Compromised Information Environment Casts Doubt on the Fairness of India's Elections

Manasa Narayanan / Apr 18, 2024The big elections are upon us. Starting this week, Indians will vote to elect representatives to the lower house of the Parliament, and choose the prime minister for the next five years. The elections will happen in stages, spread across the next month and a half, with nearly a billion people set to vote.

The sheer scale and complexities of the voting exercise, not to add the high voter turnout the country usually sees, have always invited awe on the global stage. This time around, given the number of Indians expected to cast their votes, it is being touted as the biggest democratic exercise ever to take place on the planet. But serious concerns remain as to how free and fair these elections will be, and what would be the state of democracy and the media if the current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, wins a third term.

Along with suspending two-thirds of opposition MPs and passing bills in their absence, jailing key opposition leaders right before the elections, using tax authorities to freeze funds of the main opposition party, targeting student leaders and activists, and buying out the financial elite in the country, the party leading the Union government, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with Modi at helm, has also captured most of the mainstream press and driven out several critical journalists, along with passing a string of laws that now give the government enormous power over the social media space.

So, with the country’s information landscape having become a casualty in recent years, is there really a level playing field when it comes to election campaigning and messaging? And with misinformation so rife in India, does the average voter today have the necessary information to make a democratic choice?

The same, but more sophisticated

Certainly, circumstances have changed since the last national election in India, in 2019. “You have an entire ecosystem which is much more efficient than what was in 2019 in terms of its ability to spread certain kinds of misinformation,” says Dr. Joyojeet Pal, Associate Professor of Information at the University of Michigan.

In 2019, a lot of the infrastructure to deliver disinformation already existed. So, in many ways, what we are seeing this time around is an extension and expansion of the same tactics. But there are some key differences that tell an important story about where India’s information space is headed.

Dr. Pal explains that, as in the prior election cycle, WhatsApp remains one of the main sources of misinformation in India. But the level of granular data and insight collected now, especially about people’s preferences across platforms, has made WhatsApp operations much more methodical. “Now you can tell explicitly on YouTube what parts of a video are going highly viral compared to other parts of the video. This allows you to figure out what pieces are particularly tugging at people’s emotions and decide, based on that, what you want to turn into WhatsApp videos.”

“Alongside the mechanics of what makes it easier for somebody to figure out the likelihood of virality, which is eventually what drives certain kinds of misinformation, what you also have across political parties and citizen groups, is a very high degree of WhatsApp use as a means of organizing,” he added.

WhatsApp usage is indeed very high in India; with networks of WhatsApp groups percolating all the way down to the booth level (a booth referring to a group of residents assigned to a particular polling booth). This seems to hold true for most political parties now, who are learning from the BJP playbook. While WhatsApp was used by campaigns before, more political parties are choosing to hire political consultancies to run elaborate social media campaigns.

In a phone interview, Swarnim Chaturvedi, Rajasthan’s General Secretary for the Congress party, says that they are running a dedicated campaign via WhatsApp in the state. There is a “war room” at the state level that decides on the campaign messaging, Chaturvedi explains. This team then relays the strategy and campaign materials to the various assembly constituency teams, which eventually reaches booth-level volunteers, who are responsible for getting these messages to the voters. He says volunteers run both in-person events and also pass on information via social media channels, which includes making use of local WhatsApp groups.

Chaturvedi further says that in the state of Rajasthan, the campaign’s messaging has revolved around pointing out policy failures of the BJP-led central government. I could not independently confirm this, and a lot is unknown about the kind of information trickling down via these groups.

But while many political parties, on the state and national level, have joined the WhatsApp bandwagon, the scale and money thrown behind these operations, as well as the kind of offensive operations run by the BJP, seem unparalleled.

As investigations before have pointed out, the Modi-led BJP carried out vast disinformation and hate campaigns in the run up to 2019 national elections, as well as before several state elections in subsequent years. The party was the first to tap into the vast WhatsApp user base that existed; not only making use of people officially running campaigns, but hiring third-party actors to run shadow operations.

The world of shadow operations

While investigating the scale of such operations is difficult on WhatsApp (although a certain BJP supremacy is clear, at least on the national level), on platforms like Facebook and Instagram, where the content is publicly visible and there is greater transparency on the kind of political messaging being done and money thrown behind it, it is very clear that the playing field is not level. The BJP continues to have an upper hand.

