Assessing Parler’s Letter Documenting Warnings It Gave FBI of Jan. 6 Attack

Justin Hendrix / Jun 29, 2021One of the significant moments in the recent House Oversight and Reform Committee hearing on the Jan. 6 insurrection was the revelation that the social media platform Parler had sent several specific warnings to the FBI of potential violence in DC well in advance of the day. The letter that Parler provided the Committee laying out what it told the FBI is now a part of the January 6 Clearinghouse at Just Security. The letter’s details are significant. They deepen existing questions and raise new ones about the FBI’s intelligence failures before the attack.

Following multiple hearings at which FBI Director Christopher Wray has testified about what intelligence the Bureau acquired, analyzed, and shared in advance of January 6, it remains unclear why the FBI was so unprepared for the violence, particularly given the prevalence of social media posts across a variety of platforms that indicated the potential for such activity. The existence of specific warnings from Parler -- a site popular with former President Trump’s supporters -- was the first public confirmation that a social media platform had sent such specific notices to the FBI.

While Parler’s letter to the congressional committee has been referenced in news reports, the full content is remarkable for several reasons:

1) Parler took its response to the Committee’s request for voluntary production of information as an opportunity to address what it called “absurd conspiracy theories” about its platform. The 12-page letter it sent asserts that “Big Tech” engaged in “a coordinated and widespread disinformation campaign designed to scapegoat Parler for the riots at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, and to justify Big Tech’s unlawful and anticompetitive decision to de-platform Parler just when Parler was beginning to grow in size and strength, thereby presenting a viable threat to Big Tech’s stranglehold on social media.” Citing a poll that suggests many Americans believe tech platforms engage in politically biased censorship and a report that Amazon signed a contract to provide web hosting services to Twitter in proximity to Amazon’s decision to cancel hosting of Parler, Parler asserts the more prominent social media platforms and Amazon “colluded” to interrupt Parler’s growth, which it said threatened the hegemony of firms such as Facebook.

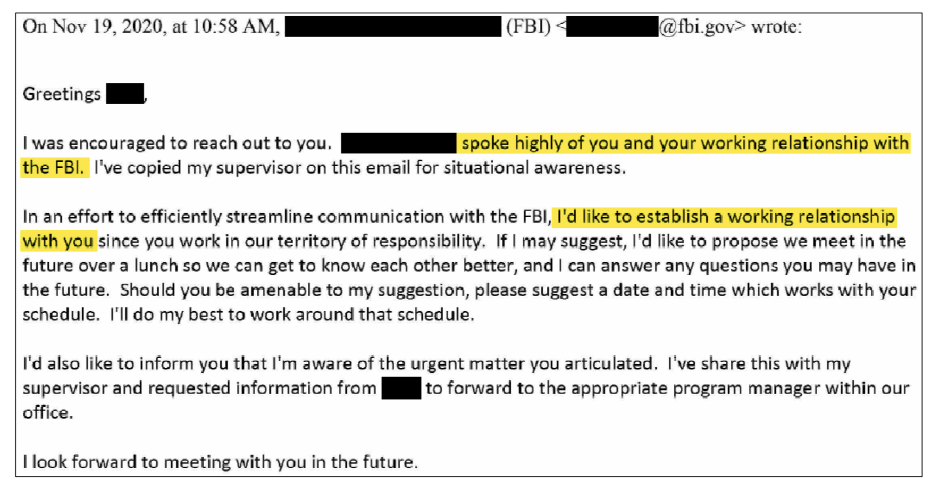

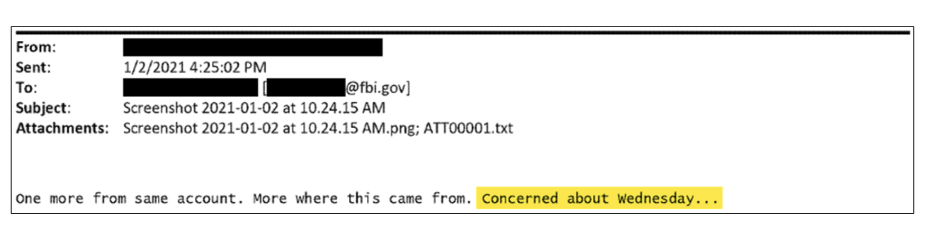

2) The company claims it was taking proactive steps to introduce moderation to its platform during its period of explosive growth following the November 2020 election, and that it “formalized” a relationship with the FBI at that time following outreach from an FBI agent. Parler includes a redacted copy of the email communication from the FBI agent, which references “an urgent matter” that the Parler representative “articulated” to the FBI that was shared with the agent’s supervisor and referred for additional attention.

