Deplatforming Reduces Overall Attention to Online Figures, Says Longitudinal Study of 101 Influencers

Justin Hendrix / Jan 6, 2024

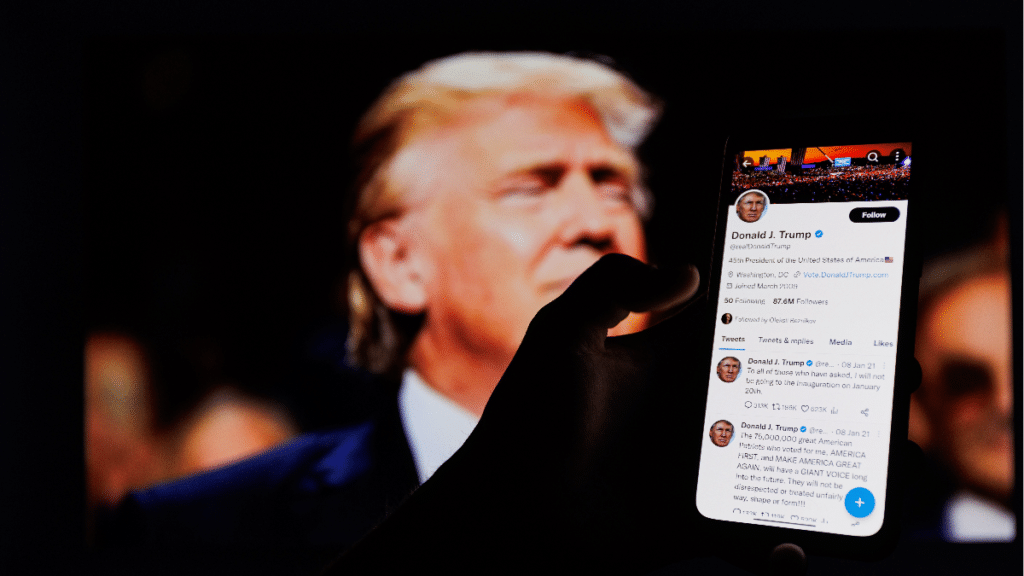

Today is the three year anniversary of the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol. This date also signals the approaching anniversary of series of a subsequent decisions by major social media platforms — including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube — to deplatform former President Donald Trump over concerns that he might use his accounts to continue to encourage violence intended to prevent the transfer of power following his loss to now President Joe Biden in the 2020 US election. Around the same time, platforms and app stores took action against other accounts and social networks implicated in the deadly events in Washington D.C.

Even in the raw, uncertain days after the attack, these content moderation decisions raised concerns among free expression advocates and other experts. How accountable and transparent are platforms about their deplatforming decisions? Does removing problematic personalities from major platforms help fuel the rise of alternative platforms that have even less concern about dangerous speech, and where extremist views may be all the more salient? And does deplatforming actually limit exposure to dangerous speech, disinformation, or incitement to violence?

Prior research on these questions has yielded contradictory findings and indicated the effects of deplatforming are complex. But getting to more granular answers is difficult given limited access to platform data. It is hard to compare deplatforming events across platforms, and often, studies that focus on questions related to deplatforming focus on a single event, or a limited set of them. And, there are various methodological challenges to getting a solid grasp on whether deplatforming actually reduces public attention paid to an individual who becomes the target of what is generally regarded as the most severe content moderation decision platforms can take.

Enter researchers from EPFL Switzerland and Rutgers University, who just published the results of a “longitudinal, quasi-experimental study of 165 deplatforming events targeted at 101 influencers.” The preprint of the study, titled “Deplatforming Norm-Violating Influencers on Social Media Reduces Overall Online Attention Toward Them,” was published to arXiv on January 2, 2024.

