AI Regulation Versus AI Innovation: A Fake Dichotomy

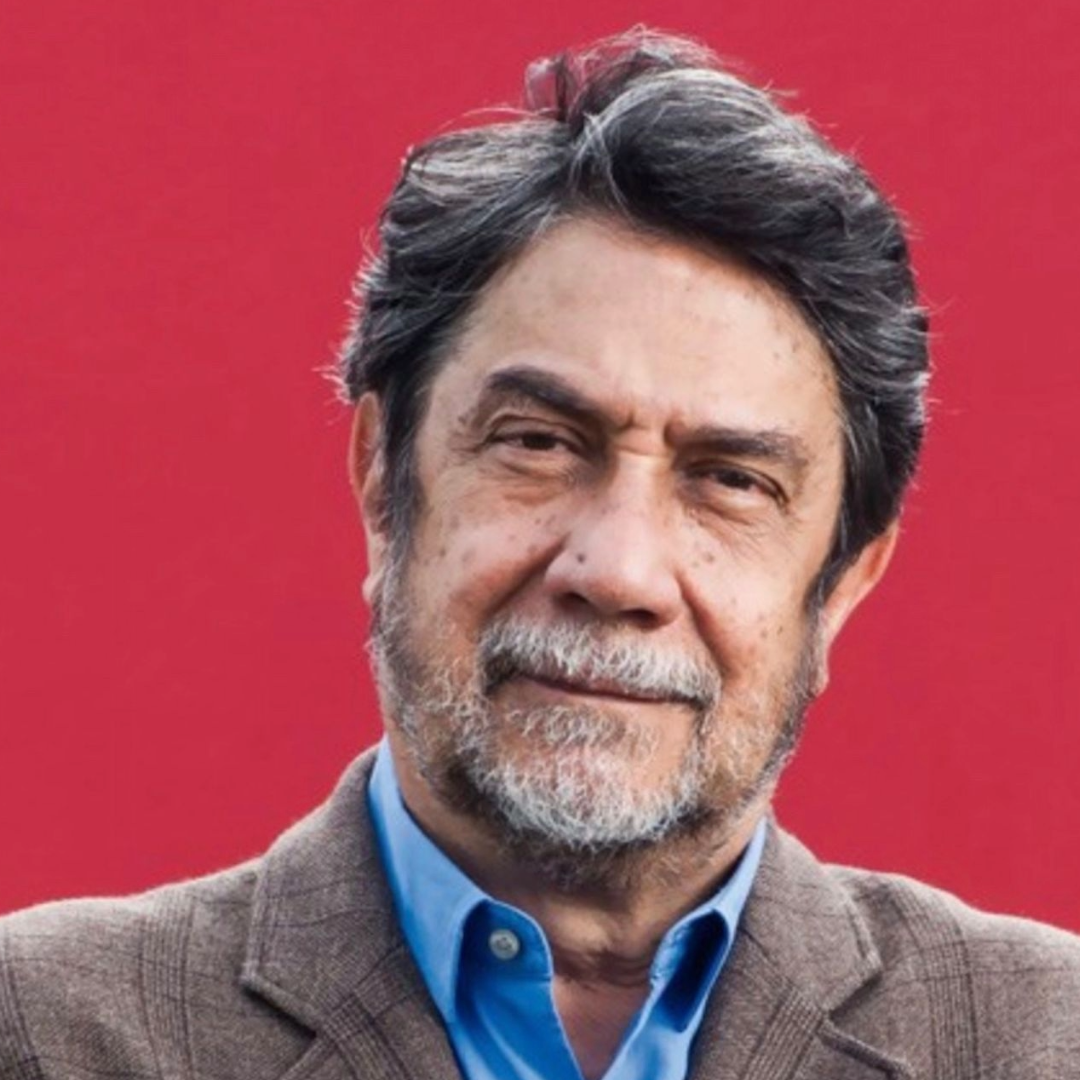

Fernando Filgueiras, Ricardo Fabrino Mendonça, Virgílio Almeida / Apr 18, 2025This post is part of a series of contributor perspectives and analyses called "The Coming Age of Tech Trillionaires and the Challenge to Democracy." Learn more about the call for contributions here, and read other pieces in the series as they are published here.

