Digital Disruption: Measuring the Social and Economic Costs of Internet Shutdowns & Throttling of Access to Twitter

Theodora Skeadas, Rehan Mirza, Maya Vishwanath / Sep 25, 2023Rehan Mirza is a a researcher at the Shorenstein Center at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Maya Vishwanath is a researcher and consultant and a graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Public Policy Program. Theodora Skeadas is a trust and safety professional and former Twitter employee.

Social media platforms today transcend the social. Beyond the traditional use case of connecting and communicating with friends and family, these platforms have evolved to be a source of news and education, a tool to disseminate ideas, and a method of marketing for individuals and businesses. Much attention was placed on their use as a coordination tool for social movements and uprising in the Arab Spring’s aftermath, dubbed by some as “a Twitter Revolution”.

But this potential for social coordination has been viewed with trepidation by authoritarian governments. With global internet freedom on the decline for 12 consecutive years (every year since the Arab Spring), restricting access to social media platforms or the internet more broadly is now a standard instrument in the repertoire of repressive tactics deployed by these governments to quash dissent.

These tactics cut across online and physical spaces, with website and platform blocks, internet shutdowns and cracking down on VPNs and other circumvention tactics accompanying promotion of state media, arrests, and threats of physical intimidation. In a recent instance, mobile internet in Senegal was shut down across the country from July 31 to August 2 of 2023 following the dissolution of an opposition party and arrest of its president and leader by the incumbent government.

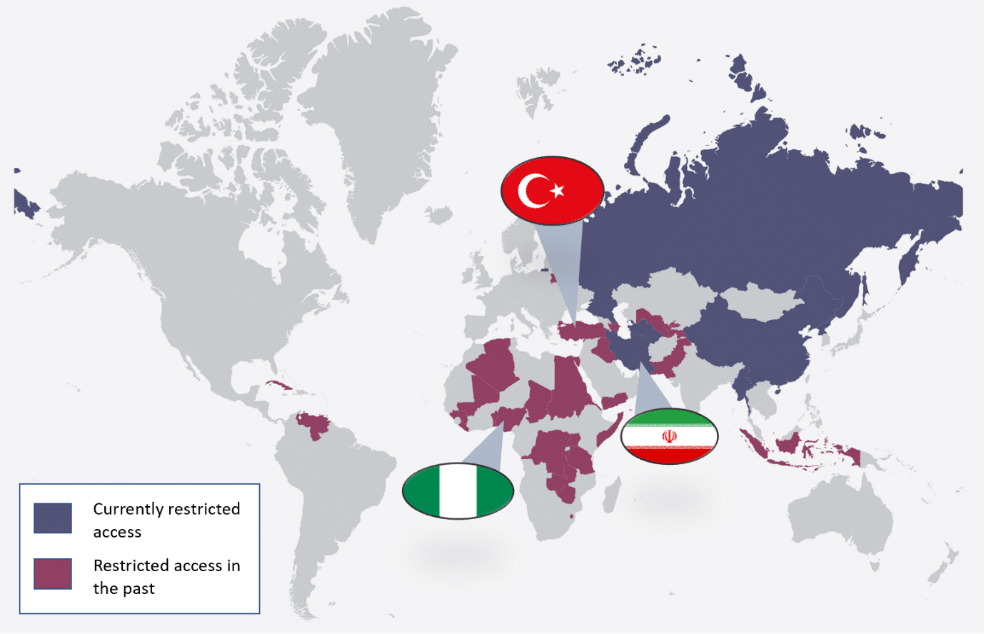

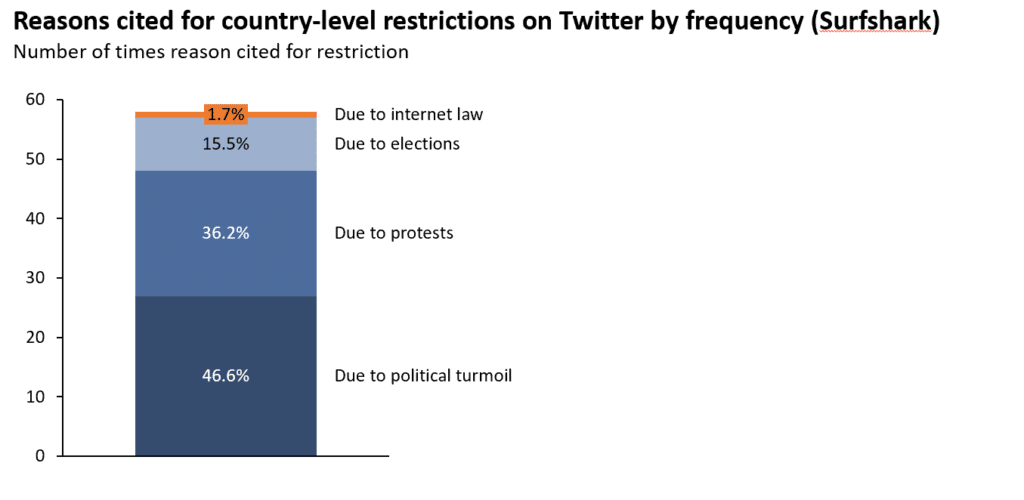

Our study focuses on how restricting access to Twitter (now X) may have had significant economic and social impacts across countries. As of April 2023, access to Twitter was restricted in 36 countries, affecting 3.2bn people worldwide. Political instability, protests and elections are key reasons for these restrictions. Through the lens of three case studies – Turkey, Iran, and Nigeria – we demonstrate the platform’s use for critical applications including global disaster and crisis response, social activism, and small and medium-sized business (SMB) activities, in addition to the platform’s use by the same government authorities who are restricting its use. Based on these use cases, we conclude that blocking or throttling access to the platform, and the internet more broadly, comes at considerable social and economic cost.

