A Step Forward for the Digital Markets Act, But Big Questions Remain

Max von Thun / Sep 14, 2023Max von Thun is the Director of Europe & Transatlantic Partnerships at the Open Markets Institute, based in Brussels.

Last week, the European Commission published its long-awaited list of tech giants and services designated as gatekeepers under the flagship Digital Markets Act (DMA). A response to the failures of traditional competition law to rein in Big Tech, the DMA – which entered into EU law last year – requires gatekeepers to comply with a wide range of obligations designed to prevent anti-competitive behavior and promote contestability in digital markets. The wide-ranging obligations for gatekeepers include enabling interoperability between competing messaging services, allowing end users to download third-party app stores, and refraining from self-preferencing one’s own services.

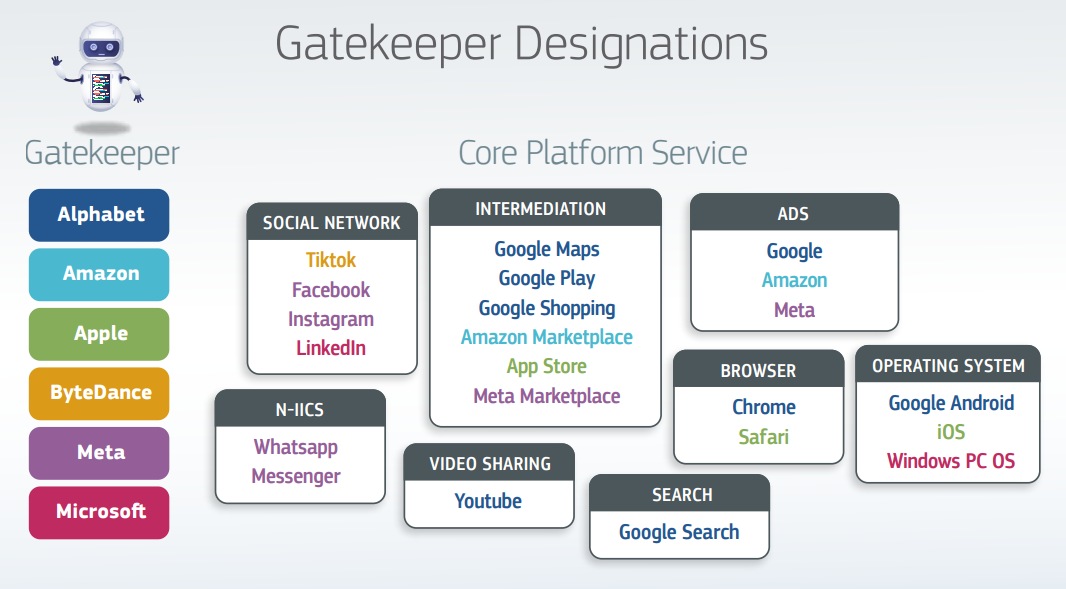

In total, six gatekeepers (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, TikTok owner Bytedance, Meta, and Microsoft) and 22 “core platform services” (a set of in-scope services defined exhaustively in the legislation) featured in the Commission’s gatekeeper list. As the Commission’s graphic below demonstrates, this list includes many of the usual suspects that have posed a problem for competition authorities, from Google Shopping (subject to the Commission’s very first investigation into the company back in 2010) and Apple’s App Store (notorious for extracting eye-watering fees from developers) to Amazon’s ubiquitous Marketplace and Meta’s dominant advertising business.

But the list also includes plenty of services that have so far escaped significant antitrust scrutiny, including LinkedIn, Google Maps, Safari, and Whatsapp. A service is considered a gatekeeper as long as it meets the DMA’s designation criteria (covering turnover, market valuation, user numbers, as well as other qualitative factors), regardless of its past track record.

The breadth of the designations and the Commission’s relative speed in making them is a welcomed development. Nonetheless, they also raise a number of significant questions. Most significantly, core platform services, including cloud computing (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud), email (Gmail, Outlook), and virtual assistants (Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant), failed to make the cut despite being used daily by millions of European residents and businesses.

Other noteworthy omissions include Microsoft Teams (currently subject to an EU antitrust investigation) and Apple’s MacOS operating system. The highly concentrated cloud computing market is arguably the most striking absence, given its critical role across both the private and public sectors – including its instrumentality in hosting generative AI models and apps. But the email services and virtual assistants supplied by Big Tech also act as essential hubs connecting people with businesses, while also giving them plenty of opportunities to steer users deeper into their all-encompassing proprietary ecosystems. Leaving gaps in the designations also risks incentivizing gatekeepers to concentrate their anti-competitive practices in those unregulated areas.

The Commission’s rationale for failing to designate these critical services is unclear. The press release announcing the decisions states that although Gmail and Outlook (as well as Samsung Internet Browser) met the thresholds for designation under the DMA, it opted to exempt them following “sufficiently justified arguments” submitted by the companies.

No explanation is given for the omission of cloud computing and virtual assistants. Insufficient user numbers may have something to do with it; under the DMA, a designated core platform service must have “more than 45 million monthly active end users established or located in the EU” and act as “an important gateway for business users to reach end users.” Yet, as a primarily business-to-business service rather than a business-to-consumer service, cloud computing may not meet the DMA’s end user and gateway requirements, suggesting the Commission will have to use other avenues to designate these hyperscalers.

The Commission is expected to publish the non-confidential details of its decisions in due course, which will shine further light on its reasoning – assuming the gatekeepers do not succeed in redacting any and all useful information. The Commission’s disclosures should include details on the arguments deployed by gatekeepers and potential gatekeepers so that civil society can scrutinize and, where necessary, challenge industry efforts to evade regulation. For similar reasons, the Commission should provide specifics on its rationale for both including and excluding specific companies and services.

Even at this early stage, it is clear that the Commission cannot simply exempt Big Tech’s cloud arms, email platforms, and virtual assistants without further investigation. Even if – as speculated above – the likes of AWS and Siri do not satisfy the DMA’s quantitative thresholds, the Act allows the Commission to conduct market investigations to determine whether a service that does not meet them should still be covered. Given the growing evidence of anti-competitive practices in both the cloud and internet of things, including numerous complaints received by the Commission, the case for doing so is strong.

As the first major step in implementing the DMA, getting the designation right will set the tone for the rest of the enforcement process. While the Commission undeniably faces significant resource constraints in its capacity to enforce the rules, unjustifiably exempting key areas of anti-competitive harm would undermine the DMA’s legitimacy from the get-go while providing no respite to those caught in Big Tech’s monopolistic dragnet. To give just one salient example, failing to impose obligations on the dominant cloud platforms would enable them to leverage that market power into generative AI – as is already happening.

As the first comprehensive effort anywhere in the world to use legislation to take on Big Tech’s monopolistic practices, the DMA’s success – or failure – in forcing the giants to overhaul their exploitative business models will send an important signal to other governments pursuing or considering similar reforms. The EU needs to get it right from the start.

Authors