Zuckerberg’s votes, about 80% of shareholders voted for a human rights impact assessment (HRIA) of the company’s ad targeting system. The proposal, which the organization I work for directly supported, underscored that Meta has never revealed any data on the ads it restricts and never offered more than a cursory remark on the topic in any of its previous HRIAs.

The proposal ultimately secured the second highest number of votes of the 12 that were on the table this year—one of the strongest shows of support for a shareholder proposal in the company’s history.

Why does this matter? Because it signals that, in the eyes of investors, the balance between maximizing profits and protecting users’ rights is shifting in favor of the latter. Increasingly, shareholders are not just asking for a reckoning with the impact of specific business decisions, but with the entire architecture of Big Tech. As the proposal’s authors put it, Meta is “nibbling around the edges of a problem instead of looking at the root cause–the overarching systems that govern targeted ads.” In other words, it’s the business model.

Companies’ expansion into new digital and physical spaces also came under fire. Shareholders challenged Meta’s vision of the future, calling for a human rights review of its plans for the “metaverse.” A week later, Google’s investors slammed its plan to open cloud regions in human rights hotspots like Saudi Arabia. The company has shown no evidence of the due diligence it conducted in light of the country’s appalling human rights record, which includes brutalizing activists and operating extensive digital surveillance networks.

Neither proposal came close to reaching the 50% support threshold—an unachievable feat, thanks to the company’s multi-class stock structure. But the message was clear: wherever major business decisions have shown their capacity to cause harm, there will be an investor rallying allies to push for accountability.

No Escaping Civil Rights Accountability

Three of the shareholder meetings took place on the anniversary of George Floyd’s murder. All of them took place in the wake of the racist massacre at a Buffalo supermarket, which the perpetrator livestreamed on the Amazon-owned Twitch. The mass murder was yet another horrendous touchpoint in a history of systemic violence that technology has often aggravated.

Corporate boards are facing a surge of investor-led rebukes on their lackluster civil rights efforts. Demand for change has skyrocketed since 2020, when Facebook released a damning third-party assessment dissecting how the company’s failure to rein in noxious posts and ads resulted in “significant setbacks for civil rights.”

Calls for comprehensive civil rights audits have swept through tech companies, mirroring broader trends. Earlier this year, a group of shareholders celebrated a victorious proposal at Apple demanding a third-party assessment of the company’s impact on civil rights. Amazon announced an audit of its own in April, conceding to a campaign by a group of New York pensions funds that had gained strong momentum.

Shareholders also rallied around a call for a racial equity audit at Google, clinching the fourth strongest result of all the proposals the company faced this year. This petition too grew out of investors’ apprehensions regarding Google’s business model, which has made it the most dominant advertising force on the internet. Journalists had previously revealed that Google’s targeting platform gave white supremacist content a pass while blocking terms related to social and racial justice.

Every Share Gets One Vote (Except When It Doesn’t)

Unprecedented shareholder pressure has moved companies to try to insulate themselves from it. Case in point: last year, a record 56 tech companies—nearly half of all tech IPOs—went public with structures that granted founders and insiders inflated voting power over ordinary shareholders.

Now endemic in the tech sector, stock structures with two or more classes (known as dual- or multi-class stock) exist under the premise that “visionary” founders and their allies should have free rein to maximize growth and innovation. In most cases, this gives a small superclass of corporate elites 10 or more times the voting power of regular investors, who generally get one vote per share. This means they can minimize their personal investment in their own company while maximizing their clout. At Snap, shareholders receive no voting rights at all—a deeply undemocratic formula for perpetual corporate power.

When they debuted on the stock market, Meta and Alphabet both baked these structures into their business models. Officially, of the 155 proposals the two companies have jointly received since they went public, shareholders have never approved a single one. In reality, seven out of the 12 proposals shareholders voted on at Meta this year would have won a majority had Mark Zuckerberg not personally blocked them with a single vote. (Amazon and Twitter give each share one vote.)

On May 25, a record 92% of shareholders who were not Zuckerberg voted to terminate Meta’s warped voting structure. At Google, which has a separate class with no voting power, the same proposal won more support this year than any other in the company’s history. Yet in both cases, the very existence of multi-class structures guaranteed the proposals would never secure a majority.

Investors, activists, and academics oppose multi-class share structures almost unanimously. The normative arguments are clear. Outsized voting rights transform an ostensibly democratic process into one that is rigged by design. They entrench unaccountable management while disenfranchising ordinary shareholders. They offload the risks of irresponsible decisions on shareholders. Because retirement funds are almost certain to include a who’s who of tech companies, the public ultimately pays the price.

But distorted power structures are not inevitable. In the US, the SEC and Congress both have avenues to curb the use of dual-class shares or ban them entirely. And to keep corporate power from spinning out of control, that’s exactly what they should do. In pursuit of this goal, a coalition of human rights organizations led by Ranking Digital Rights has recently sent a letter to the SEC demanding that it put an end to multi-class shares and other structural barriers to shareholder action on human rights.

The Spark is Lit

A casual observer might look at the success rate of this year’s shareholder proposals and see a string of campaigns that the corporate boards of American tech giants have successfully deflected.

But investors’ willingness to take action on human rights is on the upswing. So is their appetite for partnering with civil society. The groundswell of support for collective human rights statements by investors with trillions of dollars in assets reflects this well.

Shareholder advocacy is no longer an elite domain. Investors and human rights advocates can and must mutually reinforce the specialized power they each possess to trigger good change. If we want Big Tech companies to use their enormous power to support human rights and democracy, or even avoid undermining them, we have to cultivate more open exchanges between these two groups. It’s one of the most promising paths forward.

Authors