Turkey

Scope of digital repression

Restrictions on access to online content, including website shutdowns, temporary blocks to specific services, wholesale internet shutdowns, and imposed content regulation on services are instruments that the Turkish government employs as part of a broader policy to censor press and social commentary that is critical of the regime. According to Twitter’s 2021 transparency report on Removal Requests, Turkey was Twitter’s fourth largest requestor for legal demands, accounting for 9% of Twitter’s legal demands globally. That said, the last decade has seen Turkey moving away from the use of broad internet shutdowns, instead relying on censorship and content removal.

Geopolitically, Turkey is “vying for a position to be working with Europe and the EU, and is putting on a face of being relatively more liberal and open than some of its counterparts” (Digital Rights NGO #1)

The Turkish government uses internet restrictions and targeted shutdowns as an information control mechanism and to quell government criticism, particularly during times of social unrest. For instance, the frequency of internet controls increased from 2015-2017 in response to the Kurd resistance.

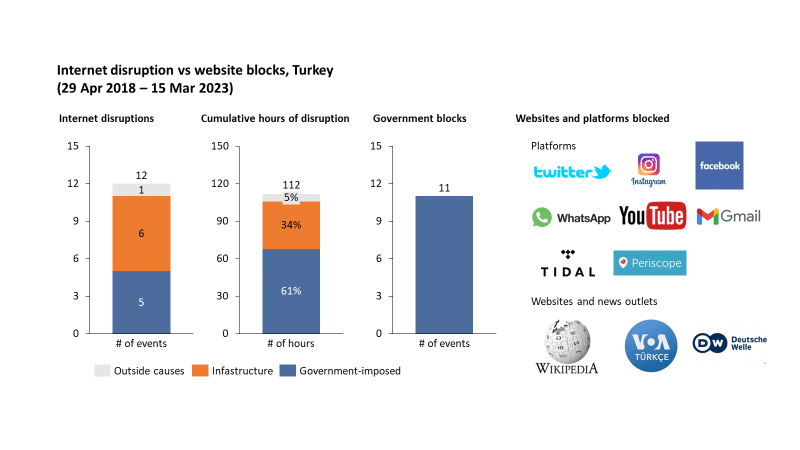

As Figure 3 shows, since April 2018, there have been 12 reported incidences of internet disruption in Turkey, resulting in 112 cumulative hours of disruption, and 11 incidences of government-imposed website or platform blocks. Government-imposed restrictions are responsible for 66% of total disruptions. Damage to infrastructure is the second leading cause of disruption to connectivity in recent years. Natural disasters, including forest fires in August 2021, and most recently the February 2023 earthquakes, have contributed to service outages. While some of these outages are in fact related to infrastructure damage, in other instances, the outages resulted from a “central decision by the government to make sure that citizens could not get online and spread information about the fires,” according to one digital rights NGO we interviewed. During this event, the slow and inadequate disaster response was an intentional step by the government to save costs, which sparked intense criticism online. During the February 2023 earthquakes, Twitter was blocked for 10 hours on 8th February.

Twitter as a Crisis Response Tool During the February 6th Earthquakes

At 4.17 am on 6 February 2023, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit Southern Turkey, followed by another Earthquake of magnitude 7.5 at 1.24 pm. The earthquakes were the most severe in the country since 1939, and required a large, coordinated rescue operation spread across 10 of Turkey’s 81 provinces. During this crisis, Twitter was an important communication tool, raising awareness about missing relatives and friends and the effects of the earthquake more broadly, coordinating search and rescue and aid delivery, and allowing those in danger to identify themselves and seek assistance.

