Civil Unrest and Social Media Regulation in the UK

Tim Bernard / Aug 21, 2024

July 30 2024, United Kingdom: Riot police in front of burning police van in Southport. Ian Hamlett/Shutterstock

Social media has been widely implicated as a key factor of the anti-immigrant riots that spread throughout the United Kingdom in late July and early August. Far-right agitators and opportunist conspiracy theorists appear to have deliberately appropriated the tragedy of a stabbing at a children’s dance class, spreading misinformation about the identity of the attacker online and encouraging and organizing violent attacks. Elon Musk is personally embroiled in these events, posting both temperature-raising pontification and (later deleted) outright misinformation, leading to calls for him to face direct consequences. (At the same time, Musk is under investigation by French authorities for cyberbullying Olympic athlete Imane Khelif.)

Ofcom and the Online Safety Act

Ofcom, the British regulator tasked with regulating social media companies under the recently passed Online Safety Act (OSA), responded to the situation in a short online update and an open letter to the platforms. These explain the two ways that, once the Act comes into force “later this year,” social media companies may have to take actions to impede the spread of the kind of content that incited the recent civil unrest:

- When regulated services have “reasonable grounds to infer” that content is illegal, they will be required to remove it. What that will mean in practice is far from straightforward, with Ofcom’s consultation guidance documents on the duty amounting to over 1700 pages.

- Larger platforms will be required to consistently apply their own rules for content moderation (a similar duty is already imposed by the EU’s Digital Services Act). Mainstream platforms like Facebook, and even X, do prohibit the incitement of violence and racial hatred (on X, at least when this is associated with violence). Facebook also asserts that it will remove misinformation “where it is likely to directly contribute to the risk of imminent physical harm.” Here again, though, the application of these rules is not always clear, especially in a situation of emerging threats, and may not include coded or implied calls for violence.

There are also services, most prominently in this case, Telegram, that have much looser (or practically non-existent) content policies. They may also be difficult to regulate with no official presence in the UK. Furthermore, a known problem in content moderation is the linking from mainstream platforms to less-moderated platforms where the most clearly problematic activity takes place.

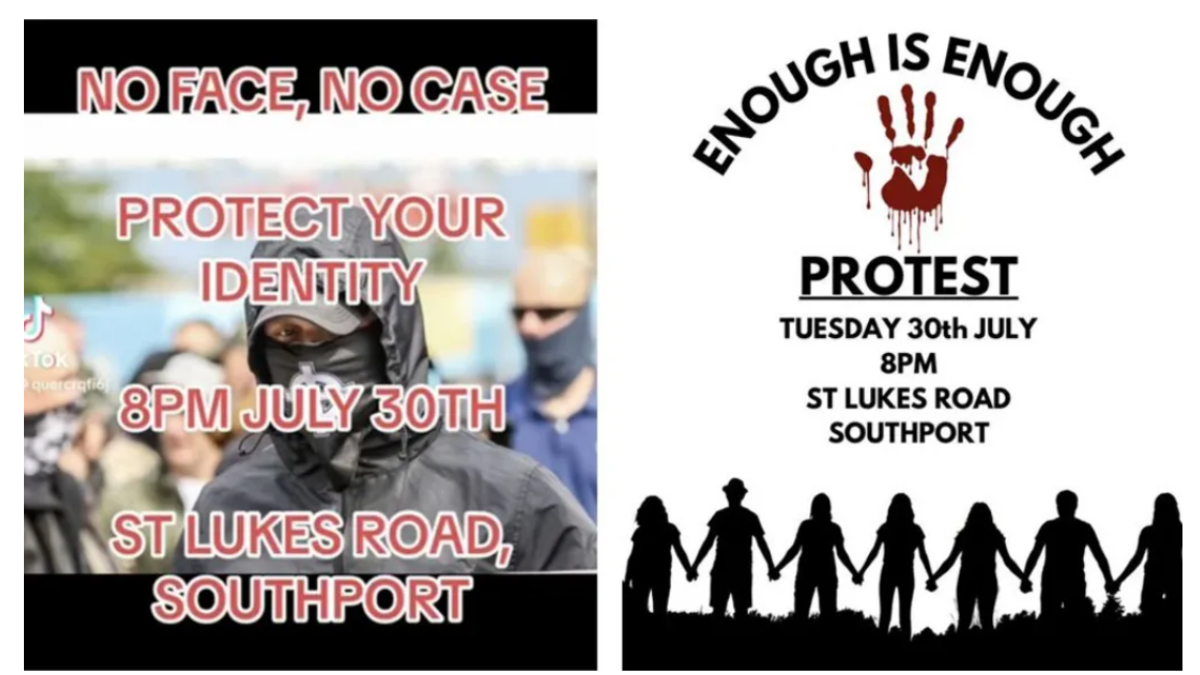

Images shared on social media identified by the BBC as promoting a riot near a mosque (source).

