Another Internet Is Possible—If You Believe It Is

Victor Pickard, David Elliot Berman / Apr 20, 2023David Elliot Berman is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Media, Inequality and Change Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Victor Pickard is the C. Edwin Baker Professor of Media Policy and Political Economy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, where he co-directs the Media, Inequality & Change (MIC) Center.

The internet is facing multiple crises. From algorithmically fueled misinformation on Facebook to communities abandoned by large internet service providers, the tension between digital monopolies’ profit interests and the public interest is glaringly evident. Consensus is growing that the internet we have is not the internet that we want or need. In recent years, a diverse array of thinkers has begun to coalesce around bold ideas for radically democratizing the internet—from the pipes that connect us to the internet to the platforms that distribute news and information.

The Media, Inequality and Change Center recently brought together some of these scholars and activists to consider a key question: What does an internet for the people look like? Central to reimagining a more democratic and just digital world is an honest grappling with the limitations of a hyper-capitalist internet that is saturated by market logics, from targeted advertising to digital redlining. Such an appraisal should force us to ask: How can we take the internet out of the market? How can we decommodify, deprivatize, de-commercialize what has been thoroughly naturalized as a commercial space? And can we envision a truly public internet, dedicated to serving people’s needs in a multiracial democracy—not the profit imperatives of a few corporate giants and tech oligarchs?

The Dominant Paradigm: The Tinkerers and Tweakers

We are all tech critics now. While the corporate leviathans of the digital age are the subject of widespread criticism, this criticism is often narrow and procedural, marked by a curious absence of political economic critique that interrogates structures of ownership and control. Our technological imaginary is hemmed in by a widespread deference to the property rights and business models of Silicon Valley and telecom corporations. Reform efforts in the United States have generally sought to dither at the edges of Comcast and Facebook’s vast commercial empires.

The dominant paradigm of internet criticism is premised on the proposition that while the profit interests of corporations and the public’s interest are not always aligned, they can be reconciled through enlightened, discerning public policy. Adherents of the dominant paradigm seek not to slay the digital giants, but to tame their worst impulses. An algorithmic tweak here, a touch of competition policy there. Perhaps if Twitter or Facebook had a more enlightened billionaire at the helm, all would be right in Silicon Valley.

What the dominant paradigm of tech criticism ultimately suggests is that we can reform the internet from within the coordinates of our current profit-driven internet system—that we can tinker and tweak our way out of the structural crises plaguing our information and communication systems. This brutal state of affairs is presented not only as redeemable, but also as inevitable. As James Muldoon, channeling Fredric Jameson’s famous aphorism about our inability to contemplate alternatives to capitalism, laments: “It has become easier for us to imagine humans living forever in colonies on Mars than exercising meaningful democratic control over digital platforms.”

The Democratizers: Building a New Internet in the Shell of the Old

One of our aims at the MIC Center in organizing the Democratizing the Internet symposium was to bring together visionaries whose critique runs deeper and whose political imaginary for the internet’s future is more expansive than the tinkerers. This cohort of thinkers relate the manifold maladies that plague the contemporary internet to its underlying political economy. In this view, there is a structural antagonism between the owners of the internet and its users, between the profit interests of digital monopolists and the public’s interest in an open, empowering internet. In other words: we can have an internet that works for Silicon Valley and telecom companies, or we can have an internet that works for the people. But we cannot have both.

The failure of the digital goliaths to serve any semblance of democracy has inspired numerous attempts to create a more democratic, egalitarian internet. To underscore one concrete example of this alternative system: over the last twenty years, cities and towns across the country have taken it upon themselves to build their own broadband networks. Today, more than nine hundred communities in the United States offer high-speed internet access to their residents. In general, these networks are cheaper, faster, and operate more democratically than the networks owned by Comcast, Verizon, and other corporate internet service providers. For instance, Chattanooga, Tennessee launched its own fiber-optic network in 2010, and now offers a one gigabit-per-second connection to 180,000 homes and businesses in its service area. Rather than siphon off profits to executives or large institutional investors on Wall Street, the surplus generated by Chattanooga’s broadband network is used to subsidize free high-speed internet for low-income residents.

