AI Safety Institutes Crop Up Around the World: Helpful or Hype?

Sriya Sridhar / Oct 25, 2024

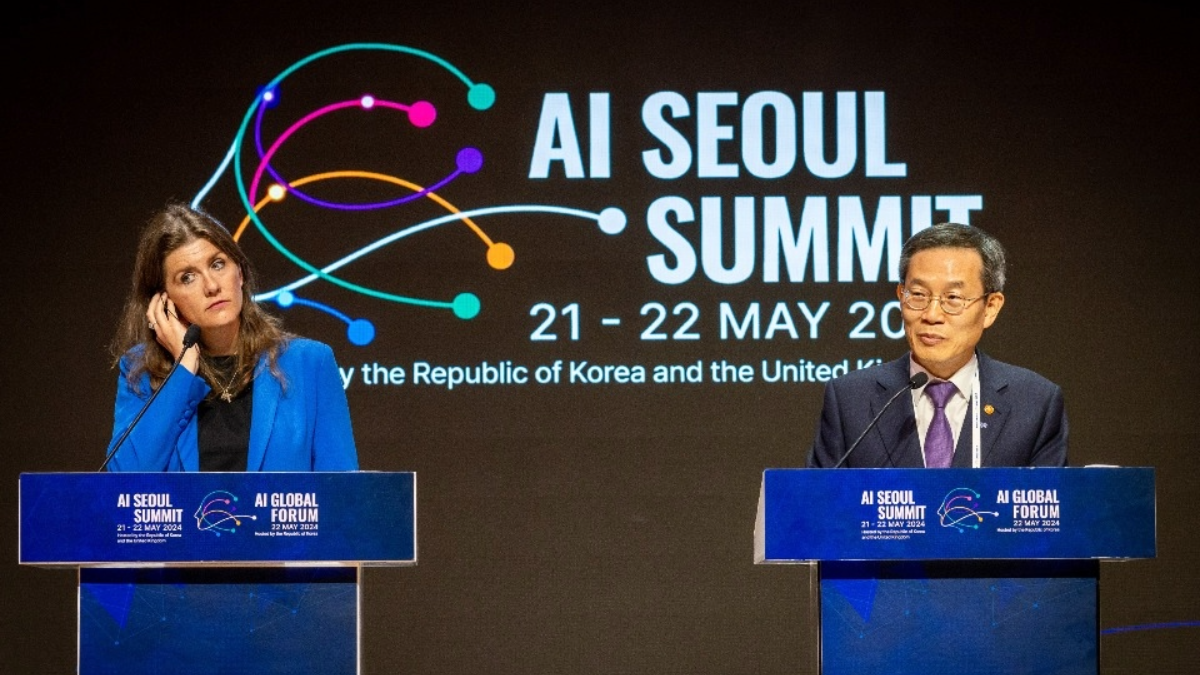

May 22, 2024, Seoul, South Korea: UK Technology Secretary Michelle Donelan, left; Minister Lee Jong-Ho of the Ministry of Science and ICT of the Republic of Korea, right. Source

Recent reports confirm that the Indian government is taking steps to set up an Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute (AISI) to develop standards, identify risks, and work towards developing AI-specific guidelines. The institute will also reportedly work on international coordination to share information on AI frameworks, and develop toolkits that the industry in India could use for evaluation.

AISIs are not new. Over the past year, multiple countries have set up AISIs. UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government set up its AISI in November 2023 under the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology. The US set up an AISI under the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), headed by a former economic adviser to the Biden administration. At the AI Seoul Summit in May 2024, an international network for AI safety was announced, which involved ten countries and the European Union. The aim of the network is to share knowledge on AI incidents and risks, among other objectives.

To be sure, AISIs have the potential for benefits. Given the rapid development of AI technologies and use cases, new forms of harm, the use of personal data to train AI models, and copyright issues, among other things, developing frameworks for safe and trustworthy AI is paramount. Sharing information to come up with workable security standards and guidelines, looking into issues of bias or discriminatory outcomes, and conducting research are all desirable goals to ensure sustainable innovation.

To comply or not to comply: it’s your choice

While AISIs hold promise, possible issues stem from the extent to which these models are centered around the adoption of voluntary standards and self-regulation. In India, too, the current proposal is for the AISI not to have any regulatory or enforcement power, but only for it to conduct research and develop suggested frameworks which the industry could choose to either comply with, or not. In essence, there is no intention for the AISI’s standards to be prescriptive in any way.