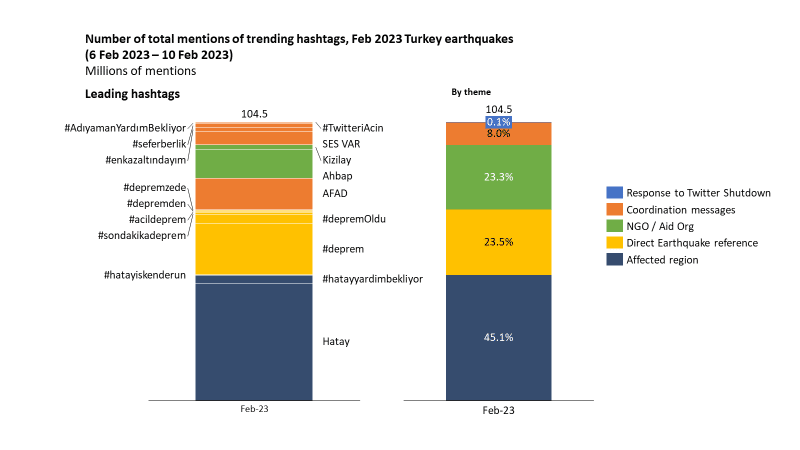

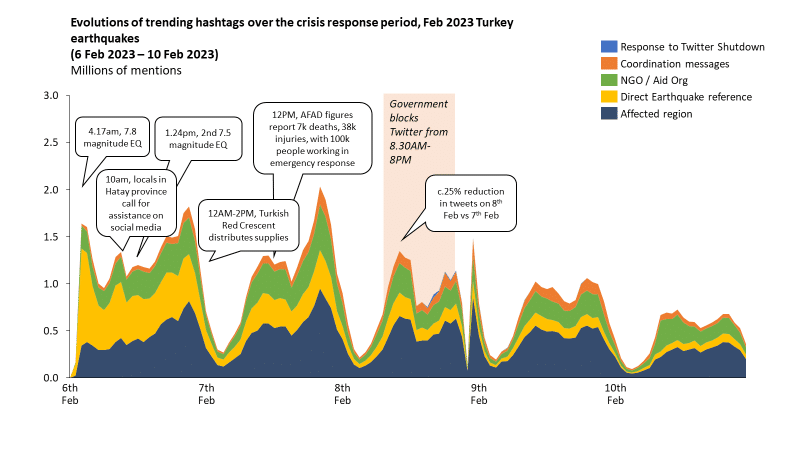

Figure 4 below presents a sample of the most prominent relevant hashtags used on the platform in the days following the earthquake, which total cumulative 104.5m mentions, signaling the scale of the response. The main themes of these hashtags were as follows:

- To draw attention to Hatay, the region at the earthquake’s epicenter

- References to the earthquake itself

- References to NGOs or aid organizations

Figure 5 below, which provides a timeline of this activity, highlights that the highest volume of mentions was on 6 Feb and 7 Feb in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, and a reduction in activity following a 12-hour government-imposed block on Twitter on 8 Feb. According to NetBlocks reports, the temporary block was due to government concerns about misinformation being spread on the platform. Regardless of the motivation for the block, it hampered the benefits of the tool in crisis response.

Nigeria

Scope of digital repression

While the Nigerian government has employed internet shutdowns as a means of information control in the last decade, it has primarily relied on more targeted social media blocks and restrictions in recent years.

“Rather than entire internet blackouts, censorship in Nigeria is leveraged on specific flashpoints only.” (Digital Rights NGO #3)

In 2021 and 2022, social media shutdowns in Nigeria summed up to 5,327 hours of disruption in total, impacting over 100 million users. The major event driving these numbers was the Nigerian government’s 222-day ban of Twitter which was in place from June 5th, 2021 to January 13th, 2022.

Nigeria’s Ban on Twitter

In June of 2021, Twitter deleted a tweet posted by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buharithat threatened retaliation against secessionist groups in Nigeria who had attacked government offices. Many perceived the tweet to be a threat to the Igbo ethnic group in southeast Nigeria. Twitter stated that Buhari’s tweet violated its policy prohibiting content that incites violence. In response to Twitter’s deletion of the tweet, the Nigerian government suspended Twitter operations in Nigeria on June 4, 2021, blocking Twitter users in Nigeria from accessing the site. The Twitter platform, with around three million Twitter users in Nigeria, has served as a critical mode of communication during social movements and protests. In January of 2022, the Nigerian government lifted the ban after coming to an agreement with Twitter.

Use of Twitter by Nigerian Small Businesses

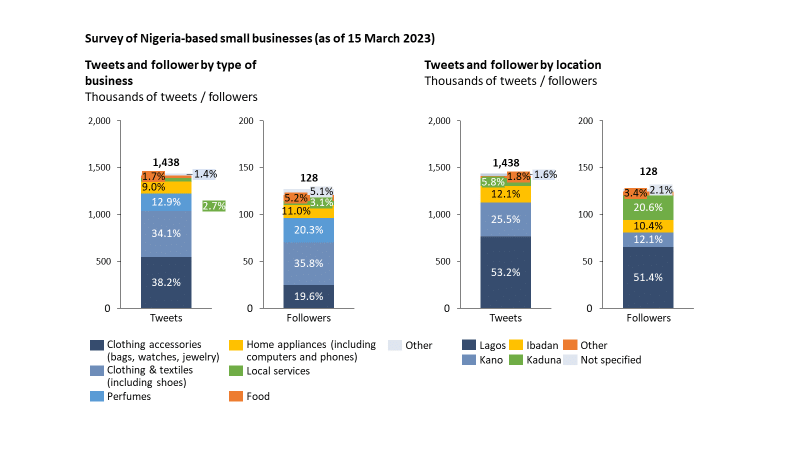

We find significant evidence of rich and extensive use of Twitter by small businesses in Nigeria for a wide variety of business operations and objectives. Figure 6 displays the breakdown of our sample of 10 small business Twitter accounts by type of business. The 10 businesses have collectively tweeted a total of 1,438,000 timesas of 15 March 2023, and have a total of 128,000 followers, indicating significant small business activity on the platform. Small businesses in Nigeria utilize Twitter to market their brands and engage in customer service. The Director General of the Lagos Chamber of Commerce stated that “a sizeable number of citizens” in Nigeria utilize Twitter to make their living.

We find that the 7-month Twitter ban severely limited these small business operations and obstructed the fulfillment of business objectives.