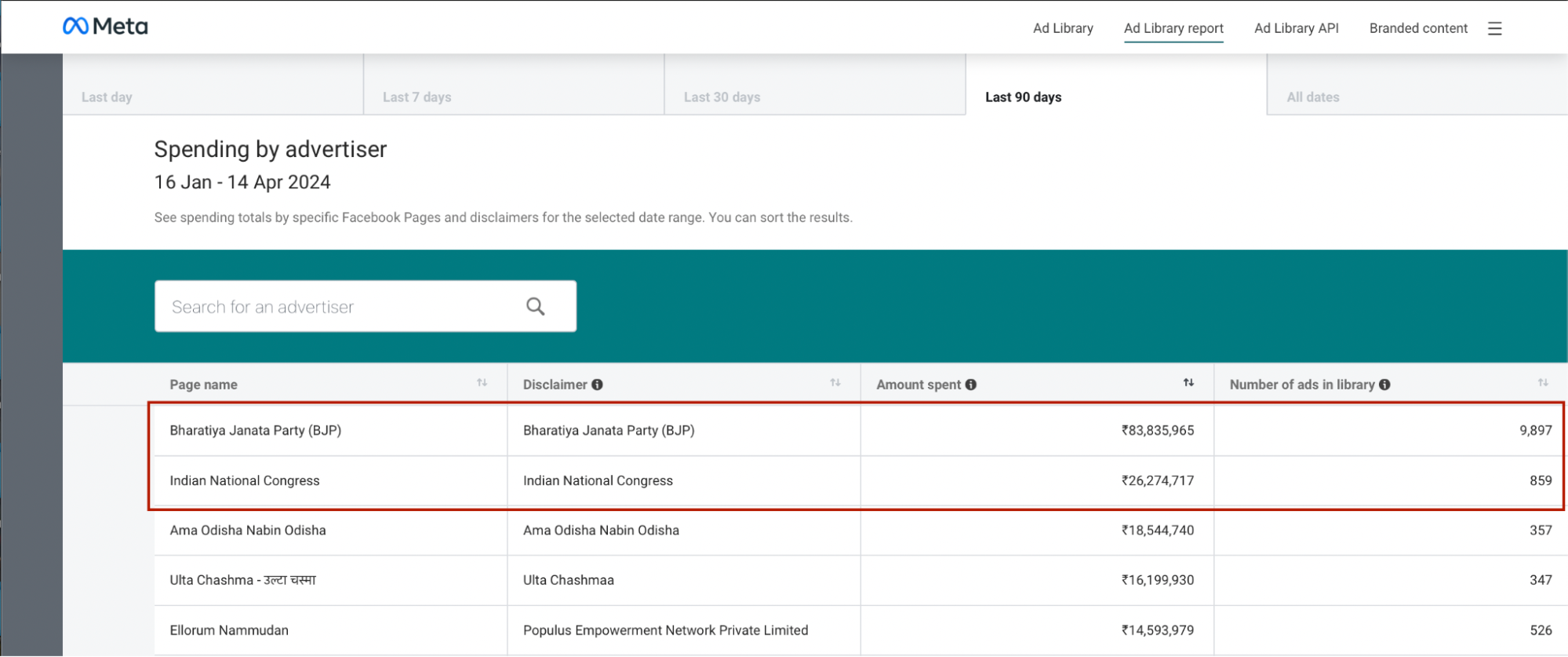

If one looks at Meta’s ad library records, in the last 90 days alone, the BJP’s official campaign has spent ₹83 million ($993,000 USD) on political advertising on the platform, having put out 9897 ads. The Congress on the other hand spent around ₹26 million ($311,000 USD), less than one-thirds of the BJP, putting out 859 ads. But the spending by official campaigns doesn't even begin to show us the real picture. Most of the offensive and decisive operations are run via shadow and surrogate advertisers.

Screenshot provided by the author.

