10 Years of Modi's Government: A Digital Policy Review

Amber Sinha / Nov 19, 2024

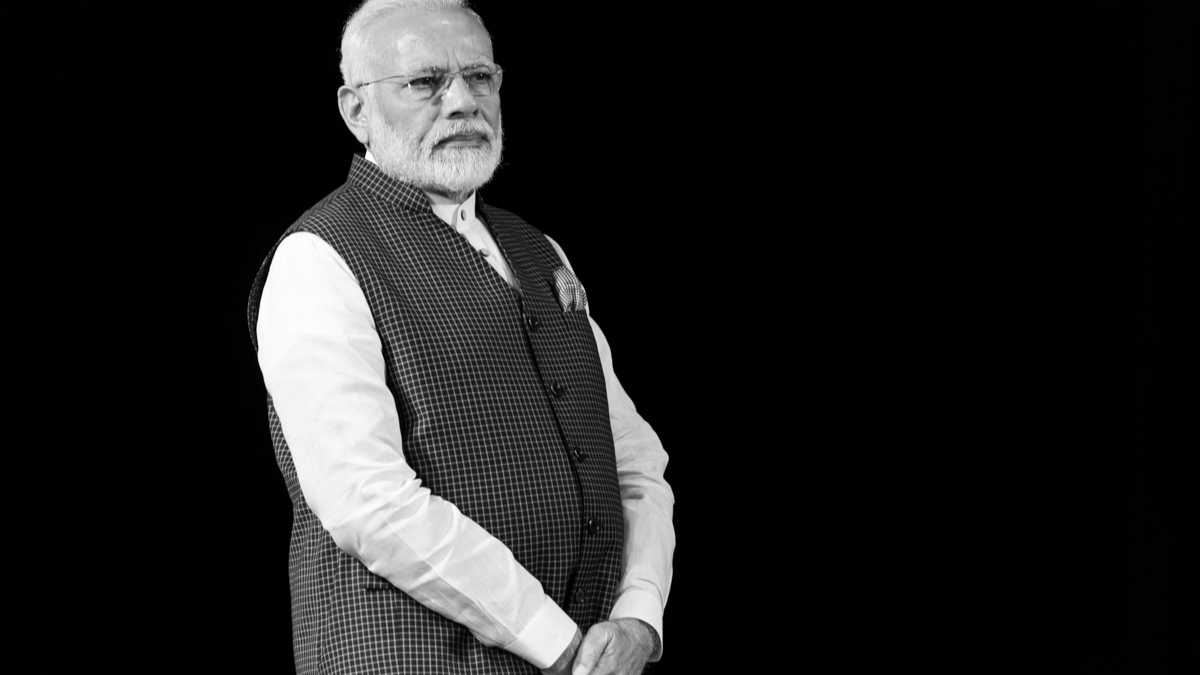

Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India is photographed backstage at a rally in his honor at NRG Stadium in Houston, Texas on Sunday, Sept. 22, 2019. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

Amber Sinha is a fellow at Tech Policy Press.

The Narendra Modi-led government came to power in India in 2014. Its first ten years in the government have coincided with digital policymaking occupying an increasingly central role in the story of the Indian nation. The number of Indians online and the many millions yet to access the Internet are important components of India’s current geopolitical positioning and potential global standing. Ten years and two national elections later, this provides an opportune time to review the Modi government’s decade of digital policymaking and its impact on digital rights and democracy.

The Pre-Modi Era: The Inherited Policies from the Singh Government

Before delving into the active policymaking steps taken by the Modi government, it is useful to take a quick look at what came before it, the policy and digital technology framework left behind by the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government. When Prime Minister Modi came to power in 2014, he inherited the foundations of the digital governance that would underpin his new government’s flagship program, Digital India. For instance, Aadhaar, the Unique Identity Project, originated in the National e-Governance Plan (NeGP) adopted by the preceding UPA Government.