Blocking Twitter directly affects individual businesses, “such as those that make clothing and sell it online... it impacts them personally, and their families personally” (Digital Rights NGO #3)

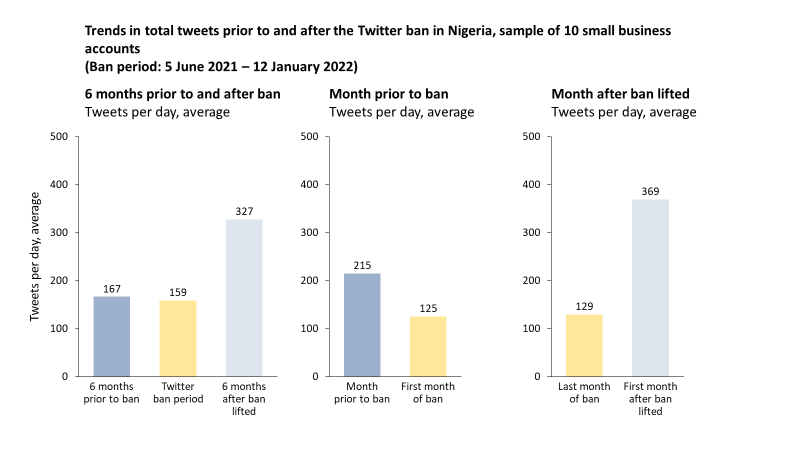

As seen in Figure 7 below, the number of Tweets originating from the 10 small businesses in our sample decreased upon implementation of the ban. During the first month of the ban, the 10 small businesses tweeted a total of 3,865 times total (125 tweets per day), a 42% decrease from one month prior to the ban. Twitter usage by some small businesses continued throughout the ban at a limited scope, likely through the use of circumvention tools such as VPNs.

Government Use of the Platform

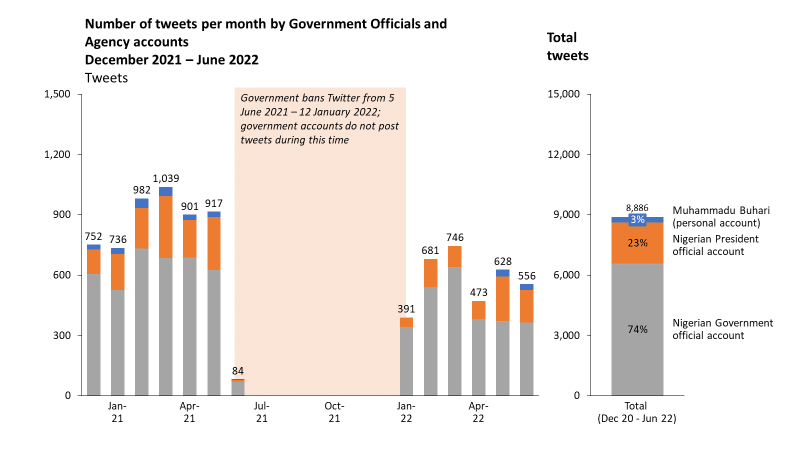

We find that official government Twitter accounts were inactive during the 7-month Twitter ban, in line with the mandates of the ban. That said, these accounts were active users on the Twitter platform prior to the ban and resumed activity almost immediately following the lifting of the ban, as seen in Figure 8 below. This utilization of the platform by government authorities signals their recognition of the platform’s value. The three accounts analyzed are the Nigerian Government account (@NigeriaGov), the Nigerian Presidency account (@NGRPresident), and President Muhammadu Buhari’s personal account (@Mbuhari).

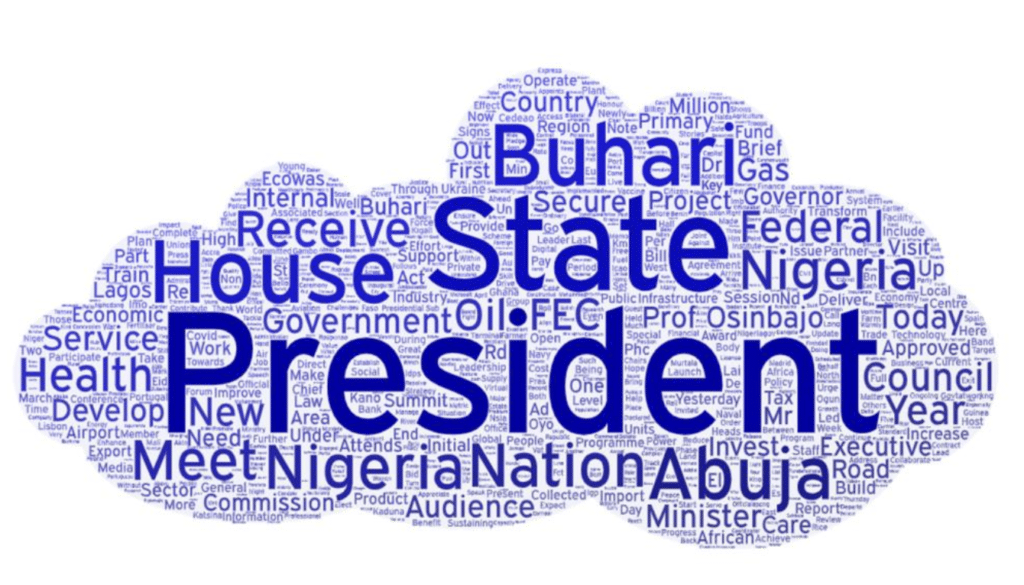

The word clouds depicted in Figure 9 shows the words that appeared most frequently in tweets from the Government of Nigeria accounts between January and July of 2022 (excluding retweets). The official government accounts are used for a variety of official communications. The use of words such as “state”, “secure”, “governing”, and “oil” indicate the use of the platform by authorities to discuss matters about the nation, its economy, and security.

