Burn Book: Reckoning With the Power of Big Tech

Heath Brown / Feb 27, 2024Heath Brown reviews Burn Book: A Tech Love Story, published today by Simon & Schuster.

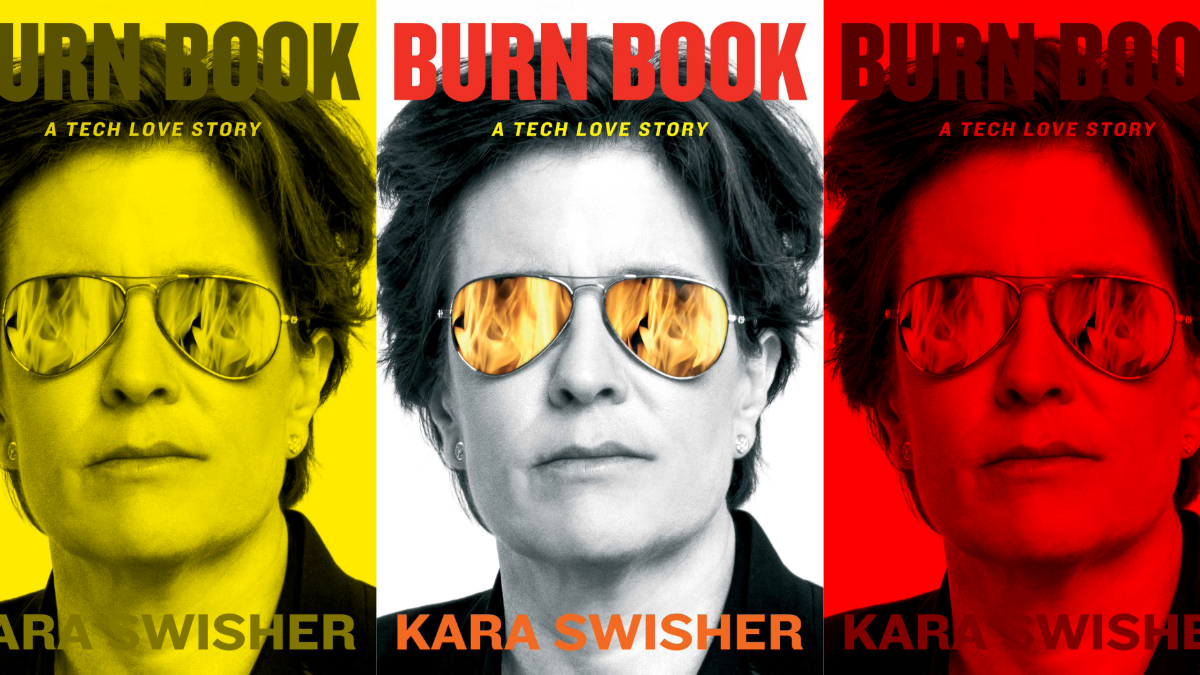

Burn Book: A Tech Love Story. Kara Swisher, Simon & Schuster, February 2024.

Kara Swisher starts her recently published love letter to tech in a most unusual time and place: not Menlo Park, Cupertino, or Seattle, but midtown Manhattan. Rather than a vignette from some Silicon Valley office park, Swisher recounts sneaking in the back door to Trump Tower for a face-to-face with the President-elect in early 2016. Donald Trump is Chekhov’s gun in Burn Book, looming in the background as we plummet through time from AOL to Yahoo to Google to Facebook.

In those early days after his election, Trump was scrambling to put together some semblance of a White House. Though he’d just unceremoniously fired the person in charge of helping him get ready— Governor Chris Christie—he’d made time in his schedule to accept the praise of the nation’s top Silicon Valley leaders, who gathered in a conference room for a photo opportunity.

In Burn Book, Swisher can’t believe they’d fall for this ruse, but warned them off Trump’s trap, nonetheless. She says she pleaded to anyone who would listen that Trump had no interest in their advice on his technology agenda, and that he only wanted to bask in their subservience and snap some photos to burnish his image.

To a person, the tech CEOs brushed off Swisher’s advice and headed in for the meeting, among them Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Elon Musk of Tesla, Tim Cook of Apple, and Sheryl Sandberg of Facebook, all filing onto the gleaming lobby elevator up to the 25th floor.

The meeting ultimately turned out as Swisher had predicted. The CEOs remained tightlipped about their disagreements with Trump on everything from immigration to climate change, while Trump got his clip on the evening news.

