Beyond the ITU Victory: A Uniquely American Solution to Preserving a Global and Open Internet

Hiromitsu Higashi / Mar 2, 2023Hiromitsu Higashi is an MA candidate at Johns Hopkins SAIS and a Google Public Policy Fellow at the R Street Institute. His research focuses on internet governance. The views expressed in this essay do not reflect those of Google or R Street.

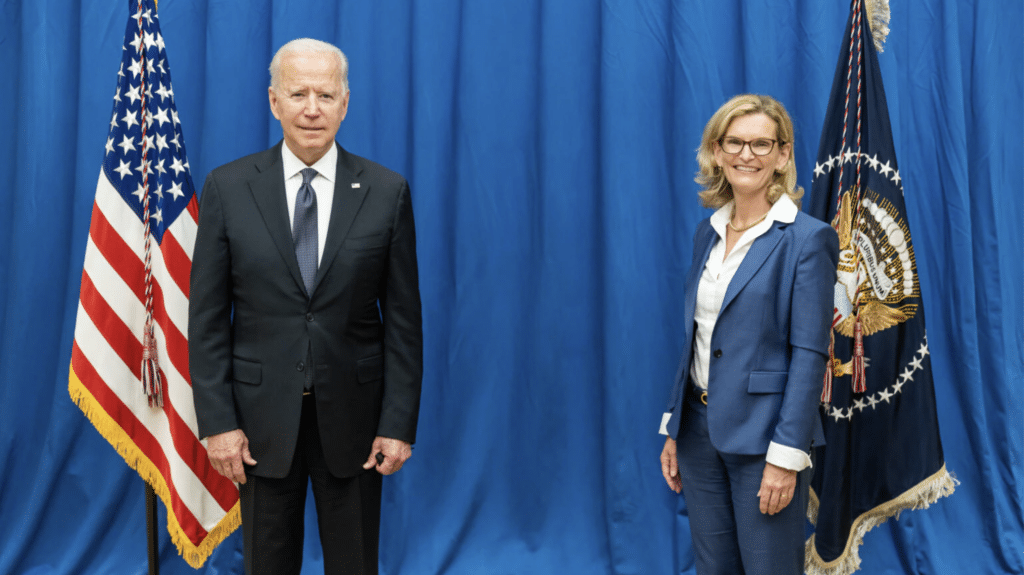

On September 29, 2022, Doreen Bogdan-Martin defeated her Russian competitor Rashid Ismailov in the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Secretary-General race. She is the first-ever female to head the 150-year-old organization, but equally consequential is her identity as an American candidate. In the fight against internet fragmentation – or “balkanization,” or “splinternet” – Ms. Bogdan-Martin’s victory must be of great relief for the U.S. government. Still, the preservation of a global and open internet will take more work from Washington than just ensuring the ITU is under ideologically friendly leadership. An effective solution would be market-based, bottom-up, and infused with individualistic ideals, namely the enhancement of U.S. innovative capacity and end-user empowerment.

ITU and the State of the Global Internet

A term with contested definitions, internet fragmentation may be best understood as the opposite of an open internet as defined by the Internet Society (ISOC): a network of networks (or, autonomous systems) underpinned by a set of “invariants,” such as global reach and integrity, interoperability, permissionless innovation, and universal accessibility. From data localization to censorship, practitioners have identified as many as 28 forms of fragmentation on technical, governmental, and commercial levels. There exists no consensus on the method to measure fragmentation, but there are several indicators to monitor. From 2017 to 2021, the number of data localization laws around the world has increased more than twofold, leaping from 67 restrictions in 35 countries to 144 in 62; global internet freedom has been on the decline for 12 consecutive years; and instances of government-imposed internet shutdowns exploded from just a handful in 2012 to over 210 across 33 countries in 2019.

But a global, open internet is consistent with the internet pioneers’ original vision as well as U.S. national interests. Its architecture reflects the values of free expression, market economy, and bottom-up governance. Reminiscent of U.S. zeal to promote democracy abroad, preserving an open internet has been a decades-long endeavor, spanning from investing in grass-roots internet freedom movements, countering authoritarian regimes’ influence in standard-setting organizations, and coalition building, to campaigning for a multistakeholder over a multilateral governance model, most famously exemplified by the ISOC/ICANN-ITU rivalry.

One of the Biden administration’s latest initiatives is its whole-of-a-government support for Ms. Bogdan-Martin’s ITU SG candidacy. For a decade, her predecessor, Zhao Houlin, has openly defended Chinese ICT companies, supported Beijing’s foreign policy initiatives, and attempted to expand the ITU’s scope beyond telecommunication issues, while Chinese companies flooded the standard working groups with proposals and pushed projects such as the “New IP” which might further fragment the internet by enabling more centralized, top-down control. In many ways, the ITU has always been an arena of geopolitical and ideological struggle, and Ms. Bogdan-Martin’s victory is no mean feat.

Lessons from the Internet’s Architecture

Nevertheless, preserving an open internet takes much more than the ITU being in good hands. Washington must be conscious of the three defining characteristics of today’s internet architecture: decentralization of governance, the multi-polar state of fragmentation, and voluntary buy-in to shared standards.