Iran

Scope of digital repression

Internet and telecommunications services are tightly controlled by the Iranian government at every level. The main regulatory body for the telecommunications sector, the SCC, sets most internet-related policies and acts as a “centralized point for policymaking and regulation, effectively minimizing the roles of the executive, legislative and judicial branches and bringing internet policy under the supreme leader’s direct control.” In 2020, the government spent c.$660m setting up the “National Information Network” (NIN), a domestic internet which includes locally built search engines, instant messaging applications, email services, and social media, akin to “China’s Great Firewall.” Since 2021, the government has been working to introduce the “User Protection Bill”, which will extend the authority of the SCC, and ban the use of VPNs to access outside media.

“Across the spectrum of countries, Iranian laws on the internet and social media are the most convoluted with draconian penalties.” (Academic Researcher #1)

There is longstanding precedent for the use of restrictions and shutdowns in response to protests in Iran. Twitter was banned in 2009 following its use as a coordination tool in protests against the results of the elections that year. Iran implemented a nationwide near-total shutdown of internet services for the first time during the 2019 protests following a 50% increase in fuel prices. There were further shutdowns in more recent years, including those in July 2021 and November 2021 in response to chronic water shortages. These shutdowns, which focused on mobile services, excluded access to the domestic, state-controlled NIN services.

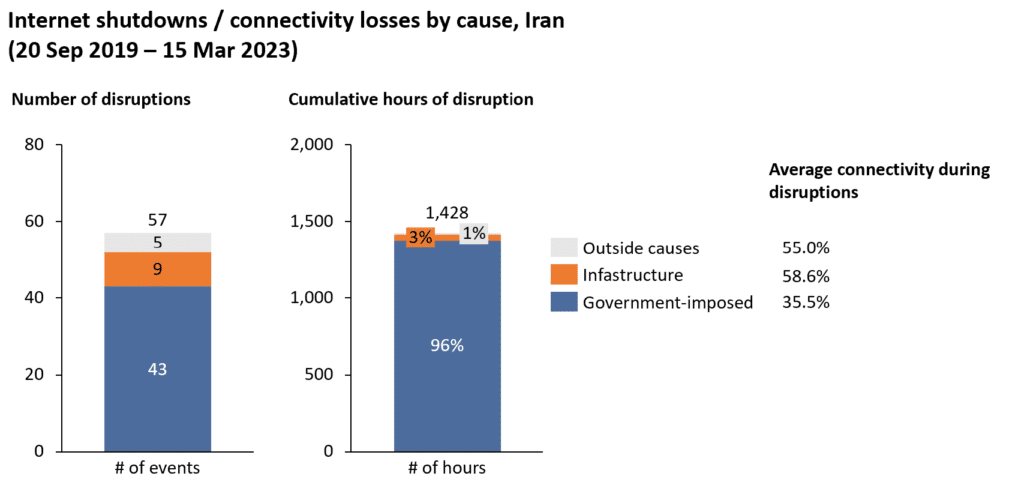

Our research found 57 separate NetBlocks reports on internet disruption in the country between September 2019 and March 2023. These resulted in over 1,400 cumulative hours of disruption. Most recently, multiple internet shutdowns and mobile disruptions have occurred since September 2022 in response to anti-government protests following the death of Mahsa Amini, who was detained by Iranian authorities.

“The government now has control of all ISPs and can shut down the internet at any scale – city, regional and national. Government servers are separate, so even a nationwide shutdown allows them to stay online” (Digital Rights NGO #2)