In 2006, the NeGP was approved with the aim of extending the reach of government infrastructure and services to the remotest corners efficiently and at affordable costs. Initially, the NeGP focused on digitizing key government functions related to taxation, regulation of corporate entities, passport issuance, and pensions. Over time, it expanded to cover nearly all interactions between the state and citizens, from healthcare to education, transportation to employment, policing to housing. Once the central government launched Digital India, NeGP was subsumed under the new e-Gov and e-Kranti initiatives. A 2015 press release by the Central Government reporting on the approval of the Digital India program speaks of a ‘cradle to grave’ digital identity for all Indians.

Despite the BJP’s vocal opposition to the Aadhaar project while in the opposition, Modi’s government made it central to its plank of Digital India within months of coming to power. Today, Digital India includes dozens of Mission Mode Projects at various stages of implementation, all of which collect vast quantities of personally identifiable information. Moreover, they exist and prosper in a regulatory vacuum, given a lack of data protection legislation and minimal privacy policies. The preceding UPA government had flirted with two different drafts of privacy legislation in 2011 and 2014, neither of which advanced to law.

As such, Aadhaar’s legality has been a point of contention since 2012, with the project subject to legal challenges to different aspects of its data collection and processing, its exclusionary impacts, and the absence of an authorizing law that led to questions before the Supreme Court about whether the program violates the right to privacy. This litigation dominated digital policy discourse during the first phase of the Modi government.

Another key aspect of Modi’s internet law has faced legal scrutiny in the courts. Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, which held intermediaries accountable if they had actual knowledge of violations, was contested by a petition led by Shreya Singhal that argued the law chilled free speech. Within a year of Modi’s tenure, the court clarified that “actual knowledge” required that the government submit a judicial order to take down any content. This meant that rather than leaving it up to the wisdom of the intermediary to determine the illegality of third party content on their platforms, it now required judicial adjudication.

2015-17: Legal Battles, Privacy Concerns, and Strategic Shifts

After the launch of the Digital India program in 2014, the Modi government’s digital policy began to take shape, albeit under heavy public scrutiny. This early period saw the government still finding its feet as it navigated the digital policy environment, often on the defensive as it faced backlash from the media and civil society. The first notable development during this period was the Aadhaar litigation, which became a lightning rod for privacy.

In July 2015, the then Attorney General, Mukul Rohatgi, made a startling assertion in a hearing before the court, stating that there was no fundamental right to privacy. Relying on Supreme Court rulings from 1954 and 1963 (both cases decided by eight and six-judge majorities, respectively), he claimed that these precedents overruled subsequent judgments that upheld the right to privacy but by smaller majorities. It may have been one thing to argue the Aadhaar project was legal on the grounds that it was a reasonable restriction to the right to privacy, but quite another to claim that Indian citizens had no right to privacy at all, which the courts had assumed was settled law for decades.

At a practical level, Rohatgi’s tactic delayed the Aadhaar litigation by nearly three years, while the project continued largely unabated until it had become effectively ‘too big to fail.’ Strategically, it signaled the intent of the government to openly resort to legal technicalities to serve its immediate interests, with little consideration towards larger ramifications.

The Modi government’s next major initiative was the short-lived draft National Encryption Policy of 2015. This policy would have given the government control over encryption standards and threatened access to private communication, including enabling the government to prescribe encryption key sizes and algorithms. It was, in many ways, a continuation of government demands from the UPA government, where they sought blanket backdoor access to all communications data. It was also a response to the rise in end-to-end encryption, which could render such backdoors ineffective.

In response to widespread criticism, the Modi government withdrew the proposal within a week. Though the policy was shelved, the issue of encryption and government access to data would reappear in subsequent debates. 2015 also saw one of the rare, successful digital policy public campaigns in India on the issue of network neutrality. This was a campaign not so much geared not so much against the government but corporate players like Facebook and Airtel, and involved not MeitY, but the TRAI, India’s Telecom regulator. TRAI responded to the campaign and enacted regulations prohibiting online walled gardens.

