A New Age of Trillionaire Philanthropy Is Coming. Democracies Should Be Wary.

Jeremy McKey / Jun 16, 2025This post is part of a series of contributor perspectives and analyses called "The Coming Age of Tech Trillionaires and the Challenge to Democracy." Learn more about the call for contributions here, and read other pieces in the series as they are published here.

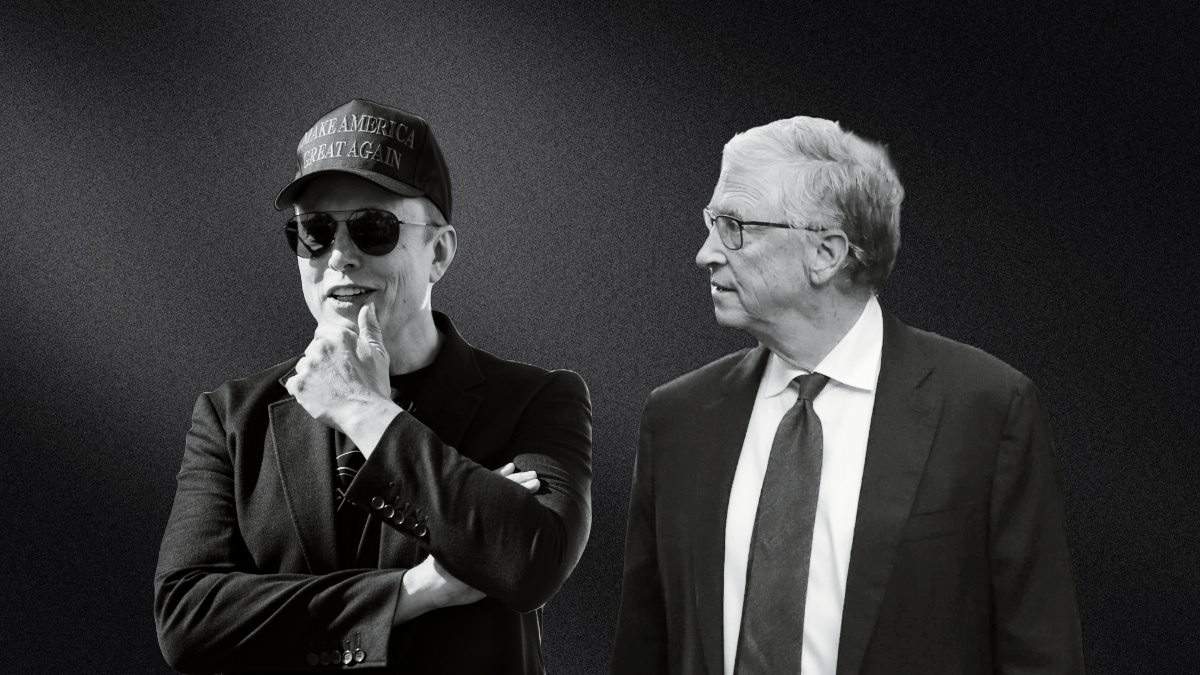

Tesla CEO Elon Musk and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates are depicted. (Wikimedia)

Bill Gates shook the philanthropic world last month with a surprise announcement: his namesake foundation would wind down by 2045, deploying $200 billion over the next two decades to “save and improve as many lives as possible.” His blog post, titled “The Last Chapter,” reflected on the arc of his personal life and legacy. But it also marked the closing of a larger era: the long century of billionaire philanthropy that sprouted out of the first Gilded Age, exemplified by Gates himself. In its place, a new philanthropic model is emerging among those poised to become the world’s first trillionaires.

Whereas billionaire philanthropy has historically been institutionalist — investing in American civil society and seeding a robust network of scientific and educational institutions — trillionaire philanthropy, when it emerges, may instead embrace an ethos of accelerationism: an ideology that countenances dismantling institutions seen to obstruct a techno-libertarian vision of progress. Democracy may become collateral damage.

The institutionalist legacy of billionaire philanthropy

The modern philanthropic foundation is a contradictory institution in the liberal democratic context. On the one hand, foundations are detached from voters and markets and often opaque, subject to only the most minimal reporting requirements. Shielded from taxation and permitted to exist in perpetuity, they often take on quasi-monarchical characteristics. According to scholar Rob Reich, foundations are “perhaps the most unaccountable, nontransparent, peculiar institutional form we have in a democratic society.”