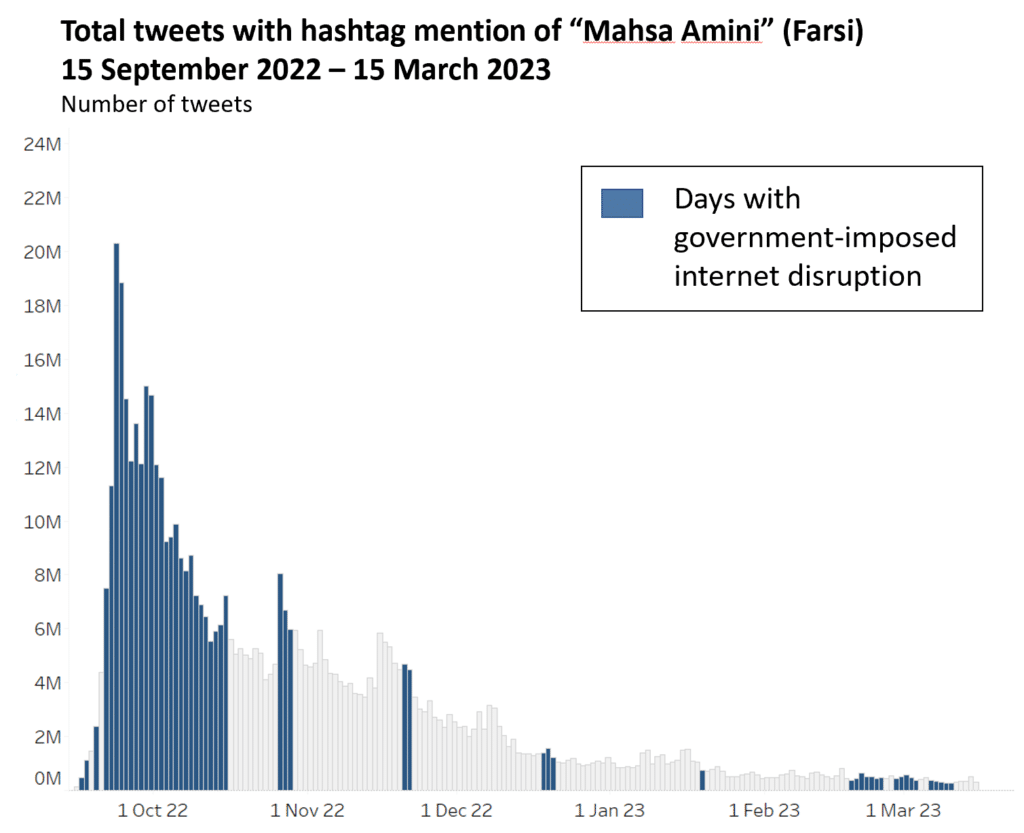

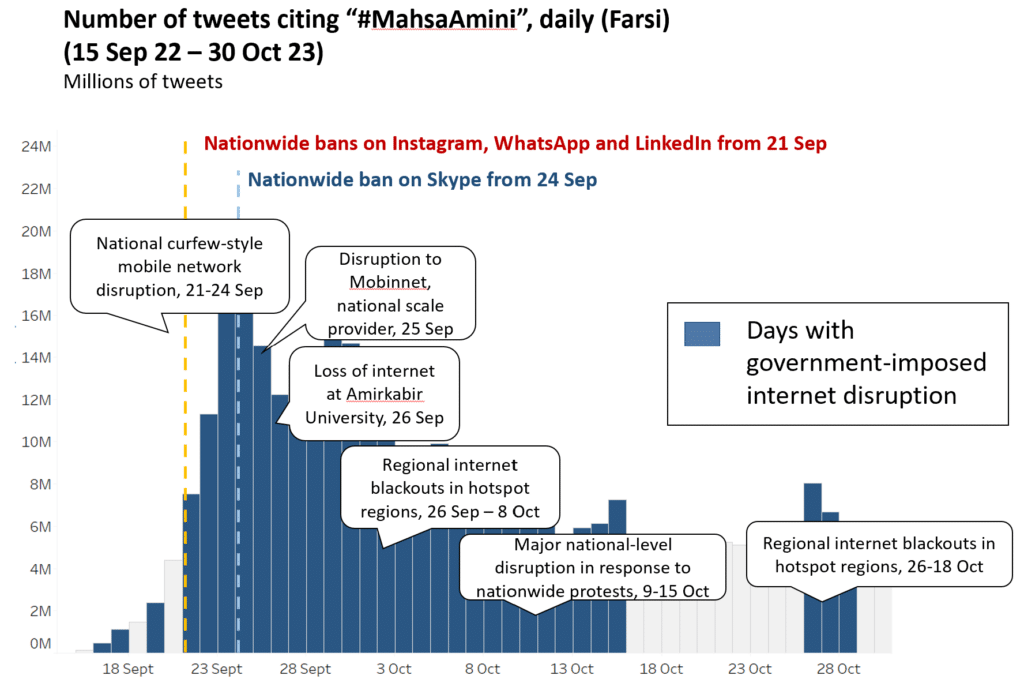

Mahsa Amini Protests

There was a significant response to the death of Mahsa Amini on Twitter, which was sustained in the following months, despite the official nationwide ban on the platform. Alongside this, government-imposed disruptions were introduced as protests escalated both in person and online. Hossein Kermani, an academic at the University of Vienna, highlights multiple use cases of the hashtag. He denotes it as “a powerful discursive attempt to challenge some of the regime’s hegemonic discourse nodal points, such as the hijab”, as part of a broader social movement against patriarchism. Furthermore, Kermani notes the geographical reach of the movement, where “rural areas and small cities joined in a nationwide protest for the first time.”

Though further evidence would be needed to establish causality between the ramp-up in digital censorship and the decreasing use of the hashtag, the intent of the government to censor use of the hashtag is clear. This highlights a tension between a public which sees a benefit in the use of Twitter as a tool to challenge current discourse, and for coordination of social movements, and a government looking to protect the status quo.