In 2016, the government passed the Aadhaar Act as a spending bill, circumventing the authority of the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Parliament, where the BJP did not yet have a majority. To sidestep the upper house’s approval, the Modi government relied on creative legal drafting, partisan certification by the Speaker of the lower house, and the reluctance of the judiciary to adjudicate on the powers of the Speaker. It was the second time the Modi government undertook ‘extraordinary’ means and subverted the political process to achieve its contrived ends.

Despite this victory, the Aadhaar program remained mired in litigation. Eventually, in 2017, a nine-judge bench unanimously and emphatically upheld a fundamental right to privacy, delivering a public blow to the government’s effort to undermine privacy. The judgment also led to the setting up of a committee of experts to draft India’s data protection law.

This first phase, marked by continuous clashes with media, civil society, industry, and the judiciary, would signal the government’s approach during the next seven years. The government’s early missteps highlighted how mainstream the discourse of digital technology was becoming — and how unprepared the government was for public scrutiny of its policy efforts like Aadhaar. Losing the legal battle on privacy also caused the government to reorient its strategy to avoid putting itself in a position to suffer public legal defeats.

More importantly, the government seemed to have learned a valuable public relations lesson — avoid being cast as the malefactor. Instead, it began positioning other actors, particularly the foreign tech industry, as the villains in digital policy debates and the popular discourse.

2018-24: From Defensive Stances to Asserting Control over Data and Big Tech

In the latter half of the Modi government’s first decade in power, its approach to digital policy matured with a crystallization of objectives and more settled strategies to achieve them. By this stage, the government appeared better prepared for criticism of its policies, often deploying ready-made responses via well-aligned pro-government stakeholders in the public and private sectors. Across these six years, punctuated by two national elections, the Modi government would begin to assert its national vision and priorities for tech in the country through several key strategies. The political economy of actors, corporate and non-for-profit, local and foreign, also had more clearly defined interests and goals during this phase.

Ad-hoc engagements with Big Tech

Since the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2016, the Indian government has engaged in numerous ad hoc communications with major tech companies and platforms. In a 2018 speech in the Rajya Sabha, IT minister Ravi Shankar Prasad warned that social media platforms could not “evade their responsibility, accountability and larger commitment to ensure that their platforms were not misused on a large scale to spread incorrect facts projected as news are designed to instigate people to commit crime.”

Following revelations about Cambridge Analytica, MeitY sought details from both Cambridge Analytica and Facebook about how many Indian residents’ data was impacted during the incident. While Cambridge Analytica did not provide a clear response, Facebook admitted that the data of 560,000 Indians were compromised. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) was tasked with probing possible violations of the Information Technology Act, 2000, and the Indian Penal Code (IPC). While a threatening statement was issued by the ministry, the actual capacity of the government to take any legal action against Facebook or Cambridge Analytica was legally ambiguous, given the minimal data protection regulations in India.

Also, in 2018, the ministry engaged in a long and contentious public dialogue with WhatsApp over the spread of misinformation on the platform that may have played some role in a series of lynchings across the country. The IT Ministry sent notices to WhatsApp insisting, among other demands, that they build traceability of messages on the platform and warning that it will be liable and treated as “abettors” for crimes committed using the platform. WhatsApp consistently insisted that these demands would compromise the end-to-end encryption of the service. The ministry also made threats to shut down the service, though its legal authority to do so was questionable.

In 2021, the Modi government went after Twitter when MeiTY contended that the platform’s labeling of a BJP spokesperson’s tweet as ‘manipulated media’ would compromise an ongoing police investigation. Twitter’s labeling of the tweet seems to have been based on a fact-checking website whose investigation suggested that a part of the tweet appeared to be ‘manipulated.’ Despite legal provisions allowing the government to request content takedowns, there were no legal provisions under which it could seek the removal of a label like ‘manipulated media.’

The use of a police visit (a Special Cell of Delhi Police) to deliver notices at Twitter’s India headquarters continued a trend of visible, ad-hoc regulatory actions, often untempered by proportionality. This approach aligned with a global trend to target tech giants in high-profile conflicts to help bolster support for more restrictive government policies on speech.

