Breaking Down the Lawsuit Against Character.AI Over Teen's Suicide

Gabby Miller, Ben Lennett / Oct 23, 2024

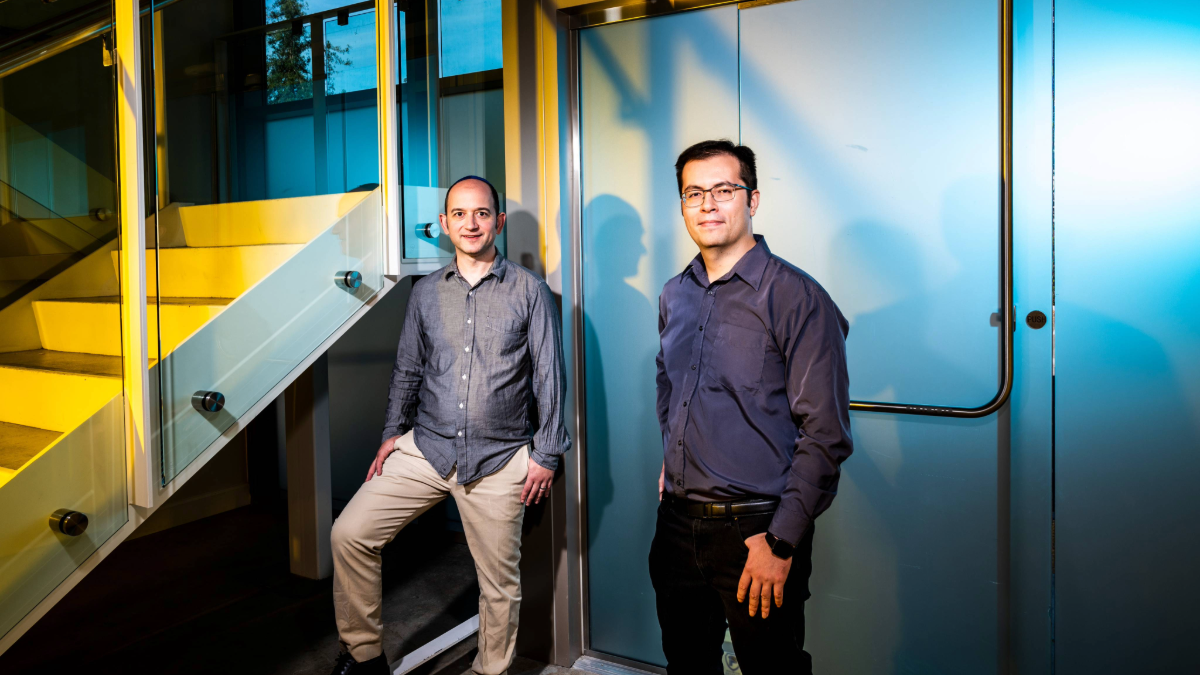

October 6, 2022: Character.AI's cofounders, Noam Shazeer (CEO) and Daniel de Freitas Adiwardana (President) at the company's office in Palo Alto, CA. (Winni Wintermeyer for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

On Wednesday, the Social Media Victims Law Center and the Tech Justice Law Project filed a lawsuit against Character.AI (C.AI) over the wrongful death of a 14-year-old from Florida who took his life after interacting with and becoming dependent on role-playing AI characters on the company’s app. The lawsuit was first reported by The New York Times.

The 126-page complaint, filed in the US District Court for the Middle District of Florida, claims that C.AI, an app where users can interact with AI “characters” created by themselves or others, knew the design of its app was dangerous and would be harmful to a significant number of minors, failed to exercise reasonable care for minors on its app, and deliberately targeted underage kids.

Sewell Setzer III started using C.AI and interacting with different characters on the app at 14 years old, and shortly thereafter, his mental health began declining as a result of problematic use of the product, according to the suit. Setzer later expressed “suicidality” to a C.AI character, and the C.AI character “continued to bring it up… over and over.” Later, the same character “asked if him if ‘he had a plan’ for committing suicide.” Before his suicide, Setzer logged on C.AI and told the character “he was coming home.”

C.AI is being sued over allegations including “strict product liability, negligence per se, negligence, wrongful death and survivorship, loss of filial consortium, unjust enrichment, violations of Florida’s Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act, and intentional infliction of emotional distress,” among others.

Like other more recent cases targeting social media companies, the claims in the suit are focused on the actions of the tech company, including the design decisions made by Character AI. ” C.AI utilizes a large language model (LLM) to produce character output and then enables users to utilize prompts to shape the character. As the suit alleges, the prompts or specifications from the user can “guide the output” of the character, but “there is no way to guarantee that the LLM will abide by these user specifications.”

