Could Congress Leverage AI to Help Restore Faith in US Democracy?

Lorelei Kelly / Sep 18, 2024

The United States Capitol.

For years, the United States Congress has lagged behind the private sector and other branches of government in terms of its technological capabilities. This digital gap–which impacts everything from basic constituent communication to situational awareness about national security– has disrupted the balance of power among the three branches of the US government, contributing to the growing concentration of authority in the executive and judicial branches, at Congress's expense.

But Congress is also sitting on a tremendous resource that could change this dynamic: communication between members and their constituents is democracy’s mission critical data. This data, drawn from both the lived experiences of citizens and combined with scientific and other forms of expertise produced for and by Congress, could serve as the digital foundation of a modern representative system.

The next step in modernization?

To achieve such a lofty goal will require a great deal of work. The antiquated approach to technology in the legislative branch is a situation years in the making. It took the COVID-19 emergency just to introduce remote video conferencing, and until recently, essential Congressional support offices were using the free version of Zoom. Even at the local level, it wasn't until 2023 that House district offices connected to congressional Wi-Fi. Many Americans feel unheard, and they aren't entirely wrong—Congress, the nation’s most powerful democratic institution, can’t even hear itself. Much of its memory is in boxes in the basement of the Capitol. On a daily basis, Congress struggles to access its own records and adapt to the modern world.

This decline in Congress’s effectiveness isn’t accidental; it’s the result of deliberate choices. Information sharing has consolidated into party leadership, made worse by polarization. Outdated perspectives and traditions persist in this 235-year-old institution, and Congress has stubbornly refused to invest in itself, stalling the development of its digital infrastructure.

Fortunately, this troubling situation is starting to improve. Since 2019, Congress has begun updating and reforming itself through institutional modernization. A bipartisan committee passed 202 recommendations, and now a Modernization Subcommittee and a Fix Congress Caucus are working to implement these changes.

Currently, Congress has 441 members, including 435 elected from the states and 6 that represent US territories in a nonvoting capacity. Presently, each manages their own data independently. Modernization reforms have started to address this challenge with the help of a Congressional Digital Service and collaboration with civil society groups in the “Fix Congress Cohort.” Additionally, Congress is beginning to keep pace with AI advancements by creating a skills-based ecosystem, experimenting with AI in its workflows, establishing guidelines, initiating a member-led AI task force and providing training to staff.

Building on these efforts, Congress now has the chance to take a bold leap into the future. If its leaders so choose, Congress could play a key role in the emerging public AI movement, and build a platform to improve its own functions and American democracy itself. Here’s how it could work.

Building a model for democracy

As the central institution of representative democracy, Congress generates vast amounts of data every day and oversees a large national archival network. Putting this information to work has never been a more compelling prospect given the convergence of data processing and artificial intelligence technologies.