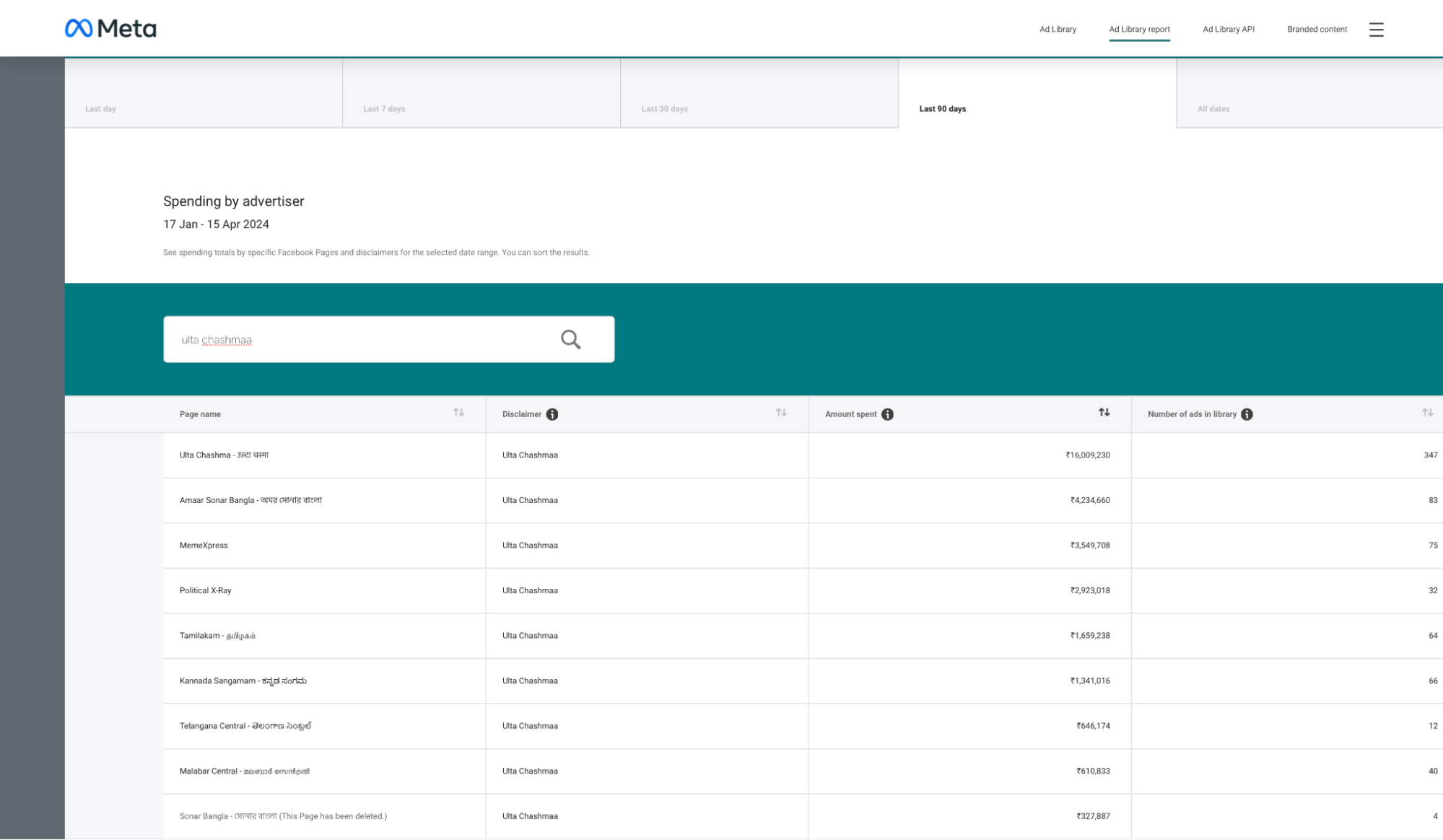

A recent BOOM Live investigation showed that a shadow network of pro-BJP pages has spent something like ₹20 million ($239,000 USD) on political ads on Meta, several of which feature hate speech, disinformation and propaganda. This spending accounts for the ads put out in the last four months, from November 2023 to March 2024. Under the banner “Ulta Chashmaa,” there are nine pages that do this (with one page having been deleted and eight still active), none of which have currently been linked to the party directly.

Screenshot provided by the author.

But the reason their origins are hard to trace and connection with the political party difficult to establish is because pages like these obscure owner information. They create empty placeholder websites, and give out fake numbers and addresses. So despite Meta requiring pages running political ads to go through “verification” under its transparency rules, these ghost pages have continued to exploit the ad space through a process ridden with loopholes.

Critically, one significant difference between the shadow pages this time around to the 2019 national elections, is the very visible push to target Southern states and voters with pro-BJP ads. Four pages in this network are dedicated to Southern Indian languages (Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada), and these pages target state-specific opposition parties and leaders. This is in line with the BJP’s official campaign this time to campaign heavily in Southern India where the party doesn’t have a loyal voter base the way it has in several Northern Indian states.

Karen Rebelo, the journalist who carried out the investigation into the “Ulta Chashmaa” network, tells me that she did reach out to Meta before the story was published, but did not hear back from the company. After the story was published, she says Meta told her that it had removed a couple of posts she had flagged for hate speech, but then did not act on the surrogate pages themselves that appeared to be flouting Meta’s rules on political advertising.

