Creepy AI Crawlers Are Turning the Internet into a Haunted House

Tanu I, Corinne Cath / Oct 31, 2025On Halloween, it is worth considering a threat that is creeping up more silently than the usual seasonal frights but could be far more consequential: Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies are making the internet work less well for its primary audience, people.

Finding information is the top reason that more than 60% of adult internet users go online. Increasingly, the rise of LLMs that underpin generative AI services like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Anthropic’s Claude is fueled by scraping content from the entire internet.

What does this look like in practice? Website speeds slow to a crawl under bot traffic, making information harder to access during breaking events. Publishers set up paywalls to protect their content from extraction, limiting the public’s access to independent journalism. Openly accessible information repositories, like libraries or Wikipedia, are straining under the technical, and hence financial, pressure that AI bot activity is putting on their infrastructure. The list goes on.

These harms all trace back to the same source: AI crawlers. Those automated bots systematically traverse and scrape content from websites, both making it less likely that people will access individual websites (rather than AI generated overviews) and putting significant strain on the internet’s infrastructure and business model. They do so in ways that harm access to information and freedom of expression online. As Dr. Zachary McDowell, an academic expert on the topic, told us, ‘These AI systems are not web crawlers really, more miners. Crawlers are like cartographers, while AI systems are like strip miners.’ The crawlers deployed by companies like OpenAI and Anthropic are extracting vast amounts of content from across the web while contributing little in return. In the process, they are damaging the entire internet ecosystem.

Why this matters now

These AI instigated issues strike at the core of what makes the internet essential, especially during moments when we depend on it most: its ability to let people access and share trustworthy, accurate, and reliable information freely, as well engage in pluralistic public debate. This is not a hypothetical risk; the transformation is already underway. The internet is increasingly functioning as raw material in ‘the production of commercial software’ rather than serving as the key infrastructure for human communication.

The degradation of the internet and market displacement caused by commercial AI crawlers directly undermines people’s ability to access information online. This happens in various ways. First, the AI crawlers put significant technical strain on the internet, making it more difficult and expensive to access for human users, as their activity increases the time needed to access websites. Second, the LLMs trained on this scraped content now provide answers directly to user queries, reducing the need to visit the original sources and cutting off the traffic that once sustained content creators, including media outlets.

Haunted infrastructure: the internet’s broken compact

To understand why this is happening, we need to examine the economic bargain that once sustained the web, and how AI crawlers are shattering it. For decades, web crawlers have been part of the internet’s ecosystem: search engines deployed crawlers to index content, and, in return, they drove traffic back to the sites they crawled. As technology journalists have noted, when search indexing crawler Googlebot came calling, publishers hoped their content would land on the first page of search results, bringing visitors who might click on ads and generate revenue. It was not a perfect system, but it was an exchange: publishers allowed indexing in return for visibility, visitors and revenue.

AI crawlers represent a fundamentally different economic and technical proposition––a vampiric relationship rather than a (somewhat) symbiotic one. They harvest content, news articles, blog posts, and open-source code without providing the semi-reciprocal benefits that made traditional crawling sustainable. Little traffic flows back to sources, especially when search engines like Google start to provide AI generated summaries rather than sending traffic on to the websites their summaries are based on.

The numbers bear this out. Globally, according to some estimates, monthly search engine traffic is down by 15%; according to others, it is more in the 35% realm. Media outlets such as the Wall Street Journal have suffered declines of more than 25%. This decline persists despite serious questions about AI accuracy. Recent research from the Dutch Consumer Protection Association, found that almost a third of Google’s AI summaries were incorrect.

Meanwhile, infrastructure costs increase dramatically, as AI bot traffic strains websites far more than traditional index crawlers.

Through our work at the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and other technical internet governance venues, we help develop technical standards for the internet. In these spaces, we collaborate with engineers, policymakers, and content providers grappling with the crawler crisis. Through conversations with media organizations and digital archives in particular, we observed the impact of AI crawlers firsthand. Understanding the technical mechanics reveals why AI bots are so much more burdensome than traditional search crawlers. And why even in the digital realm, scaling comes at someone’s expense: be it creativity, the climate, or time and skills.

