Anatomy of the Big Lie: Participatory Disinformation vs. Democracy

Justin Hendrix / May 13, 2021In the months ahead, observers can expect more studies and reports that describe the ways in which the information ecosystem, warped and manipulated by a demagogue, helped propagate and advance the false voter fraud claims that motivated the January 6th insurrection at the US Capitol. The election and its violent aftermath offer an opportunity to query the complex relationships between media, technology, political elites and the crowd, and how they came together to propagate the “Big Lie.”

The receipts are currently being tallied, but some early results are in. The availability of data sets including Parler and Twitter posts are a starting point. In addition to academic studies underway, the Facebook Oversight Board has recommended that Facebook undertake a thorough independent review of the role its platform played in the insurrection and the propagation of falsehoods about the 2020 election, which may produce other public results. And, more insight will emerge from the study of YouTube, which experts confirm served as an important library of conspiratorial content embraced and advanced by proponents of voter fraud conspiracies.

Some researchers are already beginning to put the pieces together. Luke Munn, a researcher at Western Sydney University, studied Parler posts to explore the “concept of preparatory media and to unpack its key roles in mobilizing participants, inciting them toward violent activity, and legitimizing their assaults as logical or even ethical.” Robert Pape, director of the University of Chicago Project on Security and Threats, has compiled data about the racial motivations of the insurrectionists. And in a talk last week at the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics (IDDP) at The George Washington University, University of Washington professor and researcher Kate Starbird previewed work on the notion of participatory disinformation that connects the behaviors of political elites, media figures, grassroots activists, and online audiences to the violence at the Capitol.

The notion of participatory disinformation is not new. As described by MIT lecturer Michael Trice in a chapter of the edited volume Rhet Ops: Rhetoric and Information Warfare, the concept arguably achieved its modern form during GamerGate, a harassment campaign that targeted women in the video game industry. Indeed, “tools for participatory disinformation have never been easier to access nor more viable in application,” wrote Trice. “Complex assemblages can generate, store, and spread alternative media vetted by nothing so much as a community’s need to believe in the worst of their ideological opponent.” This phenomenon is well demonstrated in the last year by the behaviors of former President Trump, his campaign and his supporters.

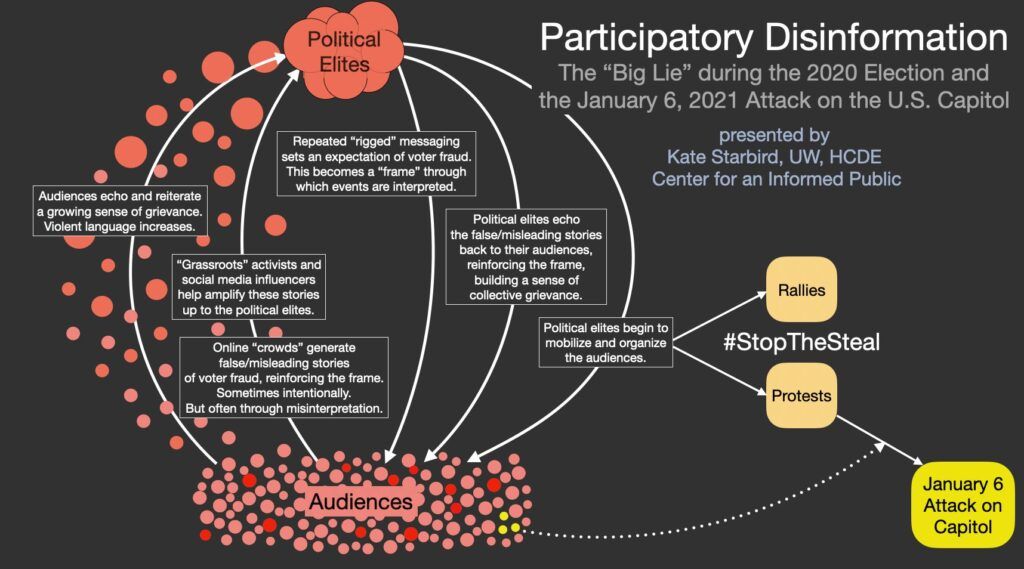

Starbird, who played a significant role in the Election Integrity Partnership, a coalition of university and private sector organizations that studied the information dynamics in the 2020 election, diagrammed the phenomenon in her talk at IDDP.

The diagram represents a starting point for discussing the various entities and forces- each in conversation with the other- that make up the broader participatory effort that is the Big Lie, and how it took advantage of social media affordances and dynamics.