To arrive at their results, the researchers first built a dataset, “carefully sourced and annotated at both the entity level (i.e., who was the influencer—a politician or a media personality?) and at the event-level (e.g., why was the influencer deplatformed—for harassment or for spreading false information?).” Then, they measured online attention paid to these personalities, “considering two easily accessible, freely available data sources: Wikipedia pageviews and Google search interest.” The resulting dataset is “the largest collection of deplatforming events (and associated attention traces) to date,” and it is now publicly available for other scholars to study.

The researchers also developed an approach that allows them to “to disentangle the causal effects of deplatforming from the reason behind the intervention,” and to ask more nuanced questions, including:

First, we can better answer the question: does deplatforming reduce online attention toward influencers? Second, we can study whether different individuals are affected differently; e.g., do influencers banned for different reasons respond differently to being deplatformed?

In general, the answer to the first question appears to be a definitive “yes.” Based on the measures developed for the study, the researchers find that in aggregate, after one year online attention towards a deplatformed personality is reduced by 64% on Google and by 43% on Wikipedia.

But, there are important differences when looking at the accounts more closely. Breaking down the set into two groups composed of the most influential 1/3 of the measured personalities and the bottom 2/3 reveals that there is a big difference in the effect for the most well known individuals: “the effect of deplatforming for high-attention entities was roughly 60% lower relative to low-attention entities,” according to the study. So, the more famous (or notorious) a personality, the less effect deplatforming will have on overall attention paid to them.

The study also permitted the researchers to look at different types of deplatforming- including temporary and permanent bans. The researchers observed “similar effects for both temporary and permanent deplatforming,” but note that “users banned for spreading misinformation seem to have their subsequent online attention reduced further than those banned for other reasons.”

The researchers believe their “analysis gives stakeholders (including platforms and legislators) a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of deplatforming.” And, they say, it may provide some support for the idea that temporary bans (such as that applied to former President Trump’s accounts by the major platforms) are preferable to permanent ones:

We find that deplatforming is more effective when targeting popular influencers disseminating misinformation; yet, we argue that the key policy guidance our paper can provide comes from a null result: that temporary deplatforming was similar to permanent deplatforming in how it reduced online attention toward influencers. We speculate that this may be partially due to deterrence, i.e., temporarily banned influencers may avoid rule-breaking to prevent harsher sanctions. Here we did not discriminate between short (e.g., one week) vs. long (e.g., one month) temporary bans, which could be an interesting venue for future work. Broadly, permanent bans of prominent influencers have caused controversy as: the rationale behind the bans is often muddy; there is no clear “reinstatement” procedure for banned accounts; it is unclear if social media companies should be the ones to regulate speech. Having bans of limited time is aligned with the broader call for a more transparent, consistent, and accountable approach to social media moderation.

Interestingly, the singular event of former President Trump’s “great deplatforming” could be regarded as a “confounding event” given “that the online attention received by Trump after his deplatforming would be influenced by both his suspension from major platforms and by the Capitol attack and his reaction to it.” But even in the case of Trump’s removal, the researchers observed a negative effect on online attention paid to him. That suggests their observation more broadly represents a “lower bound” of the effect of deplatforming.

There are still many open questions about the results of deplatforming and the efficacy of other social media content moderation practices that would be better answered if the platforms made it easy for computational social scientists to access data. The researchers argue more comprehensive research is necessary to ensure that “platform decisions are not made in a vacuum or solely to preserve the platforms’ own financial interests.”

I’d add that there are other possibilities to be concerned with— including the political interests of unaccountable platform owners. And, it is just as important to have transparency about decisions to replatform individuals, particularly those removed for incitement to violence. What insight do we really have into the nature of the threat assessments made by YouTube or Meta in their deliberations over whether to reinstate Trump’s accounts? How are we to evaluate those decisions without such insight?

Ultimately, what is needed is “continued monitoring of the effectiveness of moderation interventions,” in particular to “see if there are differences across countries and across years as the digital ecosystem evolves.” With dozens of elections around the world— including a likely heated rematch between Trump and President Joe Biden— there is likely to be a great deal more phenomena to study in the year ahead.

Authors