How crawlers work (and why AI crawlers are worse)

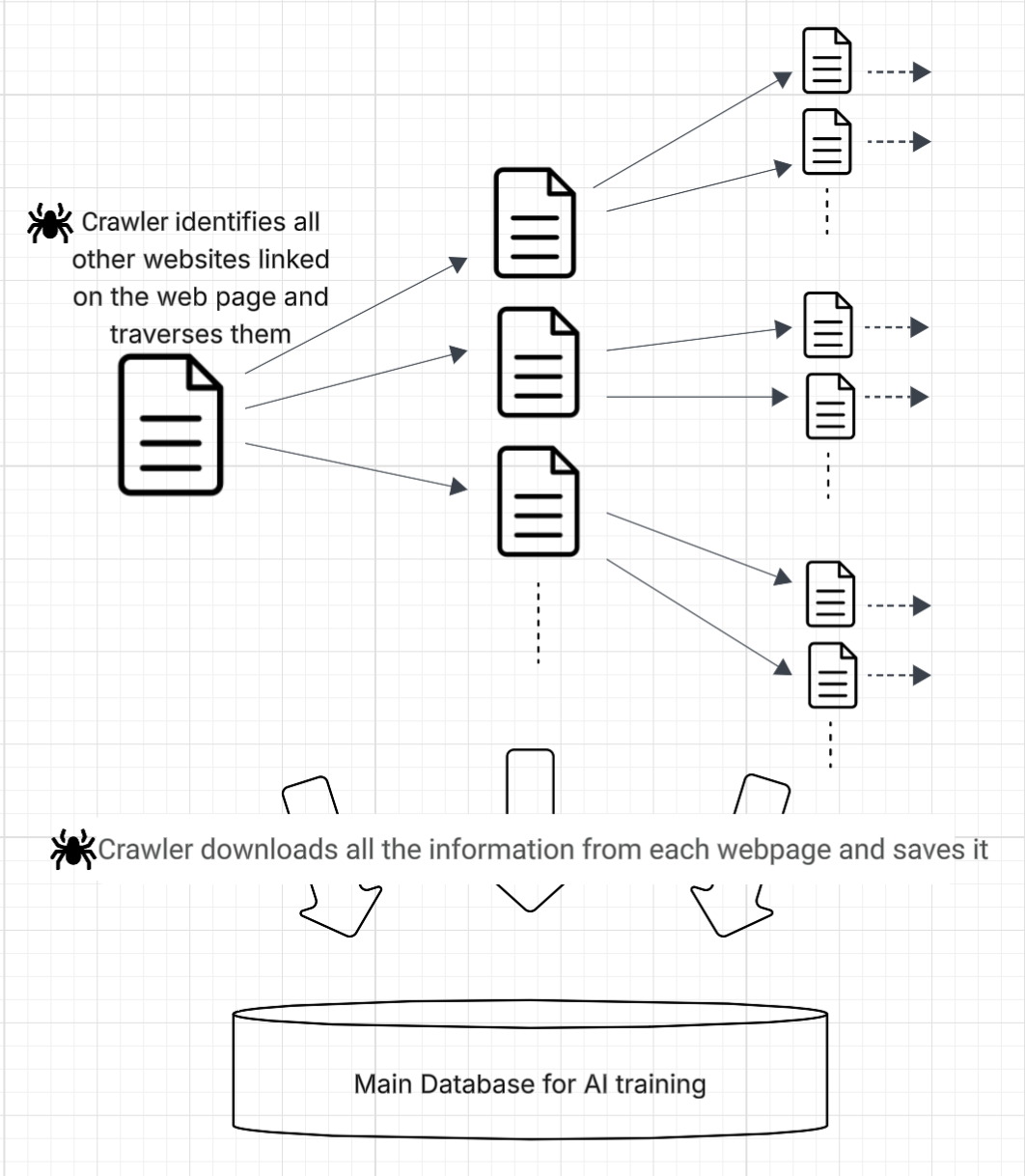

Web crawlers are autonomous software (also called bots) that visit a website, download all its content, and then follow every link on that page to download content from those linked websites. Think of it like walking into a library, photocopying every book on the shelf, and then noticing that each book mentions other books worth reading, so you track down all of those books and photocopy them too, then follow the recommendations in those books, and so on.

