A National Heist? Evaluating Elon Musk’s March Through Washington

Justin Hendrix / Feb 9, 2025Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

As Donald Trump’s second presidency enters its third week, Elon Musk is center stage as the Department of Government Efficiency moves to gut federal agencies. In this episode, Justin Hendrix speaks with two experts who are following these events closely and thinking about what they tell us about the relationship between technology and power:

- David Kaye, a professor of law at the University of California Irvine and formerly the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, and

- Yaël Eisenstat, director of policy impact at Cybersecurity for Democracy at New York University.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

David Kaye:

I'm David Kaye. I teach law at the University of California Irvine and I was for six years the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression.

Yaël Eisenstat:

I'm Yaël Eisenstat. I am the director of policy impact at Cybersecurity for Democracy. I'm based out of New York University.

Justin Hendrix:

We're going to have a free-ranging conversation, a "drawn from the headlines" conversation, and try to cover a lot of ground about what's going on in the United States and the implications elsewhere. David, I'm going to put you on the spot and start by maybe drawing you out on something I saw you share on social media a little earlier. You made reference to Tim Robbins' 1992 film Bob Roberts. If folks don't know that film, “Millionaire Conservative Bob Roberts launches an insurgent campaign against incumbent Senator Brickley Paiste (Gore Vidal) firing up crowds at his rallies by seeing 60s-style acoustic folk songs with lyrics espousing far-right conservative social and economic views.” That's the blurb on the film from Rotten Tomatoes. What about that film makes you feel like that's the moment we're in?

David Kaye:

Yeah, so Bob Roberts, it's a Tim Robbins movie from 1992. It's a great film, I think, for anybody who wants to see it. It might be a little bit too close to home at the moment, but the thing that really struck me about its prescience, particularly at this moment, was not only the use of a propaganda and trolling style of leadership but also Bob Roberts had around him these youthful zealots, these acolytes who seemed really just a bit nuts. One of them was played by Jack Black, so you could imagine an over-the-top Jack Black, I think it was his first film. But for me, the moment, one of the reasons I keep thinking about it is there's a frenzy of propaganda and disinformation but also energy around this particular person, and I think we see a lot of that right now, and we see that particularly in the context of Elon Musk bringing in these young guys. I think they're all guys who seem to have extremist backgrounds. The reporting is dribbling out. It's really excellent reporting on that, and it's that in particular that reminded me of Bob Roberts just over the last day.

Justin Hendrix:

So you said what we are seeing is a lawless criminal enterprise, a national heist, a global threat, a betrayal of the constitution, these are strong words. Is this what's happening?

David Kaye:

I think it is what's happening. I think there's a lot of opacity. There's no transparency around a lot of what we're seeing, and that's certainly the context of whatever this doge is, this department of governmental efficiency that was created by Trump by executive order and that evidently Elon Musk, who's not even an appointed official, certainly not nominated or senate confirmed as we normally expect for leadership of very senior roles. He's leading this, and it seems to be that he and these young guys are going directly into agencies getting access to writing code, to information being held by them, perhaps having their hand on different kinds of data and the ability to either allow that data to be public or to frame how individuals get their payments maybe from social security, whatever it might be. To me that seems like a kind of national heist and it's lawless in the sense that we as Americans who pay our tax dollars to these agencies literally have no idea what's going on inside them right now and that is actually quite frightening.

Justin Hendrix:

Yaël, how did we get here? We're in this extraordinary moment. You've been someone following these tech oligarchs closely for years, including at one point working inside of then Facebook. Elon Musk, another person that you've, it's right to say, come almost in direct conflict with in certain circumstances as well.

Yaël Eisenstat:

From that perspective – because the how did we get here question could be answered in many different ways. I'm not going to get into the history of how we got here in terms of the election outcome itself, but in terms of somewhat to David's point, right? If someone like an Elon Musk, being able to just enter these agencies, send his young little proteges or whoever they are in to do things like fire people, access our data, claim that they can rewrite code, all the things David mentioned. That's the point that I'm going to focus on here and I'll skip to the end and work backwards. I do think it's an amazing feat that people like Elon Musk have managed to convince a large portion, I don't think it's the majority, but a vocal portion of the United States that he cares about us and he cares about our democracy and the things he wants to do is to better serve us in free speech.