And yet, as Reich goes onto argue, these undemocratic institutions can serve valuable democratic functions. One is the pluralistic provision of public goods — support for endeavors like avant-garde art or treatments for rare diseases that the state might be unable or unwilling to fund. Foundations can also provide risk capital, backing experimental efforts to address complex problems with long time horizons, such as climate change. Other scholars point to additional, contested roles that foundations might play, such as advancing intergenerational justice.

These tensions are not new. When John D. Rockefeller sought a congressional charter for his foundation in 1910, Reich documents, policymakers and civil leaders feared that the proposed institution — an unprecedented concentration of private power — would undermine democracy itself. Rebuffed at the federal level, the world’s first billionaire instead secured a charter from New York state for a foundation that would pioneer a new institutional architecture for giving at scale: professional in its operations, scientific in outlook, global in ambitions. The Rockefeller Foundation would go on to play a leading role in several of the 20th century’s most celebrated philanthropic achievements, including eradicating hookworm in the American South and launching the Green Revolution.

Another Gilded Age industrialist who helped define the long century of billionaire philanthropy was Andrew Carnegie, whose empire in steel rivaled Rockefeller’s in oil. If Rockefeller pioneered the institutional form of the modern foundation, Carnegie supplied its intellectual blueprint in his 1889 essay, “The Gospel of Wealth.” Written as he was building the vast network of public libraries across the United States for which he is justly celebrated today, the essay articulates an enlightened vision of private wealth accumulation. The unequal concentration of wealth, Carnegie argued, was an inevitable byproduct of capitalist technological progress. But with that wealth came a moral obligation: the rich must give it away during their lifetimes, rather than hoarding it, passing it to heirs, or even donating it posthumously. “The man who dies thus rich,” Carnegie famously wrote, “dies disgraced.”

Bill Gates, now 70, is determined not to die disgraced. Citing Carnegie’s essay as an inspiration, Gates’s post lays out a roadmap for giving away 99% of his wealth by the time he turns 90. That roadmap places Gates squarely within the philanthropic tradition blazed by Rockefeller, Carnegie, and other industrialists of the Gilded Age. It is a tradition that views the wealthy individual as a “trustee” for society’s wealth, in Carnegie’s formulation, with the bureaucratic foundation as the vehicle for administering the trust.

It is also a fundamentally optimistic tradition, another point of continuity between Gates and his philanthropic forebears. Carnegie opens “The Gospel of Wealth” by marveling at the technological progress of the modern era. Rockefeller saw his philanthropy as a way of spreading light around the world; oil itself was “the poor man’s light.” Gates, too, holds fast to a belief in progress, despite the current turbulence in the United States and globally. “You can accuse me of being by nature an optimistic person,” Gates reflected in a New York Times interview. “But I just think I’m being realistic. I think it’s objective to say to you that things will be better in the next 20 years.”

Then he adds: “In any case, let’s say somebody convinced me otherwise. What am I going to do? Just go buy a bunch of boats or something? Go gamble? This money should go back to society in the way that it has the best chance of causing something positive to happen.”

New ideologies for giving

One reason for Gates’s optimism — and his confidence in winding down his foundation decades ahead of schedule — is his belief that other wealthy individuals will take up the baton once he sets it down. “We are not running out of rich people,” he correctly notes in his Times interview. But a more sober view suggests that we may be running out of rich people whose vision of philanthropy bears any resemblance to Gates’s own.

To be clear, the foundation sector in the United States today remains alive and thriving. In 2021, over 100,000 private foundations across the country controlled over $1.2 trillion in assets, granting over $90 billion to everything from early-stage mRNA vaccine research to grassroots criminal justice reform. The sector grows year on year. Yet for those who sit at the very top of the world’s leaderboard of wealth, the foundation as a default mode of philanthropy is increasingly falling out of favor. Among the handful of foundations with assets exceeding $10 billion, most are anchored in the legacies of deceased donors — with Gates and business magnate Michael Bloomberg as notable exceptions.