Government Use of the Platform

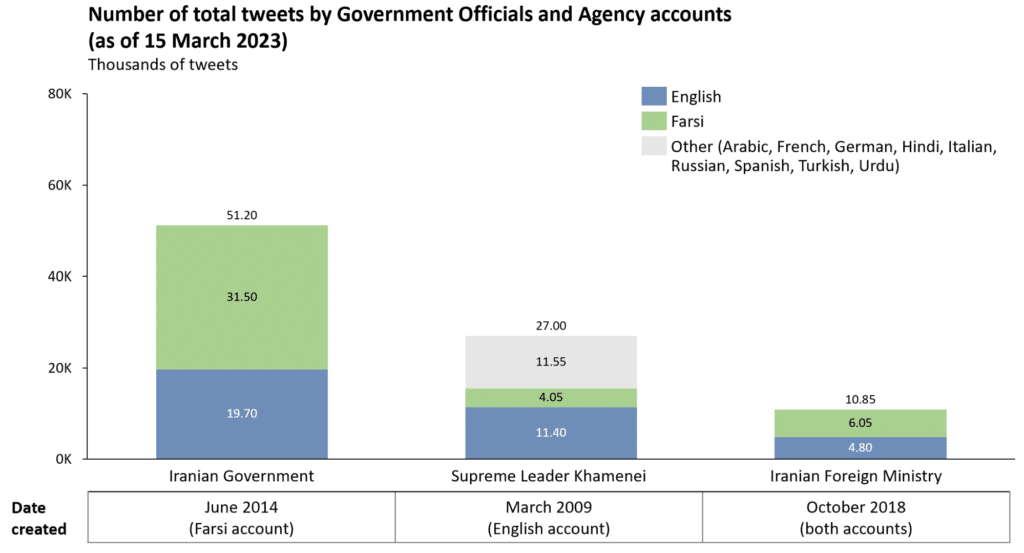

Despite the long-term ban on Twitter, Iranian government officials have long used the platform, and continue to do so. The official Iranian government account is the most active among those surveyed. Amongst officials, the Supreme Leader Khamenei has a particularly significant presence, with ~27,000 tweets across 11 accounts covering a range of languages, indicating an intention to communicate to an audience both within the country and outside the country.

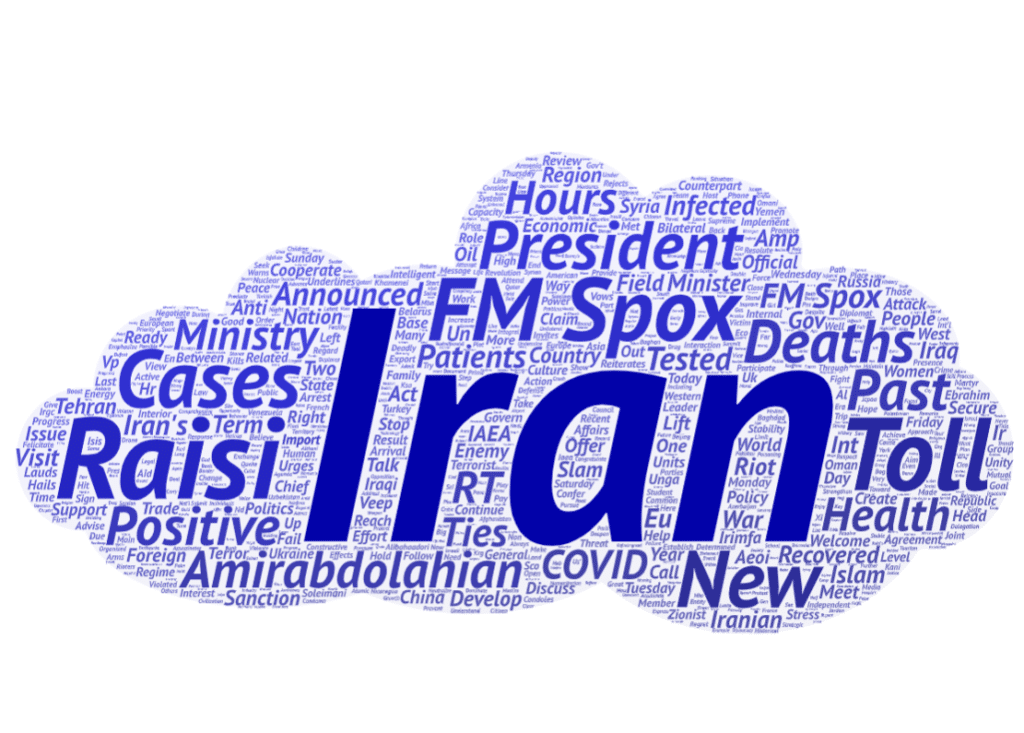

Figure 14 shows the words that appeared most frequently in tweets from the official Government. The account appears to be used for various official communications including the reporting of messages from the President (“Raisi”, “President”), and Foreign Minister (“FM Spox”, “Amirabdolahian”, “Ties”). This includes retweets (“RT”) from other official and personal accounts. The reporting of COVID-19 cases (“New”, “Cases”, “Deaths” “Toll”, “Health”, “Infected”) is a documented example of the account being used to support public services.

This demonstrates that the government sees value in Twitter as a platform to disseminate both political messages and important public messaging, but there is reticence to provide these same benefits to the broader population. Even in circumstances where individuals have tacit approval to circumvent the official restrictions, such as pro-state journalists, they will have to moderate the content they can disseminate, and may find their general usage compromised by broader internet disruption.