And that to me underpins how far we have let this information environment that completely spreads some of the most nonsensical narratives, and it just… I don't like to necessarily put it in terms of just mis and disinformation. This is pure propaganda. This is not just a question of everybody believing different things or we're all in our information bubbles for years. People like Elon Musk and now I think we can all agree, Mark Zuckerberg as well – I'm happy to get into that history there – have made it clear that they have their own political priorities with Musk. I believe it is somewhat ideological, but it is also about power and getting access to data that he can then do potential things with his vision of what is great for the future. With Mark Zuckerberg, I think it's purely about power. I don't think it's as ideological, but for years we have allowed these men to accumulate more and more power to control very large amounts of how people interact with each other, how they engage with information, how they view sources, what they're recommended for so long that the narratives now that many people would've not believed years ago, might've even laughed at has become more and more mainstream.

That is a point that is really important because the fact that Musk can completely break the law over and over again can do whatever he wants right now, unchecked in a very undemocratic way, and still be cheered on by very loud voices, shows that we have an information problem in general. Years ago when I left Facebook, I left in 2018, I wasn't there very long. I had been hired to head their elections integrity work for political ads, and when I left, I spoke up about nine months later about some of the real dangers and concerns I saw there. And I would get asked a lot by the press if I thought that Mark Zuckerberg put his finger on the scales of the 2016 election. And I would always say, that is the wrong question to ask. I will never be able to prove whether or not he put his fingers on the scale.

I don't know that there was even that kind of intention. The question you should be asking is how have we, as an open democratic society, allowed any one individual to have enough power that he could put his finger on the scales of the election if he wanted to. And I think that's what we've allowed with Elon Musk, and clearly, I again don't know if Zuckerberg intentionally put his finger on any scales. We all know that Elon Musk did, and I'm happy to go into details there, but that's where we find ourselves now, and it is absolutely terrifying for anyone who cares about true democracy, open society, accountability, transparency, all these things.

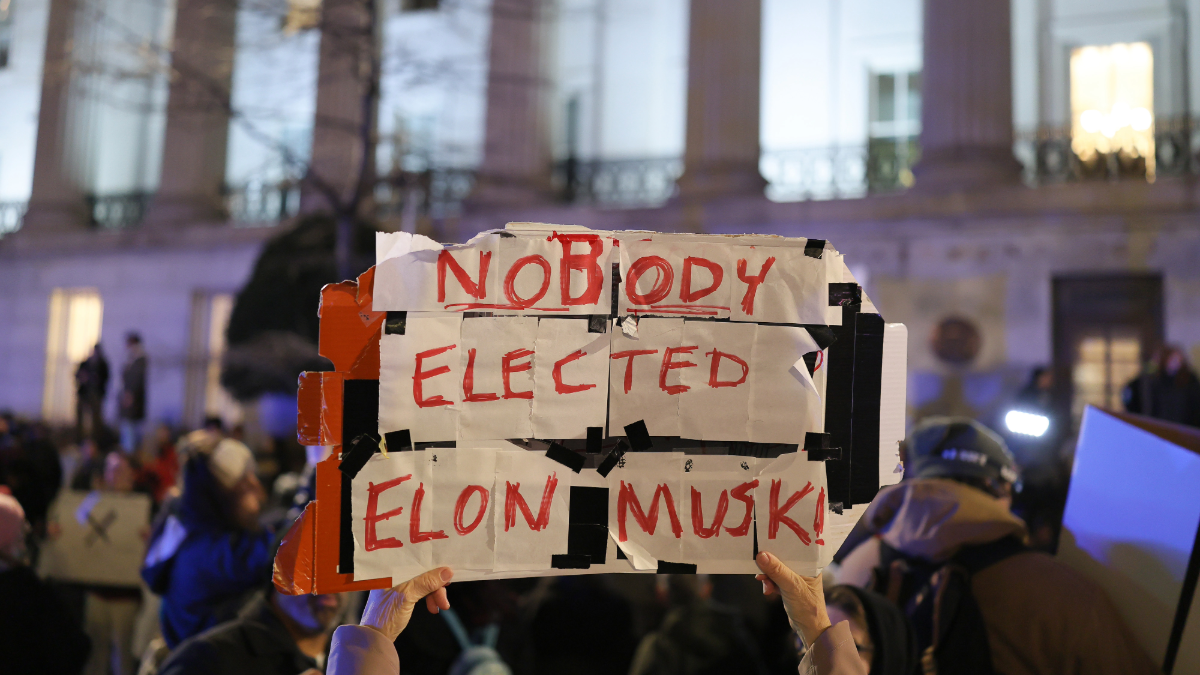

WASHINGTON, DC - FEBRUARY 04: A demonstrator holds up a sign during the We Choose To Fight: Nobody Elected Elon Rally at the US Department Of The Treasury. (Photo by Jemal Countess/Getty Images for MoveOn)