Ofcom’s Breton Moment?

Ofcom’s announcements bring to mind the comments of EU Commissioner Thierry Breton during riots in France last summer, when he backed remarks by President Macron to the effect that social media platforms could face shutdowns if they fail to remove illegal content during civil unrest. Ofcom is clearly less heavy-handed in its statements and also differed in its emphasis on processes rather than content: the DSA, while also for the most part regulating procedures, includes the provision for member nations to order platforms to remove specific instances of illegal content.

Nevertheless, Ofcom should be cognizant of the risks to civil liberties that can emerge when attempting to regulate, directly or indirectly, material relating to political protest. Breton’s comments prompted alarm in civil society, with 66 organizations signing on to a letter of concern. (Breton responded immediately with a more measured clarification. He has more recently drawn fire from free expression advocates and a rebuke from EU president Ursula von der Leyen for issuing an unauthorized letter to Elon Musk ahead of the billionaire’s interview with former President Donald Trump via X Spaces.)

Users, Not Platforms

The OSA also includes a number of offenses that individual users may commit. And, indeed, an August 16 review by the BBC of criminal charges relating to the riots identified 29 “online offences.” At least one person has already been jailed for a breach of the OSA’s online threats offense (which is actually a revision of an earlier “malicious communications” crime) due to her Facebook posts calling for a mosque to be blown up.

Many of the other charges appear to be instances of “stirring up racial hatred” by publishing and/or distributing the relevant content online. One man has even been sentenced to a jail term of three years for his posts on X that were deemed to meet the standards for this crime. This offense pre-existed the Online Safety Act, and does not specify that the material can be in electronic form or online. There have also been charges of “encouraging violent disorder” and “encouraging murder” brought (including against someone who allegedly advocated that the racist rioters be killed), again offenses that have no particularly notable online aspects.

The only charged offense I have been able to identify that seems more intrinsically “online” is the OSA’s “sending a false communication with intent to cause harm,” for which a Romanian TikTok user has been jailed for a post (later claimed to be a “joke”) in which he alleged that he was being pursued by anti-immigrant rioters—and even this law is a revision of an earlier offense.

Some statutes may need updating to apply to current technology, but these charges should demonstrate, as echoed by all of the police and prosecutor spokespeople in the official releases linked above, that traditional laws and law enforcement are able to deal with those who incite civil unrest online and hopefully discourage similar acts by others in the future.

***

In the wake of the riots, one of Britain’s most senior Muslim politicians, Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London, described the OSA as “not fit for purpose” and called for a review to see how it could better protect the country against online misinformation-fueled hatred. This review was initially endorsed by Cabinet Office Minister Nick Thomas-Symonds. But the Prime Minister’s office later denied that the OSA was being revisited, while committing to look into the role of social media in the riots.

Politicians and regulators regularly feel they must “do something” when a new harm emerges on social media. But what exactly they, or the platforms, must do is rarely clear. Albeit with varying degrees of investment and commitment, the mainstream social media companies do attempt to keep their platforms safe, but the nature of adversarial practices and constantly evolving phenomena make this work very challenging. This summer’s riots emerged and petered out in around six days. That is a rather short timeline to identify the actors, behavior and content that are at issue and develop effective strategies to mitigate the threat. While decisions like reinstating previously banned agitators like Stephen Yaxley-Lennon are clearly unhelpful, static regulations are unlikely to be of much value in preventing future issues.

Ultimately, social movements, both positive and negative, will use the communications resources available to them, from the printing press to the smartphone. Each of those technologies may enable—and shape—the movements, but history suggests that even overwhelming authoritarian force can only temporarily impede them. This should give pause to those who are eager to place the bulk of blame or acclaim for a social movement with the medium through which they organize.

Authors