This is the approach in the USA and UK. The UK goes so far as to say that the AISI is ‘not a regulator, and will not determine government regulation.’ Similarly, in the US, since the AISI falls under the NIST, the adoption of standards for the private sector is voluntary. Japan’s AISI states similar objectives.

As far as India is concerned, this is consistent with previous statements from the Ministry for Electronics and Information Technology. The IT Minister previously said that ‘heavy’ regulation of AI is not the way to go for India, and that lighter regulation is more friendly to promoting innovation, in the same way that it structured data protection and telecom law. The Ministry’s secretary stated that AI regulations would ‘ideally be light touch, although harm is concerning.’ At the same time, the AI Advisory issued by the government earlier this year raised many questions about its exact scope and legality.

This is precisely the question that arises – how desirable is this push for self-regulation and voluntary adoption in AI when self-regulation has produced less than desirable outcomes in other areas?

The light-touch: A double-edged sword

The narrative of ‘light-touch regulation’ is common when it comes to any new form of technology, and in India, has been a consistent refrain when data protection legislation is discussed for telecom regulation, fintech, and digital competition. However, this approach has not led to the best results. Taking data protection as an example, the average cost of data breaches in India has only risen in recent years, with the exposure of users’ personal information occurring repeatedly. Despite these concerns, in its data protection legislation, India has provided the sweeping exemption for all public data to be excluded from the scope of ‘personal data’ and the protections afforded to personal data – which is good news for those looking to train models by web scraping public data but a net negative for privacy when regulators have raised privacy concerns arising out of these practices.

When it comes to AISIs, the light touch approach presents the same risks. It could promote innovation, encourage companies to adopt practices that increase trust in AI, and encourage international cooperation. However, when standards are not binding, and the institution has no regulatory power, this essentially does not lead to meaningful levels of scrutiny of risks and harms.

As compared to other sectors, AI has more disruptive potential, given its use in areas that have a large impact on our lives – such as healthcare, assessing creditworthiness, in workplaces, and for policing. In India, a survey conducted earlier this year revealed that around 50% of government and public service organizations want to launch generative AI solutions.

The push for an AISI to be the primary body for the foreseeable future determining the course of AI frameworks raises concerns regarding the ‘voluntary’ nature of their directives. In essence, this leads to the same result as self-regulation since companies deploying AI systems can decide whether these standards work for them. Ultimately, private companies are not accountable to the public, meaning their choosing to adopt certain standards bypasses democratic scrutiny. This pushes AI policy and regulation out of the domain of public, participatory processes by excluding relevant stakeholders and creates opacity around decision-making where the processes behind the decisions being made about people using AI need to be transparent, perhaps even more so than any other technology. This goes especially for India, where there have been concerns about the impact of AI on the democratic process itself.

Towards AI regulation with teeth

The AI Incident Database and inputs from experts demonstrate the issues with a self-regulation approach. While on the surface, these may be pro-innovation, they are likely to increase risk in the long term.

This is not to say that AISIs are a lost cause. AISIs can be constructive institutions to supplement regulatory agencies with enforcement power. For example, the European AI Office has broadly similar visions as the AISIs in the UK, US and India – with the key difference being that it has the power to act as a supplementary agency to enforce the EU AI Act. It can investigate infringements, set up advisory bodies for the implementation of the AI Act, implement delegated regulations, conduct reviews of AI models, request information and measures from model providers, and apply sanctions. In conjunction with these powers, it also aims to foster international cooperation, and develop guidelines, codes of conduct, tools, and benchmarks.

As compared to the UK’s approach, which developed ‘cross-sectoral principles’ for existing regulators to implement (without any new powers granted), the EU’s approach does not seem to make regulation subservient to innovation. The Biden administration’s Executive Order is also an example of balancing principles based on innovation with some concrete measures - although voluntary commitments remain a major AI policy plank. It is also worth noting that the FTC has been an incredibly proactive regulator in cracking down on AI related harms.

From the present information we have, India’s AISI seems to take a significantly ‘looser’ regulatory approach. In addition, the country doesn’t have any regulators who are simultaneously working on enforcement actions related to AI. The powers of regulatory bodies like the proposed Data Protection Board (which could have dealt with the intersection of AI and privacy) have also been significantly diluted in the present legislation when compared to previous drafts. Therefore, India’s AISI seems like it will be the only guiding body for a while. However, for human-centered AI, the development of which is rooted in accountability, transparency, and security, we need resources and budgets to be allocated to regulation with real power.

Authors