Justin Hendrix:

And so that goes beyond at this point, just putting your finger on the scale of knobs or buttons on a social media platform, we're also talking about money influence, which we've seen, of course, in Musk's case. David, you've looked at these issues around the world. How concerned are you fundamentally that the rule of law is in threat here? That we are in a constitutional crisis as some people seem to be arguing?

David Kaye:

I agree with everything that Yaël said, and I think you're asking the right question, how big of a threat is this? And I think it's enormous In some ways the comparisons that a lot of us are making to, for example, Hungary are insufficient for the moment. Let me start by saying one of the comparisons to Hungary is how quickly Viktor Orbán, when he came to power, essentially took control of mass media, of the judiciary of academics kicking out central European University essentially from Budapest, all of those things which were about the public square, the public space that Viktor Orbán controlled, but it actually took some time here. It's happening ridiculously quickly, to be honest. It's happening like a fire hose just over the last few weeks. Of course, we can go back over the last several months because as Yaël suggested, Elon Musk essentially used X as a propaganda arm for the Trump campaign.

I don't think there's much to dispute about that particular fact, but what we're seeing right now is on the one hand, a kind of threat to and takeover of public space. We see it in the context of harassment of the media harassment and attacks on academics, on universities, interference with academic freedom and the autonomy of universities. We see it in the context of harassment of civil servants in all of that kind of work. Then we see it also, if you read the executive orders, really it's punishing, but I encourage people to read some of these executive orders. I think they're like third-rate Orwellian trash. They're terribly written, but they are supercharged propaganda. So there's the attack on the media and all these other independent voices while at the same time there is this propaganda taking place and then on top of all of it, there's this total lack of transparency about what's happening within our governmental sector.

And then so there'll be lying about that too. All of these things together and on top of even beyond that, quiescence from the Republican side and a very slow move from the Democrats to recognize what's going on. All of those things put together make me really worried. I don't think we should all be alarmed. I don't think that means that we should think they won. I think there are a lot of lawsuits, Just Security is doing this fantastic litigation tracker that I think really highlights how much people are pushing back and there will be pushback, but I think it's all threat and very current, and it's very hard to know to my mind how this ends.

Justin Hendrix:

I agree with you on the executive orders, the one on K-12 indoctrination or ending indoctrination in schools literally reads like a kind of fascist screed. It's really on the nose in some ways.

David Kaye:

Yeah, completely. On the first day of the administration there was one that was, I think the title was Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Government Censorship. And it's a very short order, and of course, it's all projection, and this whole argument has been projection from the very beginning, which is all of social media is, on the one hand, all of social media is arrayed against conservative voices, which was always a ridiculous argument given that conservative voices had dominated downloads and so forth across and use these platforms. But at the same time, it's a direct response to this idea that the government was to use the word that a lot of the lawyers were using around jawboning, the government, putting pressure on platforms to take down, for example, public health disinformation or incitement to violence, things like that. The reality was very different, but that kind of co-opting of the free speech argument and the free speech ideal is a part of this both projection and also propaganda, and you see it, I think the one you mentioned is excellent as an example, but it's across all of the EOs.

Yaël Eisenstat:

The first EO, the one about free speech. I wasn't surprised because this narrative has been building, but I want to just pick up on two quick points that David said because I think they're really important for people to think about. One of course is this whole idea about we're reinstituting free speech. Let's just remember, and I will keep bringing up Elon Musk because to pretend that he and Trump are somehow separate and that Musk doesn't have an incredible influence in this is ridiculous at this point. Let's not forget that Elon Musk is a person who bought a platform in part because he wanted to silence his critics because he did not like how people were insulting him, who has tried to sue civil society organizations that have in any way exercised their own free speech. And David is a bigger expert, correct me if I'm saying any of this incorrectly, but when a civil society org is using their own First Amendment rights to say this is what we are seeing and this is how we view it, he is trying to sue those orgs out of oblivion while claiming to be the champion of free speech.