Nonetheless, in a brief video from the meeting, we did get a rare moment of candor from the President-to-be. Trump reassured the group once they sat: “You’ll call my people, you’ll call me. It makes no difference, we have no formal chain-of-command around here.” For once, he wasn’t lying: Trump’s White House was a leaker's dream, with many staffers taking Trump up on his promise that protocol would serve more like a ‘Facebook Suggested for You’ than an edict from the Commander-in-Chief.

Swisher made a career out of staying close to tech insiders who more or less employ Trump’s media strategy. “When it comes to scoops, you’d be surprised who’s leaking,” she writes. ”That’s because it’s nearly everyone.” Everyone from waiters to interns to CEOs are in on this game, and Swisher’s insights derive from the reality that this is how it all works.

As we move through the book, from the age of dial-up connections to high-speed Internet, Swisher grows despondent at the character of those high-placed leakers. Many in the early crowd, like Steve Jobs, Jim Barksdale, and Meg Whitman, are thoughtful and concerned about the humanity of tech. The later generation, like Elon Musk and Travis Kalanick, largely score high on her “Prick to Productivity” metric, more often than not childish, arrogant, and prickly. Swisher calls Zuckerburg “one of the most carelessly dangerous men in the history of technology,” and Facebook serves as the rickety bridge to the future that seems to worry her most.

Over time, Swisher shifts her focus from the tech nerds to the nerds in government, a full circle return to Washington, DC, where she’d started out as a student at Georgetown, and as an intern then cub reporter at the Washington Post. By January 6, 2021, Swisher was living on Capitol Hill and tracking Trump’s descent on Twitter. Chekhov’s gun fired that sad day. Following the violence at the Capitol, Trump was soon kicked off Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube; nothing more than a symbolic punishment for years of using those platforms to spread disinformation and undermine democracy unchecked.

This means when Joe Biden was sworn into office, Swisher was presumably still close by, yet the 46th president is barely mentioned in the book (Swisher proudly has omitted an index which could help confirm who’s in and who’s out. Biden shows up on page 158).

This is surprising, because four years after tech leaders amassed at Trump Tower, they’d gained a seat at the table for Biden’s transition. But unlike Trump’s invitation to kiss the ring and grab a photo, officials from AirBnB, Uber, and Lyft all volunteered to be on Biden’s actual transition team, as did others from Amazon and Google.

Leading them all was Jeff Zients, now the White House chief of staff, then just finishing a two-year stint as a member of the Facebook board. Zients left that board in March 2020 and sold his Facebook stock, just weeks before Biden began to organize his transition team. In the fall of 2020, Zients was heading up the COVID-19 Task Force, helping prepare for the transfer of control over the vaccine rollout.

He wasn’t alone. Former Facebook officials Jessica Hertz, Zaid Zaid, Austin Lin, and Erskine Bowles also held key positions on the Biden transition team.

On its face, it doesn’t seem like this would trouble Swisher. She’s not averse to anyone making a buck and lauds several policy makers for their understanding of tech, including Senators Mark Warner (D-VA), Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), and Michael Bennett (D-CO), as well as a few in the House, former Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI) and current Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO).

Nonetheless, the Biden transition (and ultimately his White House) differed from Trump’s in another important way: it didn’t leak. In completing research for a book due out this May, I contacted hundreds of members of that transition team. Most ignored my messages and many others politely passed on the chance to talk. For some, it was a nondisclosure agreement they’d signed with the Biden transition, binding for at least a year after the transition ended on January 20, 2021. For others, it was just the strict culture of that transition, firmly established after the disastrous leak of John Podesta’s emails in 2016.

Whatever the reason, just to be safe, the transition team sent everyone a secure laptop and all messages had to be sent through Signal, the encrypted app. A formal chain-of-command was widely understood and steadfastly abided.

I don’t know if Swisher’s contacts share as much today as they once did. It’s unlikely that NDAs reigned supreme in the ‘90s like they do today. It seems inevitable that the corporatism of tech and the move of its leaders into seats of political power will lead to less leaks from the sector, and thus fewer of the scoops that Swisher gathered up during the Wild West era of the Internet.

It’s likely good that the tech sector has grown up a bit, something Swisher would surely appreciate. But it also will probably result in less public insight into its machinations. Swisher’s given us that insider glimpse for 30 years, and our understanding of how this burgeoning sector operates has been the better for it. It’s not clear how the next 30 years will turn out; but at least the chance to hear Swisher call the next generation fools and idiots will make the burn feel good.

Authors