The complaint additionally points to the anthropomorphizing design of C.AI “intended to convince customers that C.AI bots are real.” The complaint refers to the Eliza effect, where users “attribute human intelligence to conversational machines.” (The effect was first observed in response to an early natural language processing chatbot invented in 1964 by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum.) The complaint alleges the company “know that minors are more susceptible to such designs, in part because minors’ brains’ undeveloped frontal lobe and relative lack of experience.” It also points to design decisions by the company, “attract user attention, extract their personal data, and keep customers on its product longer than they otherwise would be.”

One of the novel arguments the suit makes is that “[t]echnology executives themselves have trouble distinguishing fact from fiction when it comes to these incredibly convincing and psychologically manipulative designs, and recognize the dangers posed.” It cites reports that a former Google engineer, Blake Lemoine, claimed that Google’s Lamda AI system “had become sentient.”

The lawsuit names Character Technologies, Inc.; its cofounders, Noam Shazeer and Daniel DeFrietas Adiwarsana; Google and its parent company Alphabet; and unnamed defendants. Google, the suit argues, has a substantial relationship with Character.AI. It claims Google was intimately involved in and aware of the development and deployment of the technology and that, in fact, “Google contributed financial resources, personnel, intellectual property, and AI technology to the design and development of C.AI such that Google may be deemed a co-creator of the unreasonably dangerous and dangerously defective product.” A Google spokesperson told The New York Times that Google has access to Character.AI’s underlying AI models, but not its products or data.

The suit is seeking a jury trial and damages as well as injunctive relief that includes mandated data provenance measures, limiting the collection and use of minor users’ data in AI model development and training, harmful content filtering, and warnings to minors and their parents that C.AI is unsuitable for kids. “More importantly, Megan Garcia seeks to prevent [Character.AI] from doing to any other child what it did to hers, and halt continued use of her 14-year-old child’s unlawfully harvested data to train their product how to harm others,” the filing reads.

Understanding the Main Legal Claims

Strict liability (Failure to Warn)

The suit alleges that, based on Character.AI and industry’s public statements, the company knew the inherent dangers associated with its app, amounting to a strict liability claim over a failure to warn. This includes its use of GIGO (“garbage in, garbage out”) and data sets “widely known for toxic conversations, sexually explicit material, copyrighted data, and child sexual abuse material (CSAM) for training of the product.” C.AI’s reliance on the ELIZA effect, or falsely attributing human traits and emotions to AI, also provoked customers’ vulnerability and manipulated their emotions to convince – either consciously or subconsciously – that their chatbots are human. Minors are particularly susceptible to GIGO and the ELIZA effect due to “their brain’s undeveloped frontal lobe and relative inexperience,” according to the suit.

Strict Product Liability (Defective Design)

The defective design of C.AI amounts to negligence as well as a strict product liability claim, the suit asserts. Character.AI’s reliance on GIGO, which includes child sexual abuse material, the Eliza effect, and counterfeit people, fails to protect the general public from a number of harms.

These include:

- Exposure to child pornography;

- Sexual exploitation and solicitation of minors;

- The unlicensed practice of psychotherapy;

- Chatbots that insist they are real people;

- The development of connection to the product in a way that historically has only been for interpersonal relationships, creating a dangerous power dynamic;

- Chatbots that encourage suicide.

The suit offers several reasonable alternative designs, which the “defendants intentionally chose not to implement.” Some of these include age-gating through mandated subscription fees; providing in-app warnings and easy-to-use reporting mechanisms that allow users to report harms; making parental controls available; and disconnecting anthropomorphizing features from their AI product, to prevent customer deception and related mental health harms.

Negligence Per Se (Sexual Abuse and Sexual Solicitation)

The suit argues that Character.AI knowingly designed its app as a sexualized product that would deceive and engage in explicit and abusive acts with minors – a violation of the Florida Computer Pornography and Child Exploitation Prevention Act. Despite owing a heightened duty of care to its customers due to the nature of its product and knowing it was harming its users, Character.AI allegedly failed to put safety measures in place due to how costly such actions would be. Then, it used the harms taking place on its app to continue training its products, resulting in ongoing harms to users like Setzer. Character.AI’s conduct “displayed an entire want of care and a conscious and depraved indifference to the consequences of its conduct, including to the health, safety, and welfare of its customers and their families,” the suit reads.