It's even interesting that this is a man who has helped proliferate potential doxxing lists of enemies within the government. After that, he goes and says, you cannot know who these 20-year-olds are that I am sending into government right now to try to access systems without even having security clearances. That would be doxxing. So it's free speech for me, but not for thee, and I just want to bring up one thing since you brought up jawboning it is amazing to me how much of this they claim was about how the government was jawboning companies like meta to take down information. I would argue the perfect definition of jawboning is when Donald Trump, the former president who was now campaigning to be the president again, threatens tech companies, claims he's going to jail. Someone like Mark Zuckerberg makes it very clear what he wants Mark Zuckerberg to do, otherwise, he's stripping him of his legal protections or potentially jailing him, and Mark Zuckerberg turns around and does exactly what Trump wanted him to do. That, to me, is a better example of jawboning than anything, and I just think that's important to recognize.

Justin Hendrix:

It's extraordinary to me to see some of the figures out of the kind of right-wing miasma around those types of claims around the Murthy v Missouri zone of argument. Essentially the weaponization committee that Jim Jordan's run, et cetera, some of those individuals appear to literally be seeing ideas that they seeded now carried out by Donald Trump. Characters like Mike Bins and others who were in that right-wing stew. Their ideas have been elevated and their actually being apparently it seems activated in a weird way. It almost feels like what we're experiencing is what it's like when the MAGA cinematic universe takes over. That's the operating system now.

David Kaye:

I think that's all correct. There's a way in which what we're seeing now should not be surprising to people who've been following this or paying attention for the last several years, really. And it goes back to, I mean it goes very far back, but the examples, there are just so many examples of this. I mean, there was the example of we might remember when Department of Homeland Security established this disinformation working group, and the right sort of took it as a censorship regime. This was going to be a mechanism to impose censorship when it was an effort to study the sort of foreign influence on our information space, which is not a bad thing for us to be studying, frankly, but they really amplified it as some Orwellian kind of effort when in fact they are adopting those kinds of strategies right now. And I think Yael is exactly right to highlight some of these other legal tactics that are being used in order to silence people.

And I think that is very much a part of it. It just goes beyond jawboning. It is just a fundamental effort to shape the information environment to shape what the public knows and what the public can say by attacking key participants in public space, whether that's trying to sue civil society organizations out of existence or, in fact, if you look at something like the shutdown of USAID Agency for International Development or the stop orders that have been imposed on State Department funding of organizations all around the world, it's a very similar kind of model of basically saying, we need to stop funding these, but the implication is that we need to ensure that critical information, including critical information of authoritarian allies of ours should not be spread around the world. Now, I don't think that was the fundamental purpose of those shutdowns or the shutdown of U-S-A-I-D, but that is a direct implication. So domestic and global, these things are part of a package

Yaël Eisenstat:

For years. One of the things I have worked on is the proliferation of conspiracy theories and extremism, whether it be online and yes also in the media, but why were so many of us so focused on this issue? Because the more that the companies were helping proliferate what used to be fringe, the more mainstream it's becoming, and now they're using those narratives to justify what they are doing. And an example when I knew the direction that this election was going to go and a lot of friends didn't love hearing it from me was when I started to see people I know not well, like people I went to college or high school with starting to post these interesting little takes, people who would never have been like MAGA Republicans were starting to post things that were very much straight out of some of the biggest conspiracy theorists mouths that were being perpetrated by Elon Musk.

And I saw people starting to parrot those talking points as something they were excited about and that's when I was like, wow, okay, so this is becoming more and more mainstream. People are actually excited about Elon Musk even if they're not necessarily excited about MAGA and this is why it's not about fact-checking what's false, what's right, what do I agree with, what do I disagree with? It is when you have these companies who, again, their interest is not about my safety or your safety, it is about their power. What they're trying to accomplish are actually contributing in spreading conspiracy theories and false narratives about what free speech even means it became mainstream. It doesn't mean that every, to be clear mainstream doesn't mean that everybody in America believes it, but it means that talking points that used to be much more on the fringe are becoming much more acceptable and now they are being used to ran z our democracy under this false guise of saving free speech and saving America from the censorship industrial complex. And that's just a really twisted perversion of this entire subject.