The world of philanthropic data is notoriously opaque. It’s hard to say with confidence how much money, in absolute or relative terms, the top 100 wealthiest Americans are giving away. Many are still young, and may yet become major donors. Massive foundations may still emerge. But new trends complicate the picture: a growing number of the ultrawealthy are directing funds to donor-advised funds (DAFs), which confer immediate tax benefits without requiring annual disbursements of grants. Others, like Mark Zuckerberg, have bypassed the foundation model entirely in favor of LLCs, which offer more flexibility with even less transparency. Whether today’s tech elite are giving more or less, in relative terms, than the industrialists of a century ago is an empirical question muddied by shifting vehicles and norms. But there’s also a deeper question worth asking: Even if they gave more, would that be a good thing?

That normative question requires us to look beyond dollar amounts to the ideologies that animate elite giving today. One influential current is effective altruism (EA), a movement rooted in utilitarian philosophy and championed by figures like Peter Singer and William MacAskill. EA prioritizes maximizing the moral return on every dollar, often favoring causes like malaria prevention over traditional “civic philanthropy” focused on arts, education, or local institutions. While parts of the EA movement may indeed be “effective” and “altruistic,” its reputation suffered a blow following the collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto empire, given that Bankman-Fried had styled himself as an “earning to give” adherent and one of the movement’s most prominent funders. Still, EA remains a powerful framework among rationalist-leaning philanthropists in Silicon Valley, many of whom retain its core commitments to data, scalability, and a transnational moral calculus.

A more radical ideology shaping the philanthropic instincts of a new generation of tech elites is accelerationism. Introduced in the mid-20th century, accelerationism has gained traction in Silicon Valley circles in recent years as a loosely defined philosophical current that sees the intensification of technological and capitalist forces — not their containment — as the path to progress. One of the movement’s most provocative voices, the philosopher Nick Land, speaks of a “machinic desire” that steamrolls over institutions and traditions; the role of human agency is to facilitate its passage, embracing social and political crises as prelude to some sort of vague technological rebirth. By comparison, Ayn Rand seems positively sunny.

How might an adherent of accelerationism think about philanthropy? Even the phrase “accelerationist philanthropy” sounds oxymoronic — like a pyromaniac firefighter. Such a figure is unlikely to endow a public library (Carnegie) or fund anti-malarial bed nets (Gates). Nor is it easy to imagine such a person poring over grant applications or navigating the legal strictures of U.S. nonprofit law. The very idea of launching a foundation — an institution premised on the stewardship of private resources for the public good — seems ill at ease within accelerationism’s civilizational logic.

The anti-philanthropy philosophy of accelerationism is on full display in Marc Andreessen’s 2023 “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” — the closest parallel today’s techno-libertarians have to a modern “Gospel of Wealth.” But Andreessen’s gospel, unlike Carnegie’s, is dark: filled with “lies” to be refuted, “enemies” to be vanquished, and institutions to be torn down. His optimism is not hopeful but aggrieved. Drawing on thinkers like Nick Land, Andreessen frames technological progress as the highest moral good and casts the entrepreneur not as a steward of wealth, but as a civilizational savior. In this story, there is no room for philanthropy as a distinct life stage, no separate turn to charity in later life, no redemptive second act. Innovation itself is philanthropy. As Andreessen puts it, “Technological innovation in a market system is inherently philanthropic,” adding with a flourish of specificity — “by a 50:1 ratio.”

Satellites and submarines

Gates’s announcement that his foundation would accelerate its schedule to spend down came just weeks after Elon Musk fed USAID, the world’s largest development agency, “into the wood chipper.” The dismantling of USAID — an act projected by some to contribute to millions of preventable deaths in the coming years through lost vaccine access, nutrition programs, and maternal health support — brought to a boil the simmering feud between the two tech titans. “The picture of the world’s richest man killing the world’s poorest children is not a pretty one,” Gates remarked to the Financial Times. Not one to turn the other cheek, Musk fired back with a quip about Gates’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein: “I wouldn’t want that guy to babysit my kids.”

Their spat is more than personal; it marks an epochal shift in the perspective of the ultrawealthy toward the social purpose of their wealth. Gates stands at the end of a lineage of institutionalist philanthropy, grounded in the belief that private fortunes carry public obligations. Musk gestures toward something else entirely — a model of philanthropy that collapses the boundary between private profit and public interest. The era of billionaire philanthropy is coming to an end, and as the person most likely to cross the trillionaire threshold first, Musk, foreshadows a new dawn that looms over the horizon.