First, the existing multistakeholder governing model nullifies the dominance of any single entity. Originally a DoD-funded invention, the internet is now run by a plethora of entities, including civil society organizations, private companies, academics, governments, and international organizations, each with a direct say in the development, adoption, and promulgation of standards. The IANA stewardship transition in 2016 further solidified the model. As long as the current system endures, the influence of any single actor will be greatly limited, be it the U.S. government or the ITU.

The proximate explanation for this structure of internet governance lies in how the internet was created in the first place. The internet’s founding engineers, with a near-religious commitment to cyber-libertarianism, once firmly opposed any form of top-down governance. While the technical community eventually gave way to governments and, later, international organizations, the power struggle lingers and the culture of decentralized, bottom-up governance and technological freedom remains the decisive factor behind the internet’s success. Its anti-territorial nature continues to translate into a lack of synergy between place-bound political institutions and internet governance, exemplified by what some term a jurisdictional paradox. As such, to preserve a global and open internet, the private sector and individual users, not governments or international organizations, should lead the charge.

Second, the actual state of global internet fragmentation cannot be neatly categorized into an “open” versus “closed” binary per popular discourse. National networks, regardless of regime type, all possess meaningfully different or, sometimes, surprisingly similar profiles. Geopolitical allies may impose regulations antithetical to an open internet based on their own cost-benefit calculations, challenging underlying principles such as net neutrality and internet freedom. The complex reality cautions against any calls for coalition building with bright ideological lines, be it a “trusted, protected internet coalition” or “Digital Infrastructure and Defence Alliance.” Constructing Cold War-style digital blocks demands painstaking diplomatic investment and risks a misalignment between values and geopolitical interests – often at the expense of end users – not to mention the irony that such coalitions defeat the very purpose of a global, open internet.

Third, the adoption of internet standards is strictly voluntary. Akin to the voluntary connection of autonomous networks and exchange of data packets, governments, businesses, and individuals adopt the internet’s technical standards, from TCP/IP to HTTP, of their own volition. There exists no law, soft or hard, that prevents a country from, say, establishing its own DNS root from ICANN. Instead, it is the internet’s network effects that drive stakeholder cooperation and glue together a global internet. The sheer scale of today’s internet economy provides strong financial incentives for adopting interoperable standards and imposes tremendous opportunity costs on any attempted deviations from its current architecture.

An American Solution for a Global, Open Internet

As a result, in defense of a global and open internet, the United States must look beyond the ITU. American policy should seek to maximize the network effects of the existing internet architecture, resist the temptation to bring hollow geopolitics into the fold, and empower the key (and more effective) players in global internet governance, namely U.S. companies and individual users. There are two ways to achieve this.

First, the U.S. government should focus on enhancing American innovative capacity. Driven by geopolitical concerns, Washington has rightly made the renewal of technological competitiveness a strategic imperative. On top of that, Washington should further enhance the enabling environment for private capital flow into computer and information sciences, boost federal R&D investment while ensuring its complementary relationship with non-federal sources of funding, and, to the maximum extent possible, maintain a legal regime conducive to market competition, breakthrough innovation, and commercial scaling. In a multistakeholder model, U.S. tech firms with a competitive edge will possess a stronger voice in setting the internet’s rules and standards in international platforms and expand the network effects that remain a critical deterrence against internet fragmentation. All governments, democratic or not, must decide what kind of internet they want, and each and every U.S. technological breakthrough is a resounding affirmation of the net benefits of a global and open internet.

Of course, it would be naive to assume the expansion of tech firms always aligns with the interests of individual users. There are certainly circumstances in which state intervention, carefully tailored, can add value to addressing the gaps between private and public interest. Reflecting on the story of American technological success, however, the answer lies in the encouragement of risk-taking, self-regulation, and trial-and-error practices, with legislative intervention being the last resort. Take artificial intelligence (AI) as an example, the development of which often relies on the vast amount of data transmitted through a global and open internet to train algorithms. The Biden administration’s Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights educates the industry about the benefits of responsible AI development, enables federal agencies to lead by example, and strips itself of enforcement mechanisms to avoid a top-down “permission first” regulatory regime. It is a precedent to be followed.

Second, the U.S. government should incentivize the development of technologies that empower individual users. User empowerment means giving end-users a larger role in controlling their data flow (both domestically and internationally), what information they receive, and shaping their online environment in general at both technical and decision-making levels – a concept with extensive utility in encryption, financial services, data governance, content moderation, and AI adoption. Being able to make informed decisions levels the playing field for end-users against the concentration of power in private companies and top-down institutions such as governments, helps foster robust civil societies to participate in multistakeholder fora, contributes to stronger democratic institutions, and resonates with the internet’s original vision. The primary solution is to encourage the bottom-up development of such technologies through education, norm-building, regulatory sandboxes, financial incentives, agency workshops, and other forms of soft law.

On January 1, 2023, Ms. Bogdan-Martin was set to start her term as the ITU’s new SG. Whether the ITU will constitute a bulwark against internet fragmentation is yet to be known, but the line of inquiry should be directed to the role of the U.S. government in this struggle – Washington should lead, but by enabling the private sector and individual users to lead, through pro-innovation policy and end-user empowerment. After all, the metrics on which U.S. internet policy should be judged are whether it benefits the internet’s businesses and users, an open internet, liberty, and democracy more generally.

Authors