Justin Hendrix:

I can't get a read on how the quote-unquote public is reacting at the moment in my social media feed. Of course, people are horrified at the things that are going on, but I understand that's not the case. Of course, among many groups in the United States who are actually quite pleased to see something happening in Washington DC, something that they can essentially regard as movement in a capital that they regarded as too gummed up. There's a lot of distrust of institutions clearly underlying the enthusiasm for what's going on now. I dunno, how do you contend with that in your own mind? This was an election that was won, perhaps not in a landslide with a great mandate in the way that Republicans might like to frame it, but it was won decisively, and clearly, people want significant change.

David Kaye:

Look, I live in Los Angeles. I don't know that I have my finger on the pulse of the nation on this, but I do think that, or at least my sense or my guess is, that people aren't necessarily plugged into the implications of what's going on. And I've been thinking a little bit recently about a comparison. So before the October 7th attacks in Southern Israel across Israel, Israelis were out for almost a year every weekend protesting in the streets, shutting down highways, doing all of this, and what were they protesting over? They were protesting over a judicial reform law promoted by Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister. It was fairly arcane in certain ways. It was technical, but it brought people into the street in massive numbers. And I've been thinking about this because, over the last two weeks, we have not seen that in the United States, and even though I think what we're seeing in the US is far graver than merely one law about judicial reform, we're seeing that kind of assault on democracy, on steroids in the United States right now, and my sense is first of all, we're a very big country, so it's hard to do that.

What I think was missing or has been missing certainly over the last week, I think this should have started last weekend, was lawmakers actually creating a little bit of attention, creating a little bit of a scene kind of happening, going down to these agencies where these 20-year-old kids were basically getting access to all of this data going down to USAID where people were basically locked out of their systems without warning and basically saying, we are lawmakers. Congress has legislated and the president has enacted all of these laws that basically create this system of whether it's social security and our public welfare system or it's foreign assistance. Those are legalized entities that you can't just mess with without the rule of law. Now, maybe they deserve some reform, but this isn't the way to do it, and I think that without that kind of lawmaker action, I'd like to see some lawmakers get arrested, committing some civil disobedience, trying to get access because, without that, it's very hard to articulate to people. I think, what exactly are the implications of what's going on? We need to be doing that better ourselves. I think I'm even myself trying to think through how you articulate all of this stuff in a way that is very clear to the way people think about their own prosperity, their own participation in a democracy, and all that, but it's got to be boiled down. I don't think we're there yet. I don't think that's impossible for us to do, but I don't think we're there yet.

Justin Hendrix:

You mentioned the Just Security tracker. There are a lot of challenges to what Trump's doing. We've seen blocked in court some things, the birthright citizenship effort, some of the freeze on federal grants and loans, buyouts for federal workers still awaiting decision on some big stuff, including, as I understand it, the legality of Elon Musk's Department of Government efficiency. What happens if and when, and I thinking about the moment you just described that moment where people in Israel perhaps looked at it and said, wait a minute, the system's not functioning or we're in danger of the system, the constitutional order being broken here. What happens if the court rules one way or issues an injunction against Musk or some cabinet secretary who's seen through Musk's plans and they keep going?

David Kaye:

Yeah, that's a concern. It's a totally legitimate concern. Will they adhere to follow court orders? I don't know what will happen then. To be honest, I'm a little bit afraid, to be honest, and I don't want this to be all downer or even create a fear for people, but one of the things that I think the administration but also the right has done over the years is intimidate people to think that public protest might actually be dangerous for them. So there's surveillance, the possibility of surveillance, and the implications that might have for people's jobs, whether they're civil servants who still enjoy the right to protest, but if they're identified, are they going to lose their job? That's one thing, but the other is, let's be honest, Trump pardoned the January 6th insurrectionists, and these are people with guns, and so I'm really, I have this, I hardly even want to articulate it, but there's I think a concern among some people that public protest could turn to violence pretty quickly, and so I think those things combine. I don't know if that's a feature of the reluctance to protest. I think it isn't right now, but I think there is this lingering sense that there is danger in a way that there might not have been under other administrations that even during Black Lives Matter protests where people were concerned it was COVID so people were wearing masks. That kind of future, I think, is probably creating a little bit of a drag on public eagerness to be out there.