Certainly, Trump was the primary driver of false voter fraud claims throughout 2020 and to this day, and his record of incitements is well documented. But as Starbird diagrams, he was hardly alone in the effort. Her diagram attempts to explain the nature of the relationship between elites- including “elected political leaders, political pundits and partisan media outlets, as well as social media influencers who have used disinformation and other tactics to gain reputation and grow large audiences online.”

Cornell researchers also identified key clusters in this group, including users that drove a great deal of the volume of voter fraud claims. For instance, individuals like former Trump campaign lawyer Sidney Powell, known for advancing a variety of spurious claims that- in legal jeopardy- she recently admitted were indeed false, was second only to Trump himself in terms of retweets during the period October 23rd and December 16th, 2020.

Lawmakers also participated actively. Representative Zoe Lofgren, D-CA19, compiled a nearly 2,000 page document detailing public social media posts from 102 Congressional Republicans between November 3rd, 2020 and January 31st, 2021. Her report is replete with false voter fraud claims, incendiary language, conspiracy theories, evidence of some Representatives’ associations with groups like the Proud Boys and Stop the Steal organizers, and in some rare cases images that glorify the siege on the Capitol.

The Trump campaign and the White House (often indistinguishable in the final days of the campaign and after the election) certainly saw the value in encouraging the collection of artifacts from across the country that, taken together, could be used to justify false voter fraud claims. Indeed, Axios reported that Trump’s “preparations were deliberate, strategic and deeply cynical. Trump wanted Americans to believe a falsehood that there were two elections — a legitimate election composed of in-person voting, and a separate, fraudulent election involving bogus mail-in ballots for Democrats.”

As Starbird notes, “with their perspective on the world shaped by this frame, the online ‘crowds’ generated false/misleading stories of voter fraud, echoing & reinforcing the frame.” Starbird notes that sometimes such stories were intentionally manufactured, but sometimes they were generated sincerely by individuals who misinterpreted things they observed or misunderstood facts.

But there is evidence the Trump campaign and the GOP encouraged this behavior. From at least March 2020, the campaign financed an effort to produce bottom-up evidence, which it called the “Army for Trump”. Reuters reported in October that Republicans were “mobilizing thousands of volunteers to watch early voting sites and ballot drop boxes leading up to November’s election, part of an effort to find evidence to back up President Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated complaints about widespread voter fraud.” By the final days of the campaign, the volunteers were in the field, armed with smartphones and trained to collect “evidence”. The Trump team and its supporters then stitched together the “evidence” into a national narrative.

In a late October appearance on MSNBC with Hallie Jackson, then White House National Press Secretary Hogan Gidley tipped his hand to the strategy. When Jackson disputed Gidley’s false claims of voter fraud, Gidley said “You can’t deny what you’ve seen on television in all of these local markets, where people are finding ballots in trash cans, people are finding ballots in ditches and in the back of trucks….” Jackson pushed back, citing the FBI Director's statement that there was no evidence of widespread voter fraud, to which Gidley replied, “Your local markets and all types of NBC affiliates are reporting on this in all types of areas across this country, this is rampant, everyone sees that.”

An example of one such claim was chronicled by the Election Integrity Partnership focuses on false information about discarded ballots in Sonoma County that started with a “report” from an individual. There are also countless examples of individuals across the country reporting perceived discrepancies and advancing conspiracy theories consistent with the claims of political elites. “There’s no end in sight to the conspiracies and misinformation,” a deputy commissioner in Philadelphia told The New York Times just before the election. “We’re being attacked for things that we have absolutely no control over.” The Times that in Philadelphia “Hundreds of people have called in every day for months, many parroting conspiracy theories about the election and lies about how partisan megadonors own the voting machines.”

The goal was apparent. “History will record that in the summer and fall of 2020, at the peak of the most unusual and bitterly contested election in modern times, the president and his team made a sport of plucking minor incidents from local news feeds and distorting them into data points of a grand conspiracy to deny him a second term,” wrote Tim Alberta in Politico just before the election, in a piece titled “A Journey Into the Heart of America’s Voting Paranoia.” “History will also record that their efforts have been wildly successful.”

Right wing media was a major reason for this success. An October 2020 report from Yochai Benkler and colleagues at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University found that Trump had “perfected the art of harnessing mass media to disseminate and at times reinforce his disinformation campaign” about the integrity of the election. Benkler and his colleagues warned that to thwart this disinformation operation, editors and journalists had to take special care not to “fall for the strategy the President has so skillfully used for the past six months.”