The process is iterative: the crawler visits a page, downloads its content (which, after processing, can become AI training data), identifies all linked websites and proceeds to download content from these linked websites, then it moves to the links on those websites and so on. The action continues until the crawler runs out of links or is manually stopped.

The process is illustrated as follows:

Infographic by ARTICLE 19 about how web crawlers work. The document icon is a computer science convention used to represent a web page.

As shown above, crawling is a recursive process that leads to visiting multiple webpages in a very short span of time. It is this process of visiting multiple webpages, rather than the process of downloading content from those webpages (which raises other issues around copyright), that is the most expensive for websites and is making the free internet unsustainable.

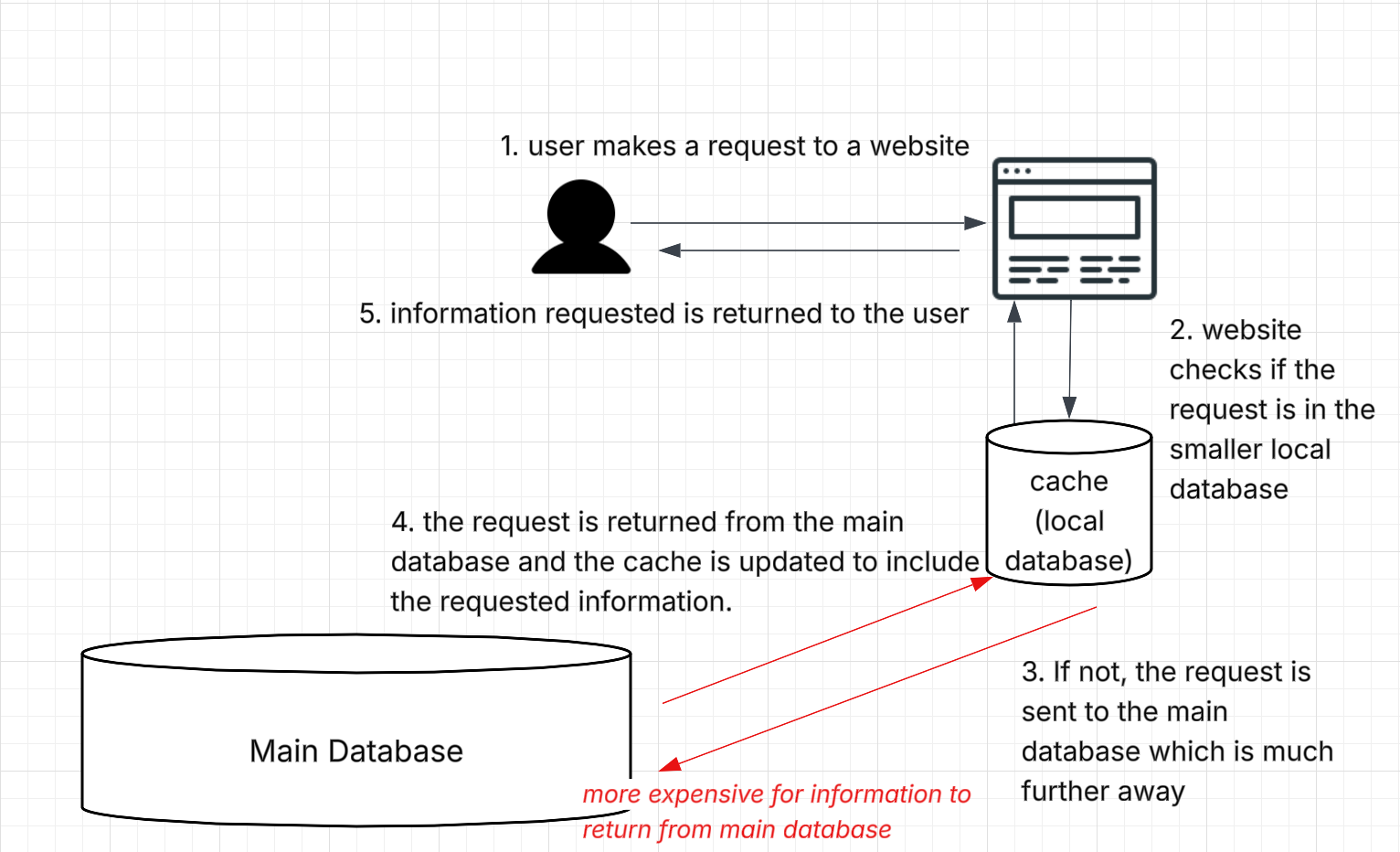

This is because of how requesting information over the internet works. For example, let’s say we want to learn more about ‘Free Speech’ and click on the link to a Wikipedia article on Free Speech. By clicking on the link, we request the information on this webpage from the Wikipedia website. Wikipedia first checks if the requested information is available in its smaller local data center (called ‘a cache’). The cache usually has the most commonly requested information in that region available so as to quickly and cost-effectively return information. Most information requested by humans is usually found in the cache.

However, if the requested information is not found in the smaller local data center or cache, then the request goes to the main data center where all the website’s information is stored. This is more expensive and time consuming as the request/returned information has to traverse further. Most bot traffic gets passed onto the main data center as crawlers visit any link on a webpage, including the less visited ones. When requested information is returned by the main database, the local cache is automatically updated to include the requested information (the oldest requested information in the cache is removed to make space for the new information coming in from the main database). This process of how information requested over the internet is provided to a person is illustrated below.

Infographic by ARTICLE 19 depicting how information requests work over the internet. Most bot traffic requests information from the main database, which is expensive. Whereas most human traffic requests information that is already available in the cache as humans tend to search for popular topics.