Justin Hendrix:

Yaël, I wanted to ask, you've been studying extremists and working to counter extremism in multiple roles that you've had in the past, that set of clemencies almost 1600 people, some of them convicted of violent crimes, some of them in prison for decades, for seditious conspiracy against the United States now free on the street being welcomed back into Trump rallies and around Capitol Hill. I don't know. How are you thinking about that? And I guess I'm asking that question from two dimensions. I guess they're reentry into the public's sphere, including on social media and in the broader public discourse, but also as David says, potentially on the streets as a kind of force that's there to see out Donald Trump's wishes.

Yaël Eisenstat:

They're reentry into society. I think it's bit too early to see exactly where that's going to lead. We've seen some already rearrested, I believe one was even killed in a traffic stop already. At the end of the day, even though it's hard to feel this right now, we do still have laws and people who freewheeling think they have the right to break the laws are likely to do it again and then I guess be arrested again. I don't know how that part plays out. Of course, it is concerning. It is concerning that not only have these guys been let out, but the message is you can act violently if that violence is because you are supporting the current president, and sure, that is concerning. I am hoping that is not, therefore, infiltrating the ideas that people have of whether or not there should be mass protests in the future.

I do think there's a lot of confusion about what mass protests look like. The Women's March was a huge march on the first day of Trump's first presidency, and now everyone's like, that didn't achieve anything, so why do that again? And I'm not giving an opinion either way. I'm just saying that's a big part of the mentality. You also asked about how other people are perceiving this. What's kind of interesting, though, is these guys also live in their own bubbles of information, right? Like David mentioned, he's in LA, I'm in New York. We follow who we follow. Do I know how every American is thinking about the current moment? Absolutely not. Do I assume that a vast majority of people are more tuned out than the three of us are? Absolutely. That said, there are things that are happening that are going to start affecting populations that are going to pay attention.

USAID is an interesting example. I served in government for years. I spent a few years overseas working hand in hand with USAID. A lot of my good friends are still working, I guess not, I guess now they're not as of what 5:00 PM today? The accusations that USAID is bloated or that they're a fake intel agency are, all those things have always existed. But what's interesting now, and I say interesting with heartbreak, it is heartbreaking to me to see what's happening to USAID, but the message that hasn't resonated enough, but will when it affects people, is how much US agriculture actually, how much of US farmers products are being sent to the countries where we are providing aid and how that is going to affect US farmers. Because that's the moment that I think will make a difference. I think when American pocket books are affected is when they will pay attention.

I wish they would've paid attention a lot earlier, but that's going to be some tipping points, right? Do I think it is dangerous in every way where we are right now? It's not just that Trump let all these people back on this street, Elon Muskie, all the people who had been kicked off the platform, not because people didn't like what they said, but because they violated extremism policies on the platform. He gave them all amnesty as well, like two years already. So we have set up an environment where a lot of these people are going to feel empowered. They're feeling empowered to joke about Nazi salutes. They're feeling empowered to threaten people. They're feeling empowered, especially to threaten transgendered people, to threaten people based on race, religion, identity, all these things, and that is a dangerous situation, but I still wonder when what they are doing truly affects people's pocketbooks if their will start to be a shift.

And I did see a poll, and I believe it was a YouGov poll. We usually poll the President's approval ratings, but they had polled Musk's approval ratings in November and then they redid it. I think just a week ago. I might have my days, not a hundred percent correct, but just recently and Musk's approval numbers are going down. Does that mean we're going to save what's happening in the next 24 48 hours? No, but I'm not sure it's accurate that so many people who voted for Trump are excited about the way these things are going down right now, and I think it's incumbent on all of us to make sure we are messaging this correctly. I think the more important message, unfortunately for America, is how American farmers are going to be affected by USAID closing down. I think the more important thing about the tariffs is making people understand how that would've affected them and how they are just ponds in this larger playbook by Trump or Musk or whoever.

Justin Hendrix:

I guess stepping back from this moment, which seems so urgent and seems like a crisis in the way that you all have described it, we've got this kind of confluence of right-wing populism. We could argue about how much that is about Donald Trump, how much that is a global phenomenon on some level, and then also extraordinary wealth inequality that's produced these oligarchs. Oxfam says, we're going to have multiple trillionaires stalking the planet within the next five years. Musk will be the first one, but also Zuckerberg, also, Bezos, also others, I don't know. What do you think that means for democracy and the ability of individuals to wade into even a government like the United States and essentially do as they wish, despite whatever laws might be on the books or whatever, checks and balances might be there to prevent them from pursuing their interests?