This is only one network though. Research published this week by Ekō, Foundation London Story and India Civil Watch International reveals the actual scale of far-right shadow operations being run on Meta. They found that ₹83.5 million ($1 million USD) has been spent on shadow advertising on Meta in the last 3 months by far-right pages. This accounts for about 22% of all political ads run in India in that time. And importantly, the money behind this shadow operation is larger than the BJP’s official campaign spend on the platform in the same time span.

Adverts put out by these far-right pages feature hate speech, smear opposition parties and candidates, and promote Hindu supremacist narratives. The research found that several ads pushed by this network also break the Indian election laws.

According to the guidelines set up by the Election Commission of India (ECI), mandated following a Supreme Court decision in 2004, all political ads during the election period need “precertification” from the ECI before they are put out. And the ECI has clarified that this extends to social media too. Alongside this, the Model Code of Conduct, which comes into action the day election dates are announced, prohibits ads that “promote enmity on grounds of religion,” among other things. So not only do these ads evade Meta’s rules, they also break the Election Commission’s regulations that have been put in place to maintain a level playing field.

“Platforms facilitating shadow advertising that seek to promote a decisive narrative, and that do not allow a normal voter to see who is actually behind these ads, is undoing all the progress India has made towards election integrity,” said Dr. Ritumbra Manuvie, who is an Assistant Professor of Law at University of Groningen and also co-founded Foundation London Story, a nonprofit that researches hate and disinformation online.

The issue of shadow advertising is not a new problem. In fact, back in 2022, a Reporter's Collective and ad.watch investigation showed that over the span of almost two years, the BJP secretly funded many ghost and surrogate advertisers on Meta to target the opposition in various state elections, spending ₹58.3 million, and amassing 1.31 billion views. In contrast, the Congress spent ₹2.3 million, which is less than 4% of what the BJP spent.

At the time Meta said it applied its rules on “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” uniformly. But as the investigation showed, while Meta seemed to have removed several hundred pages linked to the Indian National Congress in the run up to 2019 elections, many of the pages linked to the BJP continued to run adverts over the years, facing no action. This time around as well, Meta has failed to remove the pro-BJP shadow pages violating rules.

Should we worry about deepfakes?

Other than an intensification of campaigning using social media channels and more unchecked use of shadow advertising, the obvious difference between 2019 and now is the use of AI, particularly deepfake technologies. While several state elections in the country in the last couple of years saw use of deepfakes, this is the first national election in India since generative AI tools became widely available for public use.

“There’s been a lot less of the adversarial AI that we were afraid of at the start of this whole creation of LLMs and video generation tools. Which is to say, rather than a slew of fake videos of politicians saying things which they didn’t, you have the opposite – which is politicians authorizing videos of themselves saying things in certain ways to make them[selves] look positive,” says Dr. Pal.

While worries of sinister uses of AI do seem exaggerated at this stage, Archis Chowdhury, a senior correspondent at BOOM Live, believes that we will still see them this election cycle. “There’s a lot of attention on deepfakes right now and so they don’t have a very long shelf life on social media platforms. So if they show up, they’re going to be taken down, which is why it’s most effective to put them out on the day of polling or just before,” he explains.

Having tracked the use of deepfakes in recent elections in neighbouring countries, he believes that more harmful deepfakes will appear in India at the eleventh hour. “Bangladesh and Pakistan, both on the eve of elections, we saw… deepfakes go viral on social media and then were taken down immediately. But they got super viral before [they] got taken down. And they showed these independent candidates saying they’re going to boycott the elections, asking their supporters to not vote... [In Pakistan] we saw Imran Khan’s party, including a deepfaked Imran Khan saying that they’re going to boycott the elections. And this was happening parallel to Imran Khan’s party themselves using a deepfake to spread Imran Khan’s message because he was in jail.”

A dangerous concoction: Digital influencers, friendly platforms & draconian laws

Adding to the already terrifying environment of online hate and disinformation, shadow networks, and deepfake technology, political parties in India are now also making use of digital influencers, bypassing journalists and having to face any critical questioning.

Explaining the increased reliance on influencers, Dr. Pal says, “Because news is so polarized in India, it actually doesn’t benefit a politician tremendously to go and show themselves on a mainstream news channel, because the people who follow mainstream news channels have already decided which end of the spectrum they’re on and so they’re not about to be converted. The influencer on the other hand is somebody who, let’s say, reviews mobile phones or some food culture, and as a result they have followers from across the political spectrum. So you can go on an influencer’s channel and actually convert people.”

The BJP in particular has adopted the influencer model for a lot of its communication, with top ministers not only appearing on various influencers’ channels, but also with the Modi government now publicly promoting and elevating influencers by setting up a National Creators Award.