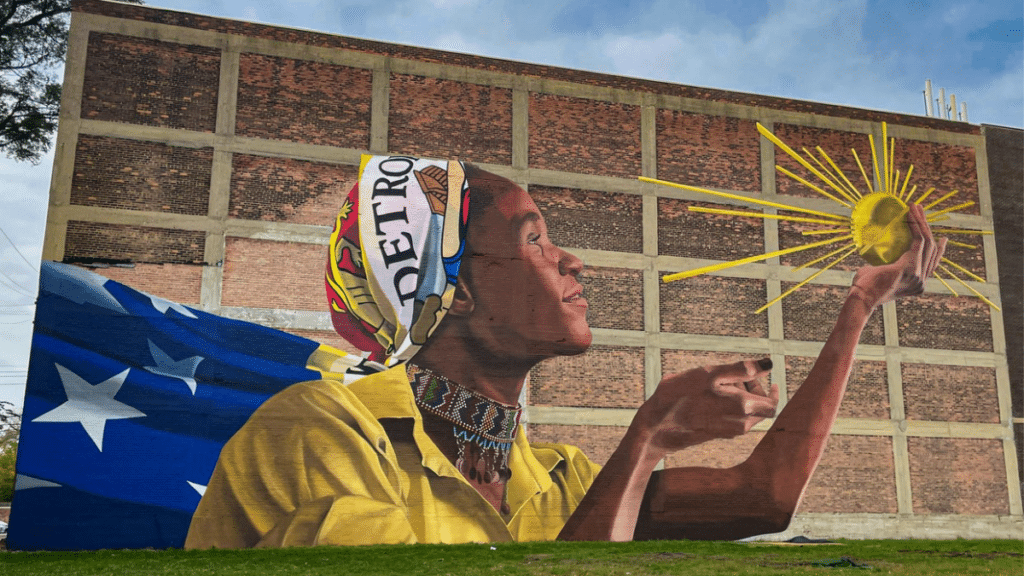

Public broadband thus prefigures what an alternative communications system—one committed to maximizing the public good rather than corporate profits—might look like. It gives lie to the conceit that the internet can only be provided by for-profit telecom giants that perpetuate digital inequities based on exclusion and extraction. Municipal broadband networks—along with smaller-scale community broadband projects serving marginalized neighborhoods in places like North Philadelphia and Detroit—are examples of what Erik Olin Wright refers to as “real utopias,” which spring forth not out of idealistic fantasizing, but as practical attempts to create spaces and institutions free from domination. Another internet is therefore not only possible—its germinations are already here.

Higher up the tech stack, numerous efforts are underway to implement radically new ownership and governance models for social media platforms. Researchers at the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure argue for a transition away from mega-platforms like Facebook to a “pluriverse” characterized by a multitude of very small online platforms (or VSOPs) in which governance decisions are made by the communities that use them. Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider propose applying the cooperative tradition to social media to create a platform ecosystem free from surveillance and exploitation. Others, like James Muldoon and Ben Tarnoff, reject centralized state governance of platforms in favor of bottom-up workers’ control and user democracy. While the precise methods by which non-commercial platforms will be governed is not yet settled, there is broad agreement amongst these platform radicals that the dominant social media outlets of our time suffer from, above all else, a lack of democracy and public accountability.

Indeed, it’s safe to say that the internet is failing today. It’s failing democracy, and a significant part of the problem is the commercial ownership and control over the internet’s every layer. Democratizing the internet—taking it out of the market—requires focusing on multiple layers, from the underlying material infrastructure of the internet to the platforms that power our social media and our online searches.

We must understand how the hyper-commercialized internet developed to see how we can dismantle it and build on the democratic experiments already emerging. We must build out public internet networks such as municipal broadband to confront digital inequities. And we must continue experimenting with new social media models. Although municipal broadband and alternative social media platforms may currently be relatively small in scale, they gesture toward a much more expansive political program for democratizing the internet.

Conclusion

From Facebook’s surveillance advertising to Elon Musk’s chaotic reign over Twitter, the social media ecology that emerged in the 2010s is now crumbling. As their business models falter, the hegemony of tech oligarchs over the public imagination is also waning. The internet is therefore at a critical juncture.

Now is the moment—or should be the moment—for radical projects and even utopian visions that go beyond simply tweaking algorithms or implementing better platform moderation policies. As important as those things are, small-bore reforms will not deliver the democratic internet that we all need. To do that, we must ultimately assert greater public oversight, control, and—yes—ownership of the internet.

Authors