David Kaye:

Yeah, that's a big question, Justin. I think of it in a couple of different ways. The first way I think of it is purely backwards looking, and that is we missed our chance in a way. I think Lina Khan, for example, was fantastic and had this, as Tim Wu put it, this curse of bigness on her radar and I think made some efforts to address this issue of just enormous concentration of power in particular companies, not just big tech, but across industries. And I think she didn't get the kind of support from either the administration or from Congress that she really needed. And frankly, I'm not sure that the United States as a whole was ready to take the kind of action against those concentrations that we needed to take. And I think also that if we think about these not just as concentrations of wealth and concentrations of industry, I think it's also concentrations in the media space.

So whether it's social media or other kinds of media, one of the, I think, very disappointing things over the past few months, certainly in October, was the fact that Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong, the Washington Post and the LA Times owners, respectively, turned out not to be the great billionaire hopes that we had expected or hoped for. They both basically put the kibosh on endorsements for Kamala Harris and perhaps Bezos, a little bit less so than Soon-Shiong, who has really been wading into the opinion space. And I'm saying all this is, I don't want to get too much into the weeds, but this concentration of power is enormously problematic and destructive, not just of sort of individual policy. We could talk about government capture and all that, but it's really enormously destructive to our public square, to our ability to have conversations about issues. That to me is of real concern, and the idea of there being multiple trillionaires walking the planet is I think a signal of how much work we need to do to change that system and to recapture public space. There are efforts, there's, in the first Trump administration, there was a lot of, it was almost like a golden age of investigative journalism. Maybe we'll see some of that, but the pressure's going to be enormous.

Yaël Eisenstat:

This is part of going back to the thing I think I said in my very first answer, I used to always say the right question isn't being asked. The question is, why are we allowing people to be rich and powerful enough that they can have that much influence? Again, with Musk, I think it's very ideological. With Zuckerberg, I've always wondered how much money is enough money, how much power is enough power? I do wonder, and I'm wondering this in real-time, so it's not a perfectly thought out wonder here, but is there a point where it goes too far because in historical times, that's where revolution happened, and that's not going to necessarily be a great thing for us either. The most dangerous thing I see here is in addition to having such wealth and power, these very wealthy, powerful people also control all the ways that we communicate and engage with each other, receive information, and make sense of information.

And that is a really dangerous combination because it makes it much harder to explain to people why this is so dangerous and have them figure out how to react. Income inequality in itself is one of the biggest threats to a purely, truly functioning democracy, but what we're seeing now is so much more stark than in income inequality. It is more and more concentrated wealth in power in the hands of fewer and fewer individuals who have somehow convinced the world that's a gross overstatement, somehow convinced many Americans that they're fighting for them when nothing could be further from the truth. They're fighting to accumulate more wealth and power, and our biggest challenge is how to make that message really resonate with people because otherwise, it is very easy to feel hopeless in this moment. It is very easy to tune out in this moment. Apathy absolutely serves them, and so how to get these messages across without making people feel like there's nothing left they can do.

That's the real challenge. We are going to have to threaten this power system, and to be clear, being wealthy in and of itself is not a bad thing. I do think I'm going to criticize the left a little bit here too. I think the left focuses too much on rich people as bad, as opposed to talking about the concentration of wealth and power and how it's being used. I don't think being rich in and of itself is necessarily a bad thing, but it is about what are the checks and balances on everybody, and if they're not working against the wealthy, then they're not working to protect any of us.

David Kaye:

I agree with what Yaël said, but I don't think it's that rich people are bad. Billionaires are the problem. But you're right, and I do think the concentration of wealth, particularly if we're thinking in our world where we think a lot about social media, internet infrastructure, and all that, concentrations are going to be enormously destructive, and they've already undermined net neutrality. So the ability of different choke points to exist and really to cut off the spigot of freedom of information, I think is something that we need to be worried about, and that is a wealth issue.

Justin Hendrix:

Perhaps in our next conversation, we can talk more about that, also talk more about artificial intelligence and the extent to which that plays into that dynamic as well. It strikes me that a lot of these headlines about DOGE and about Musk seem to be about him gutting aspects of the federal government so that they can install some AI or apply some AI to either fix bits of the government or otherwise look for efficiencies, et cetera. I think there's going to be a lot more to say about all of these things, but David and Yaël, I appreciate you joining me today.

David Kaye:

Thanks for having me.

Yaël Eisenstat:

Thanks, Justin.

Authors