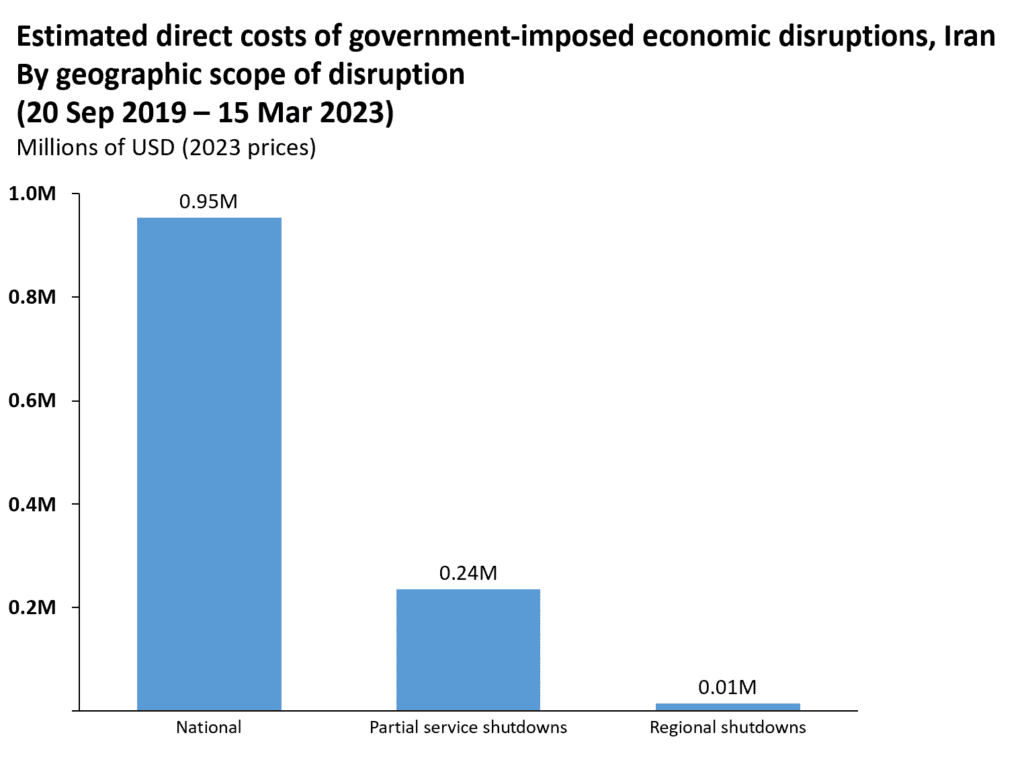

Based on the total duration and scope of internet disruptions reported by NetBlocks since September 2019, we estimate the direct economic cost of government-imposed disruptions in Iran is $1.2bn. Moreover, there are likely to be further indirect economic costs due to employment multiplier effects – for every one job that is lost in the digital economy, a further 1.54 jobs are lost in the broader economy.

Though regional shutdowns account for the most cumulative hours of disruption, we found the majority of costs to come from national scale shutdowns. This reflects the Iranian authorities’ intention to mitigate the economic costs of disruptions through more targeted shutdowns, where only a small proportion of the population, and hence a smaller proportion of the digital economy, is affected.

Targeted shutdowns are made possible through maintenance of access to a more restricted, local internet, which has required significant investment in the underlying architecture from the Iranian government, for instance through the NIN. It also involves blocking wider access to internet services through the use of VPNs.

To maintain this level of sophisticated control over citizen access,there is a broader economic costof shutting its population off from links to overseas users and websites, and the commercial opportunities these could provide. The surveillance that NIN facilitates also represents an intangible cost to citizens, compromising their privacy and security.

Implications

These case studies provide compelling evidence of the benefits Twitter provides to both government actors and the broader population. However, two key risks could compromise these benefits.

The first is the evident conflict of interest between authoritarian governments and their citizens. As documented, despite high levels of activity from accounts owned by government officials and entities, governments will block or restrict access to the platform for their citizens. Preserving national security, stopping the spread of hate speech and preventing mis- and disinformation are some of the reasons put forward as reasons for these restrictions. These are often false pretexts, masking the government's true intentions to restrict the flow of information between dissenting groups.

The most straightforward response would be to challenge government narratives in these scenarios, often themselves steeped in mis- and disinformation. Twitter (X) has the data to debunk these claims and could work independently or in collaboration with external researchers and analysts to do so. Furthermore, the value the platform delivers to governments could be leveraged to encourage freer access.

A simple but powerful instrument to deploy would be the checkmark system. Government accounts in countries that do not provide the same rights of access to their citizens would not receive grey government checkmarks, reducing their credibility. More fundamentally, Twitter can make sure its operations in the country are on its own terms and principles or walk away, as Google famously did in China. This would not be a decision taken lightly, given the costs to citizens of losing the platform, which may be the only available platform for relatively free discourse.

“There are tradeoffs between acquiescing to the demands of a government versus discontinuing operations in that country. In a lot of countries, the government has fully consolidated control over the media environment. These platforms are the only remaining spaces for news, contacting loved ones, and organizing with diaspora communities abroad.” (Digital Rights NGO #X)

The second risk comes from recent developments at Twitter itself. Once known for unfailing uptime and seamless communication, cuts to data storage facilities and technology teams have led to glitches and outages which have frustrated users, and could be especially devastating in a crisis. Furthermore, downsizing teams including Trust & Safety and Public Policy reduces the platform’s capacity to engage with governments and hold them to account. Underlying this is a blasé attitude from Elon Musk, who as noted by former Head of Trust and Safety Yoel Roth, “criticizes the capriciousness of platform policies” while his own form of top-down governance “by edict” is characterized by “impulsive changes and tweet-length pronouncements about Twitter’s rules.” Moreover, Musk’s prominence and hands-on involvement across multiple companies and ventures opens up avenues for conflicts of interest with governments and private sector actors.

This is exacerbated by a new direction in policy that prioritizes short-term profits over longer-term credibility. Blue checkmarks, once the domain of authoritative public agencies, were sold to the highest bidder. The newly complex checkmark system, with separate blue, grey, and gold ticks, and blue ticks not being what they once were, causes confusion and undermines trust. The Twitter Developer Platform, which was used to produce the analysis for this report, was once a ‘best-in-class' example of data transparency. It was monetized at the end of February, cutting off access to many public interest users including academics, public transit agencies, and emergency responders. Without it, this report would not have been possible.

Twitter’s historic role as a “global town square” has brought not only benefits but defined its responsibility as a platform to mitigate harm. Due to recent internal action, this town square is in danger of being cleared out. And in countries with repressive regimes, there may not be anything to take its place.

Authors