This is similar to how a library keeps the most popular books on its shelves, while rare or specialized materials are stored in off-site facilities or regional archives. When you request one of these less common items, the library retrieves it for you, but you will need to wait a few days for it to arrive at your local branch.

Now imagine if malicious actors flooded the system with requests for thousands of obscure materials simultaneously, ten thousand times more than usual demand. These massive, automated requests would overwhelm the library’s retrieval system, slowing down or blocking access for regular patrons trying to check out books, use computers, or request materials for legitimate research.

What makes this worse is that these actors aren’t requesting books to read individual stories or conduct genuine research, they’re extracting the entire collection to feed massive language model systems. The library’s resources are being drained not to serve readers, but to build commercial AI products that will never send anyone back to the library itself. This extractive burden falls hardest on those least able to bear it: AI bots also increase the load times (and are more expensive) for websites with already limited infrastructure, like activist webpages or independent news outlets. Studies suggest that half of users click away if they have to wait for longer than 2 seconds for a website to load. AI bots directly lead to this decrease in human traffic due to increased load times. This is one of the many ways AI bots put a new strain on the internet, degrading its ability to function as an infrastructure for freedom of expression and access to accurate and reliable information.

The human cost of bleeding the web

If this sounds like a horror story, it is, and the victims are real. AI companies are making it more difficult for people to access free knowledge in order to train systems that may eventually compete with those very sources. In the process, they put immense financial and technical strain on the internet. There are some technical interventions, as Audrey Hingle and Mallory Knodel outline in their recent Tech Policy Press piece, “Robots.txt is having a moment: here’s why we should care,” Yet many AI bots disregard robots.txt files, the standard mechanism websites use to communicate crawling boundaries, and access content they have been explicitly forbidden from taking anyway.