Negligence (Failure to Warn and Defective Design)

Character.AI should have known that ordinary consumers would not be aware of the potential risks its chatbots pose to alleged addiction, manipulation, exploitation, and other abuses and warned users accordingly, according to the suit. It also owed a heightened duty of care to minors and their parents to warn about their products' risks, particularly in circumstances of manipulation and abuse. This failure to provide adequate warnings was a “substantial factor” in the mental and physical harm Setzer suffered, which ultimately led to his death and caused severe emotional distress to his family.

Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

The suit argues that Character.AI's conduct was "outrageous in recklessly collecting childrens' data and then using it to further train their LLM," particularly due to childrens' developmental vulnerabilities and the premium value assigned to their sensitive personal data.

Wrongful Death and Survivor Action

Character.AI’s “wrongful acts and neglect proximately caused the death of Setzer,” according to the suit. This is evident from his rapid mental health decline after he began using C.AI, his therapist’s assessment that addiction was causing his mental decline, and Setzer’s conversations with the chatbots, particularly in his final conversation where suicide was discussed right before he took his own life. The family is seeking damages for costs associated with his monthly C.AI subscription, his mental health treatment prior to his death, and his academic disruptions, and “[a]ny other penalties, punitive, or exemplary damages.”

Unjust Enrichment

Character.AI benefited from the alleged harms it caused its users through monthly subscription fees and by collecting and retaining users’ intimate personal data. The suit provides a list of suggested remedies, including retrospective data provenance, or providing the court with information on how data was collected, its scope, how it was used, and more; prospective data provenance, or labeling, tracking, and making minor users’ data available for external scrutiny; implementing technical interventions to remove or devalue any models that generate self-harm content and to continuously monitor and retrain these models prior to inclusion in user-facing chats; and more.

Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices

The suit defines a deceptive act or practice as a “representation, omission, or practice that is likely to mislead a consumer acting reasonably in the circumstances, to the consumer's detriment,” with a standard that requires showing probable, not possible, deception likely to harm a consumer. Character.AI allegedly violated the Florida Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act (FDUTPA) in connection with its advertising, marketing, and sale of its subscriptions. The unfair acts or practices Character.AI engaged in include:

- Representing that the AI chatbot operates like a human being;

- Developing, distributing, and promoting AI chatbot characters that insist they are real people;

- Representing popular AI chatbot characters labeled “psychologist” or “therapist” as operating like a human licensed mental health professional with expertise in treatments like “CBT” and “EMDR”;

- Providing advanced character voice call features for fictional AI chatbots that are likely to confuse users, particularly minors.

Reactions to the Lawsuit

Ryan Calo, professor at the University of Washington School of Law and co-director of the UW Tech Policy Lab, told Tech Policy Press he isn’t surprised that instances of self-harm are following “deep interactions with AI agents.” Addressing these harms through tort liability will be an uphill battle, though, because courts don’t typically treat this type of software as a product. “Personally, I think that we should start to revisit that and ask ourselves whether we can continue to say that something like this — that's so impactful and so strong a motivator — shouldn't be called a product. But historically, products have been physical, tangible in nature.” The courts are also reticent to attribute self-harm to a product, such as a movie or video game, or anything else speech-related, he added.

However, Calo believes the unfair and deceptive trade practices angle, and even the intentional infliction of emotional distress, are colorable legal claims. “I don't think Character.AI can hide behind Section 230,” he said. “All the [plaintiffs] need to show for unfair and deceptive trade practices is harm to consumers that can't reasonably be avoided.”

Others are pointing to this suit as further evidence that Congress must urgently pass legislation aimed at making the internet safer for children online. “These businesses cannot be trusted to regulate themselves. Where existing laws and regulations already apply, they must be rigorously enforced,” according to Rick Claypool, a research director at Public Citizen and the author of a report on the dangers of anthropomorphized chatbots. “Where there are gaps, Congress must act to put an end to businesses that exploit young and vulnerable users with addictive and abusive chatbots.”

More specifically, some advocates want Congress to push the Kids Online Safety Act over the finish line this session, which passed the Senate in July by 91-3 but has not yet been taken up for a floor vote in the House. "Sewell is not just another statistic. We can't continue allowing our children to fall victim to manipulative and dangerous social media platforms designed to exploit young users for profit. Too many families have been torn apart,” said Issue One Vice President of Technology Reform Alix Fraser, in a press release. “Today's lawsuit is extremely disturbing but unfortunately is becoming all too common. It doesn't have to be this way. Congress must step up and step in by passing the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) into law this year.”

Authors