The report advised journalists to be more aggressive in explicitly identifying when the Trump’s assertions were false, reminding audiences that his stated strategy relied on these false claims, and not capitulating “to the inevitable charges of partisanship that will befall any journalists and editors who call the disinformation campaign by its name.” An unlikely example, perhaps, of journalists delivering on these suggestions was provided on the same day Benkler and his colleagues published their report by Fox News Radio’s Jon Decker, who confronted White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany on Trump’s claims that ballots were found discarded in a river.

But for every example of such a confrontation in defense of the facts, there are thousands of examples of false claims being propagated on right wing media. A much cited defense of one of the Capitol rioters, Anthony Antonio, is that he developed “Foxitis” or “Foxmania,” believing lies about the 2020 election he heard on Fox News. ProPublica reports that another rioter, currently imprisoned with other individuals charged for their actions at the Capitol, spent the post-election period “glued to Newsmax as it reported theories of how the vote was rigged” before planning to go to Washington DC on January 6th after Trump tweeted “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!”.

While the social platforms claim to have made unprecedented efforts to contend with the torrent of false claims related to the election, it is clear their remedies were not commensurate with the challenge. Anecdotal evidence abounds that the propagation of false claims on social media animated individuals primed to reject the results of the election.

And now, evidence is emerging that the platforms simply failed to see the big picture. BuzzFeed recently reported it had obtained an internal Facebook report that confirmed that far from succeeding in containing false voter fraud claims and the Stop the Steal movement that emerged after election, “Facebook failed to stop a highly influential movement from using its platform to delegitimize the election, encourage violence, and help incite the Capitol riot.” Echoing this conclusion, the Facebook Oversight Board, in its decision on the suspension of Trump’s account, said that “Facebook should undertake a comprehensive review of its potential contribution to the narrative of electoral fraud and the exacerbated tensions that culminated in the violence in the United States on January 6, 2021,” and that this review “should be an open reflection on the design and policy choices that Facebook has made that may enable its platform to be abused.”

It is possible such an inquiry could be part of the investigation conducted by a National Commission, given subpoena power by Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s proposal to establish the Commission includes a focus on social media- it says the remit of the Commission should include investigating “influencing factors that contributed to the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol and how technology, including online platforms,” and says that technology expertise must be included amongst the Commissioners. A vote on a Commission may come in the House of Representatives next week.

And, we should expect more studies to emerge related to disinformation and false claims in the 2020 election in the months ahead, including results from the 2020 Election Research Project, which seeks to provide “scientifically sound answers to critical questions” about the impact of Facebook and Instagram, in particular. A better understanding of participatory disinformation in the 2020 election and its aftermath may also help to inform how to contend with disinformation in a variety of other countries where social media has played a key role in extremism and violence, including in cases where governments leverage citizen support- such as Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines.

Even as our understanding improves, the dangers continue to metastasize. Of course, months after January 6 false claims about the election continue to propagate and inform beliefs of large numbers of Republicans. According to a recent Reuters/IPSOS poll, 60 percent of Republicans continue to believe the false claim made by Trump and his supporters that the 2020 election was stolen due to widespread election fraud. And the Washington Post reports a new set of GOP candidates are harnessing voter fraud claims to drive enthusiasm in their campaigns. "GOP hopefuls have a hard choice to make, whether to defend our country against pervasive disinformation that erodes democratic institutions (indeed, our very trust in the elections that define democratic governance), or jump in & benefit from these participatory disinfo dynamics,” wrote Starbird in a tweet.

But the participatory campaign is hardly over. Just this week, Republicans in the House removed Representative Liz Cheney from a leadership position for her repudiation of Trump’s false claims about the election. And in a House Oversight Committee hearing on the violence on January 6, multiple Republicans advanced blatant falsehoods about what happened that day. Arguably the only explanation that accounts for the coherence of this effort is that it is fundamentally motivated by white supremacy.

Given the scale of the effort now underway to manufacture and advance a false reality and to use it to disenfranchise voters, the only hope to make gains against it will be a collaboration of even more substantial scale and complexity. Researchers, government officials, responsible news media, and willing participants in civil society must come together to introduce a variety of remedies to interrupt the campaign, and extinguish the Big Lie. Understanding its anatomy points to potential points of leverage. There is much work to be done.

Authors