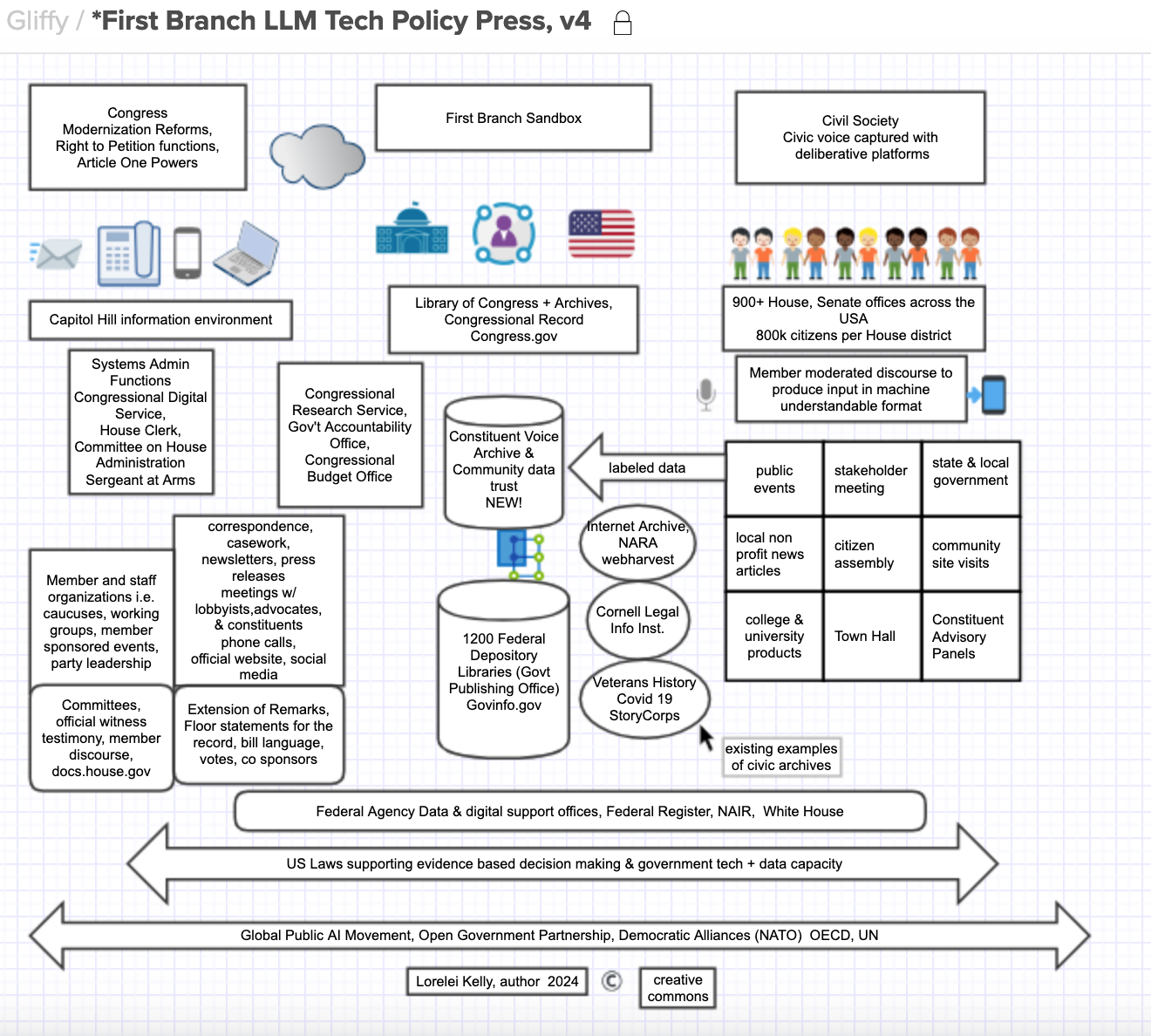

The First Branch LLM (Large Language Model) concept map below imagines the critical infrastructure needed at the enterprise level to create an accessible, accountable, and permanent information system for both the public and lawmakers. This system would also help create a more inclusive record for clearer statutory interpretation, which is especially important after the Supreme Court's recent decision to overturn Chevron deference.

A notable feature of this concept is the inclusion of constituent voices, which is now possible due to advances in nonprofit deliberative technology and voice-to-data capture. Using AI tools to optimize this public-serving data is a major challenge for the 21st century, but it holds the potential to transform how Congress functions and serves the public.

Illustration provided by the author.

The shapes on the left side of the above diagram represent the various information sources for an individual member of Congress as they go about their workday on Capitol Hill. Each of these sources generates a constant stream of data, but the problem is that much of this data is unstructured and isn't organized in a way that makes it easily accessible for collective use in lawmaking. For example, every member, regardless of political affiliation, handles issues related to veterans, social security, and federal grants. The anonymized data from these cases could be part of a shared resource that all members can access.

In the center of the diagram is the "First Branch Sandbox," a space filled with creative opportunities to redesign and improve how Congress manages and shares data crucial to American democracy. The First Branch has vast archival resources, such as Federal Depository Libraries in every state and the Library of Congress, which already holds topic-specific civic voice archives like Veterans and COVID-19. Libraries are trusted sources of information, and their role in supporting Congress should be brought up to date. .

Digital collaborations like the Internet Archive’s webharvest and Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute are excellent examples of using congressional data effectively. A similar approach could be applied to collecting civic voice data from public gatherings led by members of Congress. This data could then be organized and made accessible, similar to a "Congressional Record" for the general public. This would integrate community input into the legislative process, improving deliberation and enhancing Congress's ability to fulfill its First Amendment Right to Petition duties.

In an era of low trust and extreme social polarization, a people-centered First Branch LLM could help restore legitimacy to democratic government. While elections are the ultimate form of accountability in democracy, a Constituent Voice Archive would provide a way for members to receive feedback and make adjustments outside of election cycles. As local data becomes more valuable and productive, it would create incentives for members to better represent all constituents, not just voters and campaign donors.

The shapes on the right of the diagram illustrate how civil society contributes to developing the First Branch LLM. The information that members of Congress gather from their local communities—referred to here as the "district water cooler"—is very valuable but often poorly organized for use in policymaking. The diagram shows how members of Congress can meet with their communities to collect authenticated feedback or advisory data. Deliberative platforms are already being used for this purpose, organized through networks like the Council on Technology and Social Cohesion.

From imagination to implementation

Members of Congress, in collaboration with nonprofit organizations, have already started experimenting with these methods. For example, Georgetown’s Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation piloted a community-informed data gathering method in New Hampshire, and the Popvox Foundation worked with the House Natural Resources Committee on a collaborative editing pilot focused on Environmental Justice legislation. The next step is to create a publicly maintained digital space where this community-generated data can be stored and accessed. A "data fabric" architecture is a promising model for organizing data in a complex system like Congress.

The private sector provides many effective examples of data architecture that support geographically diverse and complex organizations. We can learn from these models to create an enterprise system that strengthens American democracy. The First Branch LLM is a conceptual plan for such a system, and while it's achievable, it will be costly to implement. Currently, Congress has a $10 million innovation fund that, despite being understaffed, is making remarkable progress with its extensive mission. Both in Congress and the private sector, financial constraints can drive innovation, but in Congress, this innovation should also focus on improving public access.

Public access is crucial for restoring trust and legitimacy in democracy, so modernization is a necessary investment in the success of the American experiment. Democracy is at risk both in the US and globally. When institutions like today’s Congress seem ineffective, the appeal of authoritarianism as a means of restoring order grows. We must do everything we can to prevent this outcome. The First Branch LLM is just one idea, and it should spark a broader national conversation about democracy, technology, and how we do the work to protect a shared and prosperous future.

Authors