Is This Even Real II by Elise Racine / Better Images of AI / CC by 4.

The alliance between Big Tech and the new US presidency aims to limit the influence of digital regulations from Europe and other countries, imposing terms preferred by companies such as Meta, Google, and Amazon while resisting oversight by regulators abroad. The US government reinforces the interests of the companies by advocating for an AI policy focused on growth and deregulation, arguing that excessive regulations could hinder AI development and jeopardize the country's global leadership in the sector. These shifts are unfolding amid intense geopolitical instability, where domestic and foreign actors weaponize information and amplify its impact through data exploitation and AI-driven technologies, shaping a new global digital order.

At the core of AI technologies lie powerful algorithms and vast amounts of training data, which power applications widely used by governments and individuals worldwide. While AI has the potential to drive inclusive public policies and serve as a force for good, it also risks exacerbating wealth concentration to unprecedented levels if a corporate cartel consolidates control over its dissemination.

A key concern is AI’s impact on democracy, as it can intensify issues such as privacy violations, market volatility, and disinformation. Even before AI, social media was already teeming with hate and falsehoods spread through algorithmic systems. AI further accelerates and amplifies these processes, heightening the potential for manipulation of election campaigns and political discourse—both of which are heavily influenced by the financial and technological power of various interest groups. This technological power raises a crucial question: how can nations with different political and social realities and varying levels of development protect their values in a digital space dominated by tech firms? Moreover, how can democracies survive such a concentration of power in the hands of a few individuals who control such a vast amount of resources?

This new global power dynamic also brings moments of uncertainty—what can be seen as critical junctures, where significant change becomes possible, and key actors may play a decisive role in shaping institutional transformation. Examining institutional theories from political science and economics can offer new insights into managing international disputes over digital governance. In their research, 2024 Nobel Prize winners Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson highlight that certain historical moments — such as revolutions, wars, and economic crises — create opportunities for profound institutional change. These critical junctures can drive societies to transition from extractive to inclusive institutions, depending on how the benefits of change are distributed and who holds power at the time. The Nobel Prize they earned last year serves as a reminder of the critical role institutions play in economic and social development.

The new institutions

When Acemoglu and Robinson published the seminal Why Nations Fail, they made an important claim about economic development: the way society designs institutions and crystallizes them historically explains whether a nation will prosper or become poor. This economic finding was important in establishing the idea that a society can, for distinct reasons, choose between inclusive or extractive institutions. Inclusive institutions are those capable of producing greater transparency, equitable legal frameworks, and effective economic systems that produce long-term growth. On the other hand, extractive institutions are designed to keep political elites in power and prevent a democratic majority from participating in decision-making. Extractive institutions often produce systematic disorder, elite domination, and spasms of economic growth without comprehensive benefits to society.

This historical-economic corollary formulated by Acemoglu and Robinson can give us interesting clues about the process of change that is emerging in an increasingly digital world. The increasing datafication and digitization of society and the presence of disruptive digital technologies such as artificial intelligence produce a context of profound change in humanity. The transformations in the logic of work, government action, conflicts in war situations, cultural production, sociability, education, and information regimes, for example, transform the human experience globally, producing profound changes in the way we construct collective life.

In the current context of change, we are deinstitutionalizing various practices toward a new world of pervasive and ubiquitous digital technologies. If, on the one hand, we are deconstructing the institutions that undergirded the world order over the last few decades, on the other hand, we are rebuilding a new set of institutional ties through digital techniques and instruments.