Leaning into technological localization and protectionism

Over the last few years, the Modi government has sought to take advantage of growing narratives that Big Tech’s data-driven business models are inherently exploitative and extractive and part of a system of surveillance capitalism and, more recently, data colonialism. Within this context, India, like many countries, including Vietnam, Indonesia, and China, has pursued data localization policies, which Arindrajit Basu called the localization gambit. It is also an increasing view of emerging economies such as South Africa and Brazil, which consider the monetary benefits that American Big Tech companies gain as the product of unfair market advantages. Additionally, many governments and regulators have bristled at their failure to exercise reasonable law enforcement access to offshore data.

What began in April 2018 as the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) mandate for all companies to store payment system data within India soon ballooned into multiple other directives. The most significant data localization proposal was the mirroring requirement in the 2018 version of the data protection bill. The Personal Data Protection Bill released in August 2018 required that a live copy of all personal data be stored in India, along with a prohibition on cross-border data transfers for data classified as "critical personal data."

However, by the next year, when the updated draft was released, the mirroring requirements had been reduced significantly. This was in line with a similar flirtation with localization in Vietnam and Indonesia, which, too, was rolled back. Among the primary advocates for data localization were major domestic companies, such as Reliance and Phone Pe, which could establish data centers within the country or had the financial means to cover the costs of storing data in India. Other proponents were Chinese tech firms such as Alibaba, which had already established data centers in India. They viewed data localization as a chance to compete with Western companies that had yet to make similar investments. The final version of the data protection law moved to a ‘blacklisting’ approach, with sectoral regulators like the RBI having stricter regulations.

Tightening control over online content

After a series of ad-hoc engagements with online content companies whenever the government was especially displeased with specific content or the companies’ content regulation choices, a more structured response emerged in the form of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (IT Rules, 2021). The rules introduced a comprehensive regulatory apparatus for the governance of internet intermediaries, and online curated content and digital news.

The IT Rules, 2021 went against the spirit of the Shreya Singhal judgement in myriad ways. The language of the rules is often overbroad and vague, using terms that are not legal standards, leading to the possibility of a chilling effect. Further, intermediaries are given powers to remove content voluntarily, with impunity. To be in formal compliance with Shreya Singhal, the rules needed to ensure that intermediaries are only legally required to act on content takedown orders from authorized government agencies.

Earlier this year, the Modi government also tried to pass legislation circulated by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting seeking to bring over-the-top (OTT) services within the purview of broadcasting regulations. After much controversy, this draft legislation, the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill, was withdrawn in early October. Under the now-withdrawn bill, creators on platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and potentially TikTok, exceeding a certain number of users, would have been required to inform the Indian government of their activities and register under a three-tier regulatory system. This regulatory system was previously applicable to streaming platforms like Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, and Disney+ Hotstar.

During the most recent election in India, one of the most significant factors was the space provided by platforms like YouTube for alternative media sources and counter-narratives, including many journalists, formerly on traditional media, setting up channels on YouTube, as well as online-first influencers emerging in response to largely pliant and establishment-friendly print and television news media in India. Had the bill been enacted, these digital creators, particularly those critical of the government, would have faced significant regulatory hurdles.

Additionally, they would have had to establish a content evaluation committee at their own expense to review content before it was published. Any accounts that share news would also have had to comply with the notification requirements and follow the three-tier regulatory system, regardless of the size of their following. Finally, social media companies that did not share user information with the government could have faced criminal charges.

As much as the text of the withdrawn bill telegraphs the government’s intent to regulate online content creators in the future, its withdrawal is also an indication of the government’s shifting priorities.

Treating data as a national asset

In 2018, the Justice Srikrishna Committee Report, which accompanied the initial draft of the personal data protection bill, outlined a framework for collective privacy protection for identifiable communities that generate community data. While it didn’t provide specific recommendations, it emphasized the need for legislation that enables collective privacy protection through class action remedies or group sanctions. And though it focused on privacy protections, the report opened the conversation about treating data of collective groups together.

