A Conspiracy Theory Goes to the Supreme Court: How Did Murthy v Missouri Get This Far?

Justin Hendrix, Ryan Goodman / Mar 17, 2024This piece is co-published with Just Security.

To be sure, there are important questions about the relationship between social media companies and the U.S. government, particularly when it comes to any governmental involvement in content moderation. Those questions should be addressed on a foundation of facts. The Supreme Court is instead about to address them on the basis of a concocted conspiracy theory.

On Monday, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Murthy v. Missouri, a case that requires the justices to consider whether the government coerced or “significantly encouraged” social media executives to remove disfavored speech in violation of the First Amendment.

While the legal questions presented are legitimate, a substantial amount of the underlying evidence now before the Court in this case is problematic or factually incorrect. Snippets of various communications between the government, social media executives, and other parties appear to be stitched together – nay, manufactured – more to support a culture war conspiracy theory than to create a credible factual record. How such claims made their way to the highest court is as worthy of consideration as the underlying legal questions on which the court must now rule.

Murthy v Missouri may become a landmark Supreme Court case in which the justices are led astray on the basis of a disinformation-laden record. The early signs are that some of the justices are already swept up in it.

Sorting fact from fiction

Murthy v Missouri started out as Missouri v Biden, a complaint filed with the US District Court for the Western District of Louisiana against President Joe Biden, several federal agencies, and government officials. On July 4, 2023, the district court granted a preliminary injunction, relying in significant part on a number of mischaracterizations and false claims in issuing a wide-ranging order limiting government communication with social media platforms and independent researchers.

The case eventually made its way to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which issued a modified injunction last October. But when the Supreme Court stayed the modified injunction later that month, Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas issued a dissent, referring to the District Court’s “extensive findings of fact” and stating that “the Court of Appeals agreed with the District Court’s assessment of the evidence, which, in its words, showed the existence of ‘a coordinated campaign’ of unprecedented ‘magnitude orchestrated by federal officials that jeopardized a fundamental aspect of American life.’”

Heading into the oral argument, it would appear that at least three justices believe the evidence presented of a conspiracy should be regarded as an accurate record (so much so that they would have upheld the injunction before even hearing argument).

Some conspiracies are, of course, true. But ample public reporting and filings in the case suggest this is hardly the case here. Here are a few examples:

1. Distortions/falsehoods about health officials’ statements

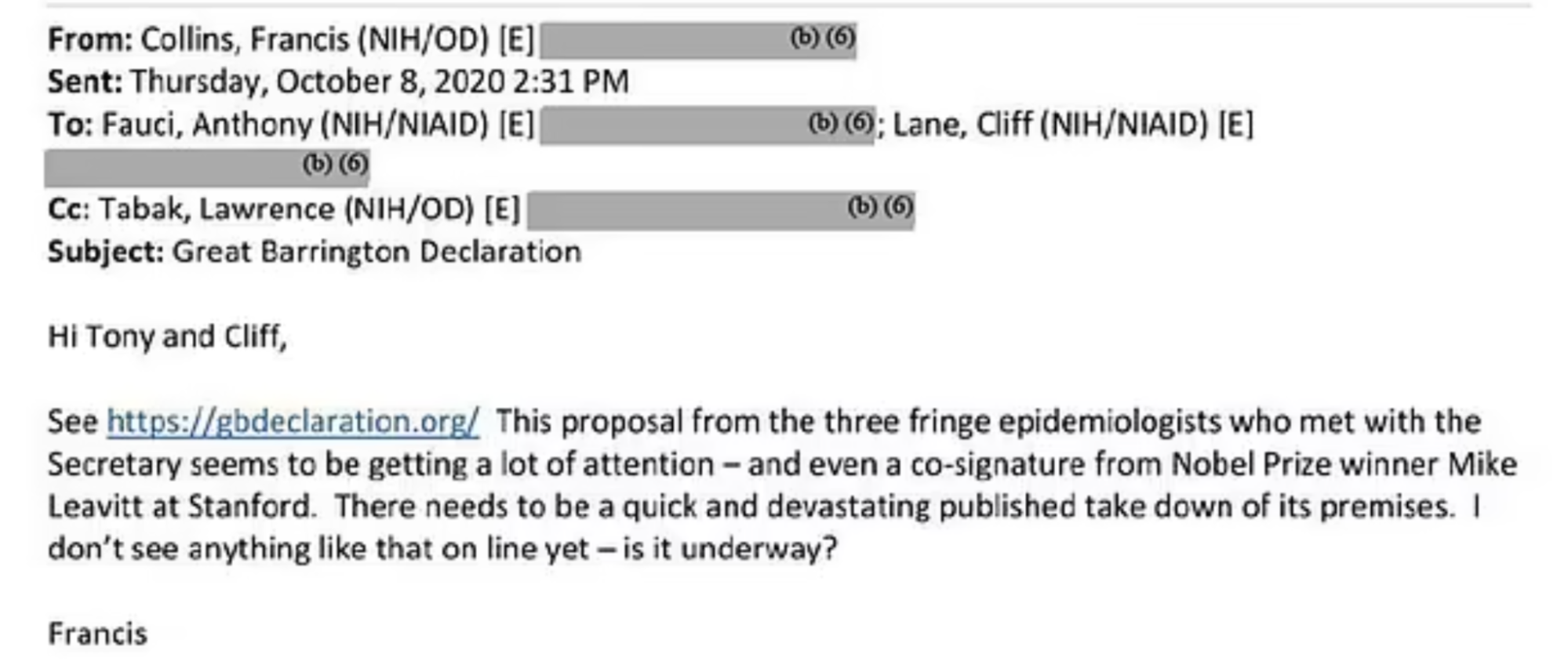

TechDirt’s Mike Masnick unpacked why claims in the district court about communications between Dr. Francis Collins, former director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, former chief media advisor to the President and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, were misleading at best.

Ripping facts out of context, the court took an email exchange by Dr. Collins to Dr. Fauci to mean that the two were plotting to have social media companies “take down” certain speech. The truth is the email exchange very clearly shows the two were discussing debunking it by publishing medical information (i.e., rebutting the speech with speech).

Judge Terry Doughty’s opinion:

“Various emails show Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits through evidence that the motivation of the NIAID Defendants was a ‘take down’ of protected free speech. Dr. Francis Collins, in an email to Dr. Fauci told Fauci there needed to be a “quick and devastating take down” of the GBD—the result was exactly that.”

Judge Doughty – outrageously – omitted the word “published” from the phrase “quick and devastating published take down” as well as the rest of the context. The actual email message:

Another example of problems in the record on health officials’ statements is presented in the Solicitor General’s reply in support of an application for a stay. The government notes that the respondents assert that “CDC officials requested and obtained ‘changes to the platforms’ moderation policies,’” but points out this “overlooks unrebutted testimony that ‘[CDC] did not discuss the development of [Facebook’s] policies, or the enforcement of their policies’ and instead merely provided ‘scientific information’ that Facebook ‘might use to do those things.’”

2. Distortions/falsehoods about FBI practices

The Solicitor General identifies “factual inaccuracies” in the record, including that the “[r]espondents claim that ‘in a single incident, the FBI pushed platforms to remove ‘929,000 tweets that were political speech by American citizens.’” Indeed, the district court also referred favorably to plaintiffs having, in the court’s view, “indicated that 929,000 tweets were political speech by American citizens.” But the Solicitor General notes the underlying document referenced makes clear the tweets referenced were actually sent by 422 accounts controlled by the Russian Internet Research Agency.

Former Twitter Trust & Safety head Yoel Roth, in an essay titled “Getting the Facts Straight,” detailed how the district court’s characterization of Twitter’s interactions with the FBI is not consistent with his own experience of the relationship. Roth notes that “[t]he Fifth Circuit asserts that the FBI’s interactions with platforms went beyond merely understanding what platform policies were, and extended to proactively shaping them,” but notes that “[c]laims in Missouri v. Biden that meetings with the government coerced platforms to change their rules don’t withstand scrutiny.”

3. Distortions/falsehoods about White House officials’ statements

The US Solicitor General, in a brief filed earlier this month, shows that many of the petitioners’ facts are flimsy or drawn from statements that are taken out of context. For instance, the district court gives the strong impression that then-White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki used the words “legal consequences” in purportedly threatening social media companies. The court wrote:

“At a White House Press Conference, Psaki publicly reminded Facebook and other social-media platforms of the threat of ‘legal consequences’ if they do not censor misinformation more aggressively.”