“An influencer who interviews you is quite likely to be comparatively less competent at a political interview than someone who is a political journalist who knows what policy questions to ask… particularly benefits politicians [as]... you can present an alternative picture of yourself, somebody who’s at home with their children, out and about eating food… so it humanizes a politician,” adds Dr. Pal.

But not online influencers seem to be getting on the good books of politicians. There is now a particular segment of online creators — journalists who were with the mainstream press or with digital news outlets in their previous lives — who have since moved to YouTube and Twitter to produce content. This class of more critical influencers are now increasingly under attack now from the new set of information laws that have come into force in the country.

Speaking about the IT Rules 2009, and amendments to it with the IT Rules, 2021, Saurav Das, an independent journalist who covers legal affairs and policy, who also produces online content in the form of explainer threads on X, says that these laws do not allow for transparency in the content takedown process. So the government has been using this legislation to arbitrarily force platforms to take down not only pieces of content, but entire channels without having to provide any explanation to the users or citizenry.

Just in the last month, the government directed YouTube to take down National Dastak, a news channel with 9,410,000 subscribers. It forced Facebook to restrict the page of Article 19, an Indian news site, and also got Bolta Hindustan’s YouTube channel taken down. All of this occurred without providing any reasons to the outlets.

The reason the BJP-led government is able to do so is because of a confidentiality clause in the law, Das points out. “The rules state that all of the action that the government takes in pursuant to a complaint that it receives has to be strictly confidential. Now, the government interprets that to mean that everything from the beginning to the end, including the order, the notice and all actions… is covered within that exemption clause.”

“The experts say that only the person who has complained to the ministry for seeking action against someone, the identity of them has to be kept secret. Not the notice, not the final order that the ministry passes and not the review committee.”

Das says that more transparency needs to be introduced in the process so that users affected by the law understand the circumstances under which their content or channels have been taken down. Otherwise, governments can continue to use the law with impunity. “The government, the executive, then becomes the judge, jury, executioner,” he says.

Very importantly, Das also points out that the central government is misusing emergency power provisions in the law, which it is using to block content immediately, without even having to follow the little process there is. This was the provision used last year when the government banned a BBC documentary that explored Modi’s role in the 2022 Gujarat riots.

Other than the IT Rules, the government also passed the Telecommunications Bill in 2023, which gives it broad powers. Ambiguity built into the law means pretty much any digital communication technology can fall under “telecommunication services,” and is therefore subject to government action.

“The law empowers the government to prescribe guidelines that these telecommunication services will have to follow. And if they don’t follow, then they’re going to lose their license.” “Experience has shown that they’re usually not in favor of the right to privacy. And, you know, breaking encryption… the government has been attempting that for a very long time. And this law, because it’s so ambiguous, it could potentially include all these encrypted platforms,” Das added.

This is more concerning now because the US based social media platforms operating in India have grown increasingly cosy with the Indian government. “Facebook, I think, was always more accepting of government orders. But then you saw Twitter actually put up a fight sometimes. But then after Musk, I see that is not working here.”

So while a growing class of friendly influencers are not only benefiting from political capital but also platform engagement, propelling their voices further, critical, important reporting from other influencers is in serious jeopardy.

An unlikely democracy, fighting or flailing?

Writing in 2007, the well-known historian Ramachandra Guha called India “an unlikely democracy,” underlining the point that while many expected the country’s experiment with democracy to fail, owing to its vastness and diversity, India has still held on. Guha gave five points for this success, one among them being the presence of a “free press,” something that has come under serious threat as this piece outlines.

Interestingly, he also named “the vibrant Hindi film industry” as a positive influence on Indian democracy. But as many commentators have noted off late, the space for criticism and diverse views is shrinking in the world of pop culture too. Many in the Bollywood film industry seem sold out to the idea of Hindutva, not to add that a string of films driving the Hindutva fervor have lined up for release in the lead up to these elections. So, given the slow demise of spaces for open cultural exchanges and debates, would our “unlikely democracy” remain a democracy? Or will the cynics be proven correct now that India’s pluralism is in jeopardy?

As for now, millions of Indians do have the vote. And millions will vote in this election. And there are several critical and brave voices, that despite the threats and challenges, are fighting for India’s deliberative soul to be preserved.

What is left to be seen is whether these critical voices can reach the grassroots despite the government and digital media environment being stacked against them. And more importantly, it is an open question whether the case for a deliberative, open, and tolerant society will be accepted by the larger citizenry. When the results are in on June 4th, the answers should become clear. For now, we will have to wait.

Authors