In 2019, the draft E-commerce policy expanded the concept of community data to be viewed as “societal commons” or a “national resource,” granting rights to access data sets to an unspecified ‘community,’ while the government retains ultimate control. The notion of 'data as a public good' was articulated in the 2018-19 Economic Survey Report, a document published by the Ministry of Finance along with the annual budget, pays lip service to privacy norms and the coming data protection law but makes no clear recommendations. Instead, it states that the 'personal data of an individual can be considered a public good when it is in government custody if the datasets are anonymized.’ It did not engage clearly with non-excludability and non-rivalry, economic prerequisites for an entity to be considered a public good, but instead contemplates private corporations to bid for data being held by the government.

The growing discourse around data as an asset coincided with the delays in enacting a data protection law. The delays can largely be attributed to a lack of political will. In recent times, there has been significant pressure from the judiciary as well as other actors, including voices from civil society, to create a strong law. At the same time, there has been greater recognition of privacy as a social and economic good. However, the series of data protection drafts from the Modi government set a poor example by equating the protection of privacy and personal data, which derives its origin from the positive right to privacy, with policy objectives influenced by political economy considerations such as ‘a free and fair digital economy’ (2018 draft), ‘interest and security of the state,’ and the need for ‘norms for social media intermediaries’ (2021 draft).

Aside from the data protection regulations, several other policy documents such as Niti Aayog’s National Strategy of Artificial Intelligence, the Ministry of Commerce’s Artificial Intelligence Task Force Report, and the Economic Survey of India 2018-19 echoed a growing national vision where data is at the center of the state’s welfare agenda, as well as its ambitions to compete in the AI race. Leveraging data for both welfare and innovation requires untangling the tricky matter of how personal data is differentiated from non-personal data, how we must deal with mixed datasets, and how to meaningfully obtain consent for these additional purposes.

There was a clear indication of intent by the Indian state to extract value from large datasets on Indian consumers maintained by corporations. By the early 2020s, the government coordinated various departments like MeiTy, the Ministry of External Affairs, and Niti Aayog for a unified pitch for Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), building on the earlier themes mentioned above. By the 2023 G20 held in India, DPI had become an approach of digital infrastructure, planning and innovation that the Modi government widely championed with support from local and international bodies like UNDP, World Bank, and Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The above policy goals are not only distinct from but may, in some cases, run contrary to the positive duty identified in the right to privacy — to protect Indian citizens from both state and private surveillance. While a comprehensive framework for Non-Personal Data (NPD), which was intended to facilitate the government’s interest in data, has not moved in the last few years, it underscores the government’s growing intent to control and harness data. This positioning may serve India’s geopolitical and economic ambitions but trades off upholding essential digital privacy rights.

What Lies Ahead: Modi Government’s Digital Policy at a Crossroads?

The recent withdrawal of the Broadcasting Bill was reminiscent of the quick demise of the encryption policy in the early years of the Modi administration, suggesting a setback on the digital policy front. Some observers see this as a sign of shifting political dynamics after a humbling result during the Lok Sabha elections in 2024, where the BJP could not muster up a majority on its own.

Yet, it would be premature to read too much into this. Despite the growing impact and awareness of tech policy, it still occupies a marginal position in the state’s mainstream agenda and the public imagination in India. As such, it is unclear whether the BJP’s coalition partners will force them to adopt a more consultative approach to such discussions, as they seem to have shown much more interest in federal funding for their states rather than a deep interest in the central government’s legislative agenda. It seems altogether unlikely that the issues on which the coalition partners chose to throw their weight will have anything to do with digital policymaking.

Moreover, as Apar Gupta has pointed out, MeiTY’s funding is minuscule compared to its mandate, and it is still led by ministers as their secondary portfolio after more plush ministries like Railways and Law and Justice. Thus, it is perhaps an indictment of the Modi Government’s limited imagination that a ministry that has both a broad and growing mandate and is expected to solve some of the most pressing and complex policy problems of this digital era remains deeply underresourced.

The author is grateful to Arindrajit Basu and Ben Lennett for their review and feedback.

Authors