This pattern extends across the web. Bot traffic imposes significant costs: hosting fees, bandwidth charges, server strain, degraded performance, as others, including Courtney Rasch, outline. For large publishers or other online information repositories, these costs are manageable, if unwelcome. For smaller outfits like independent journalists or civil society organisations, they can be unsustainable.

When local news sites, nonprofit media outlets, and community organizing platforms shut down or restrict access because they cannot sustain the infrastructure burden, communities lose critical resources for democratic participation. When infrastructure costs become untenable, sites disappear. Archives go offline. Knowledge becomes inaccessible, offered at the altar of speculative AI companies. And if that happens, people lose their ability to access the information they need and share the knowledge they create––the very functions that make the internet essential in the first place.

What can we do now?

The question is no longer whether AI crawlers are disrupting the internet, they clearly are, but what we can do about it. Technical solutions exist, but they are only effective if AI companies choose to respect them; evidence suggests many don’t. Similar concerns hold for market-based interventions that aim to monetise access to content, by centralizing control in unaccountable tech companies.

What can be added to these debates is a clear focus on protecting what matters most: people’s ability to access and share information freely. With that priority in mind, we offer concrete actions for different stakeholders, for the people using, building and regulating the internet and AI.

For technologists and developers:

- Participate in internet governance debates: The IETF and other standards bodies are actively working on protocols for AI crawler and monetization management. Technical public interest expertise is needed to design systems that bring grounded, human rights, perspectives. Your participation matters.

- Discuss and develop open standards: Instead of letting fast moving commercial, centralized gatekeepers become the arbiters of AI crawler content monetization, support the development of open, transparent standards through multi-stakeholder processes at bodies like the IETF and W3C. One place to start is this IETF working group on AI preferences and crawlers.

For policymakers and advocates:

- Government interventions: Competition regulators should investigate the abusive mass extraction of content without adequate compensation operated by AI’s main players, which entrenches their position of power. Governments should provide creative funding mechanisms: The Digital Infrastructure Insights Fund (D//F) and the Sovereign Tech Agency (STA) provide good examples.

- Support public interest infrastructure: Contribute technical expertise and funding to organizations like Wikimedia, the Internet Archive, and nonprofit news organizations that are bearing disproportionate costs from AI crawling, but are also leading the charge in developing alternative, non-centralizing, architectures.

For content creators and website owners:

- Assess your situation: Check your server logs to identify AI bot traffic. Understanding your bot traffic is the first step to managing it. While many AI crawlers ignore robots.txt, some do respect it. Add specific AI crawler user agents to your disallow list. Be aware that this is imperfect: it is a request, not enforcement.

- Consider your technical options: Services like Cloudflare offer tools to block or manage AI crawlers, but these solutions come with tradeoffs. As Luke Hogg and Tim Hwang explain in “Cloudflare’s Troubling Shift from Guardian to Gatekeeper,” consolidating control over who can crawl what content in a single intermediary raises serious concerns about centralized power over information flows.

For everyone:

- Demand accountability: Engage in political debates about AI, the internet, and other technologies in your local and national politics. This is not just a technical issue, it is a question of how we want the internet to function and who it should serve.

- Spread awareness: Most people do not understand that AI crawlers are degrading their ability to access information online. Share this knowledge. The more people understand the stakes, the more pressure there will be for change.

Defeating the monsters: what comes next

This Halloween, the scariest story is not fiction. It is happening right now, every time someone tries to access information online and finds their connection slowed by haunted AI bots serving corporate interests rather than human needs. This threat is easy to miss precisely because it operates in the shadows of the internet, in server logs and bandwidth reports, in the gradual slowdown of sites we depend on.

Unlike seasonal frights that vanish with November, this extraction accelerates daily. The monsters in this story are not fantastical, they are corporate AI crawlers treating our collective knowledge infrastructure as free raw material. And unlike movie monsters, these will not be defeated by daylight, garlic, or silver bullets, but by collective action, technical standards, and policy frameworks that prioritize human access to information over AI production.

Authors