Analyzing Toxic Discourse on Latin American YouTube Channels

Cameron Ballard, Erik Van Zummeren, Alejandro Martin del Campo / Jun 26, 2023Erik Van Zummeren and Cameron Ballard are the founders of Raditube, a tool that helps journalists, rights advocates, and democracy defenders understand harmful content and actors on YouTube. Alejandro Martin del Campo is a Professor at Tecnologico de Monterrey.

In the beginning of June, YouTube announced it has reversed its policy on election misinformation pertaining to the 2020 presidential election in the United States. The company said it will “stop removing content that advances false claims that widespread fraud, errors, or glitches occurred in the 2020 and other past US Presidential elections,” since “while removing this content does curb some misinformation, it could also have the unintended effect of curtailing political speech without meaningfully reducing the risk of violence or other real-world harm.”

The move brought renewed attention to the problem of mis- and disinformation as well as extremism on the platform, and the link between the propagation of such content and real world harm. In an unpublished report, the investigative team for the House Select Committee that investigated the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol found that YouTube failed to take adequate steps to limit election misinformation between December 9th 2020, and January 6th, 2021. The site served as a key repository for false claims, which were “deployed across the rest of the internet.”

But no matter the scale of such problems in the US, various investigations into YouTube’s role in other regions has shown its shortcomings are more severe elsewhere, especially in non-English speaking countries. In Latin America, these problems are particularly acute.

For instance, in Mexico, 37 percent of internet users get their news through YouTube. The president of Mexico even broadcasts daily addresses on his official YouTube channel. Unfortunately, like other Spanish language content, we find that Latin American YouTube content is rife with channels that spread conspiracy theories and disinformation, including many channels that style themselves as independent news but function as fronts for illicit and/or political groups.

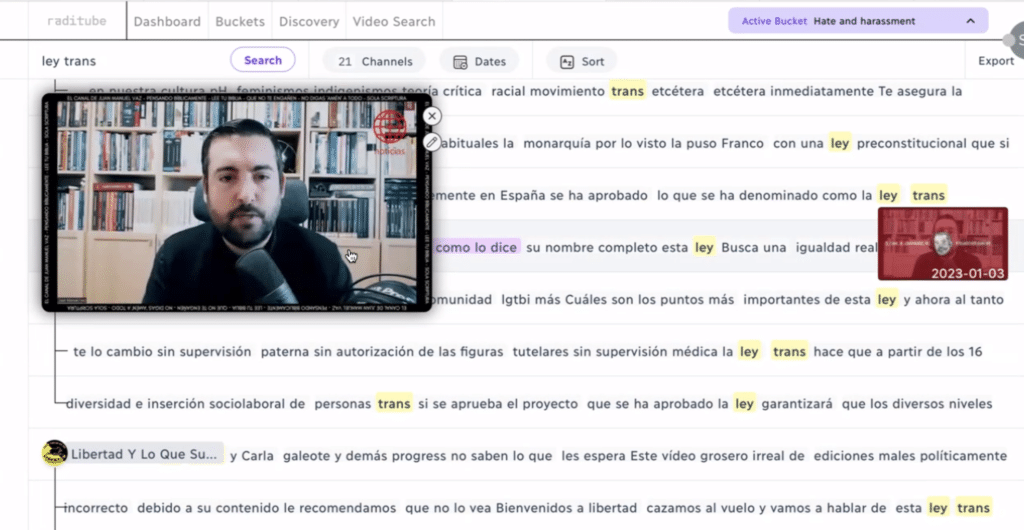

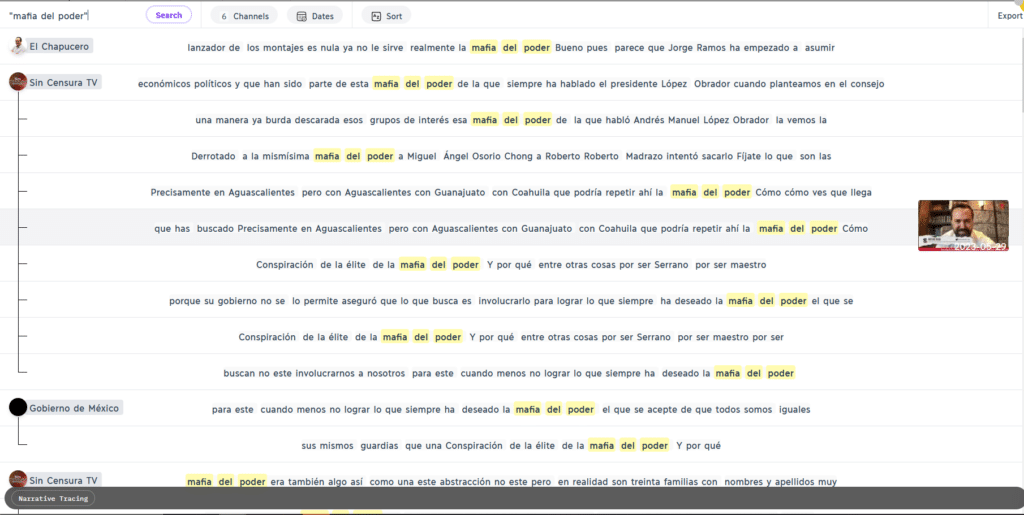

To facilitate and encourage research on the site, we developed Raditube, a research tool to make YouTube more accessible to journalists, academics, and other civil society researchers. Raditube helps users to easily find and track YouTube communities and quickly search through video content.