Though Musk signed the Giving Pledge in 2012, committing to give away a majority of his wealth during his lifetime or upon death, his philanthropic efforts to date have been spotty at best. One investigation found that the Musk Foundation, his primary philanthropic vehicle, fell short of the IRS-mandated payout requirement — 5% of a foundation endowment’s value — across multiple fiscal years. And what little it does fund often aligns with Musk’s private interests, such as a school for his own children and those of SpaceX employees. In a 2022 public disclosure, Musk — who has boasted about working 120 hours a week — reports dedicating a mere hour a week to foundation business.

The diminutive time allocation makes sense: Musk sees his foundation as a sideshow to the far more important philanthropic mission of his life: his companies. As Musk has repeatedly emphasized, his real philanthropic work lies not in making grants but in building businesses — especially SpaceX, the crown jewel of his empire. Founded in 2002, SpaceX has a singular mission: to make humanity multiplanetary by establishing a self-sustaining colony on Mars. “The sun is gradually expanding,” Musk explains, “so we do at some point need to be a multiplanetary civilization because earth will be incinerated.” This is a radical, long-term project that Musk is pursuing through his LLCs, rather than his foundation. After all, US nonprofit law does not offer clear guidance on grants to Mars.

But even in more terrestrial and immediate terms, Musk’s giving remains largely outside the boundaries of traditional philanthropy. Consider Musk’s (rebuffed) offer to build a “kid-sized” submarine to save the youth soccer team trapped in Thailand’s Tham Luang cave and, most recently, his provision of thousands of Starlink satellite terminals to Ukraine. A familiar pattern emerges: a high-profile crisis makes headlines, Musk offers a technological fix via X (née Twitter), and the gesture often conveniently boosts one of his companies. For Musk, traditional philanthropy is seemingly less about long-term strategy than public spectacle.

Does his philanthropy also endorse an ethos of accelerationism? It is hard to say. Musk’s ideology is a moving target, notoriously difficult to pin down. What is clear, however, is that accelerationists are firmly in Musk’s orbit. In addition to Marc Andreessen, a close advisor, this includes Peter Thiel — Musk’s PayPal cofounder and fellow South African — who has championed anti-democratic and techno-libertarian views. Whatever Musk thinks about accelerationists, moreover, they think highly of him. Curtis Yarvin, a leading accelerationist who advocates for replacing democracy with monarchy, initially celebrated Musk’s efforts at DOGE — before lambasting them for not going nearly far enough.

Trillionaires on the horizon

Billionaire philanthropy, a deeply flawed institution, has attracted no shortage of criticism. Whether operating domestically or abroad, billionaire foundations can be elitist, overbearing, and unaccountable. Even Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” —the founding charter of modern philanthropy — is steeped in paternalism, asserting that “the man of wealth” should act as the “agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer…” That logic, once celebrated, now reads as cringe-worthy.

But as the Gates Foundation prepares to spend down, it’s worth asking what might be lost when the era of billionaire philanthropy is past. Billionaire philanthropy helped build many of the educational institutions now under siege. Large foundations played a vital role in several of the twentieth-century public health victories — supporting access to the polio vaccine, for instance — that are now cast in doubt by the unraveling of public health consensus. At their best, foundations have shown a capacity for self-reflection about their own contradictions, taking steps to strengthen the democratic institutions currently being tested as never before in modern American history.

By contrast, trillionaire philanthropy is likely to be more opaque, more powerful, and more personalist than the philanthropic tradition it succeeds. Foundations offer tax advantages to the wealthy, but they also impose some guardrails — rules on payouts, limits on self-dealing, and a minimal degree of transparency. As a new generation of ultra-wealthy donors explore vehicles beyond foundations — encouraged, in part, by Trump-era attacks on the foundation sector — those guardrails may vanish entirely. The result could be a model of philanthropy untethered from philanthropic institutions and openly hostile to democracy. If billionaire philanthropy could be paternalistic, trillionaire philanthropy may prove messianic.

Philanthropy can reflect generosity, but beyond a certain level of wealth, it is not really a choice. Giving becomes a necessity. As Gates understands, there are only so many boats one can buy — or that one’s children, or children’s children, can. There’s only so much gambling to be done. Eventually, the question becomes how best to give what remains away. For Gates, that means returning money to society “in the way that it has the best chance of causing something positive to happen.”

By the time the Gates Foundation has spent down, the era of tech trillionaires will be well underway. What their philanthropy looks like — what they believe “something positive” means — is still an open question. But one thing seems certain: with trillionaire philanthropy, all bets are off.

Authors