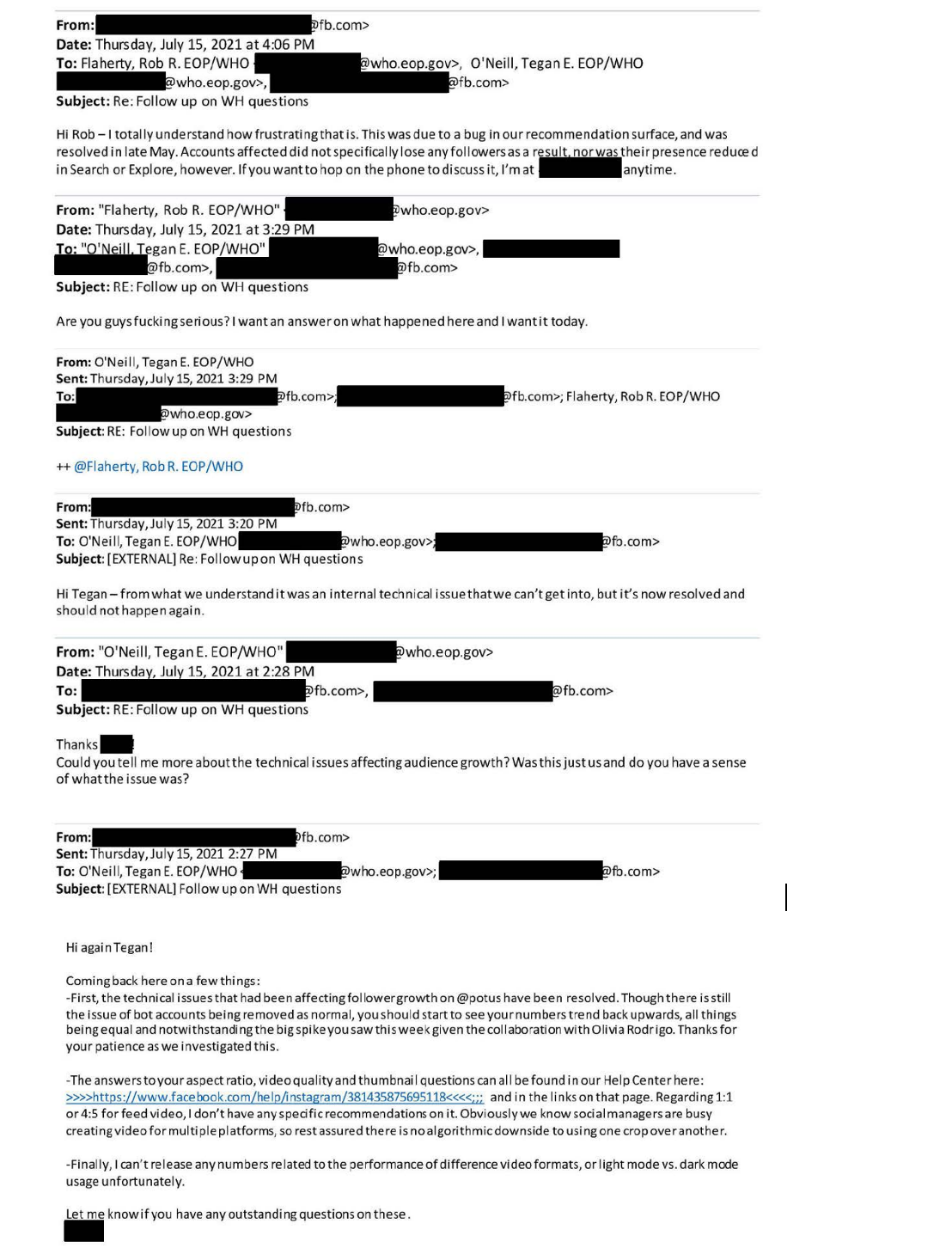

As the government points out “the Press Secretary never uttered the words ‘legal consequences’” (you can check the transcript). The government’s brief also points out that one of the more “supposedly ‘ominous and coercive’ ‘threats’” to Facebook from White House digital director Rob Flaherty in 2021 (‘Are you guys fucking serious? I want an answer on what happened here and I want it today.’) was in fact “asking for an answer about a ‘technical’ problem affecting the President’s own Instagram account—it had nothing to do with moderating other users’ content.”