In February, we hosted a workshop at Tec de Monterrey with a group of about 25 participants (academics, researchers, journalists), most of them digital humanities scholars. Our goal was to familiarize the attendees with doing OSINT social media research, and introduce them to Raditube as a tool for researching YouTube. The participants first heard remarks from a number of individuals working to counter online disinformation on topics from the monetization of online disinformation, to OSINT research on violent extremism. Afterwards, the attendees split into groups to carry out their own projects using Raditube. Each group picked a current event prevalent in Latin American news and social media to examine its discussion on YouTube. We included some of the most interesting results below.

A predominant theme found across these groups was the alarming dismissal of violence against women and, indeed, femicide. Mexico faces a crisis concerning the disappearance of women and girls nationwide. Based on government statistics, 2,800 women were reported missing in 2021, igniting widespread indignation and demonstrations throughout the nation. A number of our research groups focused on YouTube content that perpetuates misogynistic representations of women or, to some extent, attributes the responsibility for these femicides to the victims themselves.

Some of this material is focused on drug cartels. A number of Mexican YouTube channels focus on covering incidents tied to the drug war in Mexico. These channels go by names like El Blog del Narco and El Mexa. Even though these channels initially emerged as an alternative source to conventional journalism that opted not to display the graphic images associated with the drug war, many now inadvertently contribute to the glorification of narco culture. On top of that, while the channels operate anonymously, there are indications that some of them may be controlled by cartel members. They often suddenly stop producing content, and appear again as a follow-up channel like El Blog Del Narco 2, possibly to avoid moderation, or simply due to a change in ownership. When covering the murder of women, they often blame the victim. For instance, one video we reviewed mentions that investigation of a murder by the authorities concluded that the murdered women were ‘responsible’ for their own fate. Another common theme is linking these victims to their work as sex workers in order to dehumanize them and shift responsibility away from their killers.

Apart from the “cartel journalism” content, many other channels regularly produce anti-feminist content in comedic, journalistic, or even academic formats. Content analysis showed strategies that include distorting and misrepresenting mainstream feminist arguments, using cover words to deflect moderation, and hiding misogynistic narratives in apparently innocuous life-style content. Other channels included anti-feminist content in broader “culture-war” arguments, framing feminist, anti-racist, and gender-queer theory as ideological conflict. One group in particular found that terms like “oppression,” “progressivism,” “imposition,” and “family” were repeated frequently along with words related to sexual orientation and gender identity, such as “homosexual,” “transgender,” “women,” etc. These terms were embedded among narratives against feminism and “woke culture,” depicting them as evil conspiracies and violent movements.

Similar conspiracy theories to those popular in the US also appeared in President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s official channel, and other channels supporting him. The conspiracy theory focused research group found many ostensibly unrelated “news” channels on YouTube simply repeating the talking points President Obrador shared in his morning addresses. Often, each channel had a number of conspiracies or themes they would discuss from Obrador’s addresses, but not all channels discussed all topics. Specific narratives are thus further amplified among different audience groups that watch different channels, improving the impact and reach of Obrador’s conspiracies without overt messaging by the Mexican state.

The results of the workshop highlight important similarities and differences between narratives in the US and Latin America. Common themes appear in both contexts, such as a broader culture war, anti-progressivism, and a framing of political disagreement as ideological conflict. Much of the content included direct and indirect references to common patriarchal and white supremacist talking points, including one popular creator who named himself “Un Tio Blanco Hetero,” or “A Straight White Guy.” Focusing on broader ideological narratives shared across languages and cultures would allow moderation efforts to be applied in a number of different geographical regions.

On the other hand, content outside the US also poses unique challenges for moderation. Creators styling themselves as independent news channels repeat state messaging and lend credibility to problematic narratives. Blog-type content masquerading as established news was also found in pro-Narco blogs and channels normalizing femicide. Without regional expertise and knowledge of cultural context, it would be difficult for moderators to distinguish between official and unofficial sources.

In addition, much of the content crossed geographical borders and came from all Spanish speaking countries rather than just Mexico. The already significant problem of moderation outside of the US is complicated by the domain specific knowledge necessary to recognize content themes within and across geographical and linguistic borders. For a language like Spanish, the official language of 20 countries on four different continents with almost 500 million native speakers, comprehensive moderation is as difficult as it is necessary. Even though video content is harder to study and moderate, YouTube’s place as the second most visited website in the world should make it a top priority.

These differences in content types have inspired us to look further into the types of YouTube content that are unique to Mexico and Latin America as a whole. As part of a follow-up we’ll be working on a taxonomy system and dataset that further captures these characteristics of LatAm YouTube. If you are interested in collaborating on this, or just to use the tool, feel free to reach out via email.

Authors