3) Parler references a series of specific warnings it gave to the FBI about the January 6 events starting in December 2020. The company says, “on December 22, 2020, Parler sent the FBI three screenshots of particularly violent rhetoric from a user who threatened to kill politicians and who specifically threatened former Attorney General Bill Barr.” On December 24, the letter says, “Parler forwarded a post to the FBI from a user who called for the congregation of an armed force of 150,000 on the Virginia side of the Potomac River to ‘react to the congressional events of January 6th’” and that same day it “forwarded another unlawful post to the FBI in which a user stated that he was trying to ‘find some guys that are planning on lighting up Antifa in Wa[shington, D.C.] on the 6th’ because he wanted to ‘start eliminating people.’” Later, a Parler representative forwarded images of Hillary Clinton depicted in a noose and more specific concerns about January 6. According to Parler, “these referrals represent only a fraction of the dozens of posts with violent rhetoric that Parler collected and forwarded to the FBI for investigation in the days leading up to January 6.”

4) Parler goes on to make an argument that the amount of violent material related to the insurrection was more prevalent on Facebook and Twitter, while those companies faced no punitive consequences. The letter references the volume and frequency of Facebook posts and tweets related to the insurrection or by insurrectionists themselves, including those mentioned in public charging documents. And, it references, as bogus, claims made by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer, downplaying her company’s role in the insurrection. Sandberg’s statement has indeed been widely discredited.

The letter also takes on assertions about Parler’s ownership, refuting that it ever had any arrangements with Russians or that it offered Trump or his company an ownership stake. But, it offers a footnoted caveat that its former CEO may be in possession of information related to business dealings he conducted that the firm’s lawyers did not have access to in preparing their response to the House committee.

Some of Parler’s assertions are more arguable than others. Apple removed Parler in part for what it later referred to as substantial problems with respect to content moderation. Independent researchers at NYU who reviewed a substantial selection of 183 million Parler posts demonstrated the platform was a host to a large volume of scams, pornography and other problematic content. Analysts at the Stanford Internet Observatory separately reported that Parler had a variety of vulnerabilities, including a volume of inauthentic accounts potentially tied to foreign state actors and a potpourri of “spam, financial fraud and porn accounts.” The NYU researchers that studied the site’s contents even felt it necessary to “warn the readers that we post and analyze the dataset unfiltered; as such, some of the content might be toxic, racist, and hateful, and can overall be disturbing.” But it is true that Facebook, in particular, sought to deflect criticism following the January 6 insurrection -- Sandberg’s statements in February presaged Mark Zuckerberg’s practical denial of responsibility before Congress in March.

Another pressing national security concern is what the FBI did with the warnings it was sent by Parler. Before he appeared before the House Oversight Committee, Wray did not offer a specific answer as to whether the FBI received any tips from social media companies when he was previously pressed on the matter by Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-CA), at a House Judiciary Committee hearing earlier this month. At the House Oversight hearing, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) asked Wray about statements he made indicating he was aware of “online chatter” about the possibility of violence on January 6, and whether the issue was more of a failure to acquire intelligence or to a failure to act on intelligence the Bureau had. Wray referred to the problem of parsing the high volume of social media information -- separating the noise from the real threat -- a response he has offered multiple times in Congressional hearings.

But that response makes less sense in light of the fact that at least one platform sent specific intelligence related to the potential attack directly to the FBI through an established channel that the FBI sought to create. It raises the question: did Facebook, Twitter or YouTube send such warnings? How were these warnings passed onto others in the Bureau and other law enforcement agencies? Why was the FBI Director, according to his own testimony, unaware of these warnings before Jan. 6? Why does the FBI continue to assert it was unable to find any signal in the noise of an avalanche of social media posts, when it was presented with these highly specific, extraordinary warnings?

Perhaps these are questions that a Select Committee on January 6, expected to be established in the House as early as this week, may soon consider.

Authors