Here is the email exchange:

For more on this, we recommend reading Dean Jackson, “First Amendment Defenders and the Supreme Court Should Reject the Jawboning Bogeyman,” Tech Policy Press, Feb. 22, 2024.

4. Distortions/falsehoods about academic researchers’ statements and practices

The district court engaged in such serious distortions of the facts involving academic researchers that it may explain why the Fifth Circuit omitted that part in its analysis and did not uphold the part of the injunction related to those actors. The fact that the Fifth Circuit could pass by such gross distortions and continue on without questioning the pattern of other similar distortions by the district court is a stain on the judicial system.

Stanford University, in its amicus brief to the Court, notes that “the Fifth Circuit did not accept any of the district court’s factual findings” related to projects its researchers were involved in, including the Election Integrity Partnership and the Virality Project. It goes on to detail why a number of the claims in the district court “were clearly erroneous when issued,” ranging from misquotations to outright fabrications. One of many such claims the brief rebuts is that posts by Jill Hines of an organization called Health Freedom Louisiana was “flagged” by the Virality Project. “There is no evidence—not in the record, not anywhere—that anyone involved with [the Virality Project] ever ‘flagged’ Jill Hines or Health Freedom Louisiana, ever shared any of their posts with a social media platform, or even read their posts,” the brief states. Another canard Stanford dispels relates to supposed statements by Renee DiResta, research manager at Stanford University (and a board member of Tech Policy Press). Stanford notes that four times in its opinion, the district court claims DiResta stated that “the EIP was designed to ‘get around unclear legal authorities, including very real First Amendment questions’ that would arise if CISA or other government agencies were to monitor and flag information for censorship on social media.” But, “the transcript that the district court cited to support its repeated misquotation contains no such language.”

Indeed. TechDirt’s Mike Masnick has an excellent analysis of how “[Judge] Doughty has put words in DiResta’s mouth” and “twists reality by viewing it through a distorted, conspiracy-laden prism.”

Facts are less interesting than ideas

The risk that Supreme Court justices may reason on the basis of such a problematic record is substantial. But it is also the case that many law experts moved quickly from any consideration of the true nature of the underlying communications between the government and the social media platforms to consider the more theoretical legal issues at play, including what constitutional tests might apply to determine if the government is engaged in inappropriate coercion or where new guidance from the Court might be useful. The sequence of events around Murthy v Missouri demonstrates that once a federal court has issued an opinion, it can force people to argue in certain circumstances as if the facts are true, and can incentivize legal experts to pivot to an intellectual plane of legal reasoning that is a step further removed from the actual facts.

In that way, the plaintiffs may have succeeded in significant part no matter how the Supreme Court ultimately rules, though a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs would boost a broader political and socio-cultural strategy. Murthy v Missouri has already managed to further equate content moderation – and government and researcher collaboration with platforms – with “censorship.” The case will be argued in an environment in which “misinformation about the First Amendment itself distorts policy debates and legislative interventions,” according to Dr. Mary Anne Franks, a First Amendment scholar at the George Washington University School of Law. And as Lisa MacPherson, a senior policy analyst at Public Knowledge points out, documents brought into the public domain over the course of two years of legal proceedings “have been the basis of hearings and angry letters from legislators making the discredited point that informed platform content moderation represents targeted suppression of conservative political viewpoints.”

In a contentious election year, there are signs this broader effort has succeeded in chilling coordination between platforms, government, civil society groups, and independent researchers on efforts to combat mis- and disinformation. Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, pointed out in an interview this week that information sharing between government agencies and platforms on threats such as foreign interference in elections has ground to a halt.

“In the past, we would share that information,” said Sen. Warner. “We are now in March 2024, months away from our next national election, and I feel we are less prepared today for the 2024 elections than we were at the corresponding time in the 2020 elections,” he said, situating the effects of this case amidst other factors, such as declining trust in elections in the United States, a retreat by social media companies on election integrity issues, and the uncertain effects of artificial intelligence on the information environment. That the Supreme Court may itself move forward in this case on the basis of flawed information should be of grave concern.

Authors