At the core of these transformations, algorithms are reshaping human knowledge and redefining societal practices. Serving as the "rulebook" for computerized systems designed to fulfill specific objectives, algorithms play a pivotal role in the re-institutionalization and organization of society. It is no coincidence that digital transformation is presented as a new driving force behind upcoming change projects in various areas of society. Today, we speak of digital governments, digital societies, digital culture, and the digital economy. In this digital world, algorithms are central in constructing various systems that give shape and content to the human experience. We increasingly interact through machines or with machines to achieve various human goals. Within this process, algorithms structure the way our choices are formulated and our interactions take shape.

One rarely discussed aspect of this moment of profound social change is that we now face a collective choice with enormous historical impact. We have the choice between algorithms that can replace inclusive institutions or algorithms that reflect a process of extractive institutionalization. The problem, in this context, is central to the political economy of digital transformation.

The current scenario reveals that contemporary economic conflicts are centered on a dispute over technological dominance, particularly over digital infrastructure related to computing power and its impacts on society. The technology barons have understood that this emerging digital world is an open space for political dispute and that this scenario will be decisive for humanity. Control of technology implies structuring power in ways that modify the deepest foundations of capitalism. Without reducing algorithmic systems to mere operationalizations of individual intentions, it is important to acknowledge that some billionaires today hold enormous power over these technologies, which have been shaping interactional contexts and structuring power relations.

In this sense, thinking about how we will conduct digital development means the social dilemma of how to re-institutionalize the human experience along a path of extractive or inclusive algorithmic institutions. In the digital world, extractive algorithmic institutions, which may prioritize profit and data exploitation, use algorithms to extract income without benefiting society broadly. These organizations act like modern-day barons, controlling the infrastructure that supports technological advances. On the other hand, the possibility of inclusive algorithmic institutions means thinking about technological development in a way that benefits society by ensuring equal opportunities and redistribution in favor of the most vulnerable populations.

Democratic regulation as a key factor in digital development

This social dilemma that is currently emerging calls into question the false dichotomy between innovation and regulation in the digital world. Many technology corporations defend the idea that regulatory mechanisms harm innovation and, therefore, represent a major challenge to the need for technological advancement. The idea that regulation obstructs innovation and economic development is widespread in common sense. Moreover, many corporations and intellectual elites systematically argue against attempts to regulate digital technologies because any action in this direction would hinder their country’s ability to compete with others and, ultimately, retain sovereignty.

The problem is that institutionalization without or with poor regulation – and we see algorithms as institutions – tends to move in an extractive direction, undermining development. If development requires technological innovation, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson taught us that inclusive institutions that are transparent, equitable, and effective are needed. In a nutshell, long-term prosperity requires democracy and its key values. We must, therefore, democratize the institutions that play such a key role in shaping our contexts of interaction by affecting individual behaviors with collective implications. The only way to make algorithms more democratic is by regulating them, i.e., by creating rules that establish key values, procedures, and practices that ought to be respected if we, as members of political communities, are to have any control over our future.

Democratic regulation of algorithms demands forms of participation, revisability, protection of pluralism, struggle against exclusion, complex output accountability, and public debate, to mention a few elements. We must bring these institutions closer to democratic principles, as we have tried to do with other institutions. When we consider inclusive algorithmic institutions, the value of equality plays a crucial role—often overlapping with the principle of participation. Equality means, above all, that citizens must be included in decisions that directly impact their lives. Despite the political influence of tech elites, the specialized knowledge held by experts, and the vast resources controlled by big tech corporations, the societal impact of algorithmic institutions demands that the broader public has a voice. Society must participate in shaping and governing the global algorithmic infrastructure

Democracy is, hence, essential to safeguard prosperity and innovation by undermining the extractive tendencies of these new institutions and making them more inclusive. The fake dichotomy between innovation and regulation obstructs technological advancement and long-term development. This very same fake dichotomy is undermining our capacity to protect democracies in their current spiral of decay, which deinstitutionalizes our democratic institutions in the direction of authoritarian regimes.

Authors